Evaluating the Implementation of Raise the Age in New York City

Download the full report.

In April of 2017, Raise the Age legislation was signed into law, ending New York’s practice of automatically charging all 16- and 17-year-olds as adults for any offense. This was a significant piece of legislation that reinvested in the lives of young people across the state. This victory was won by a grassroots movement of youth, families, advocates, and lawyers, built across the state over more than a decade. The implementation of the new law was too important to leave unchecked and unexamined.

The Youth Justice Research Collaborative (YJRC)1 grew out of the Raise the Age movement. We came together to monitor the implementation of Raise the Age, documenting its successes and identifying areas for further reform. The YJRC was designed as a collective to center the lives and conditions of those most impacted, using participatory action research to join experts who have direct experience of youth prosecution and incarceration with a team of academics and advocates. The YJRC is a partnership of Youth Represent, the Public Science Project at the CUNY Graduate Center, Children’s Defense Fund-NY, the Citizens’ Committee for Children, and the many research associates who have contributed observation, analysis, and insight.

This brief report outlines our preliminary findings of Raise the Age’s first full year. It focuses principally on summarizing public data, but provides crucial and unique detail based on 473 court observations collected from June 1 to September 30, 2019 in New York City.2 Court watchers spent many hours a day, multiple times a week, across many months taking detailed and standardized notes of the proceedings (see “From the Court Watchers” to learn more).

In this report we begin by reviewing the youth arrest data, move to a look at youth detention, and conclude by comparing the newly created Youth Part of Adult Court with Family Court. In each of the sections we outline numbers that show signs of a successful implementation as well as areas of concern.

| Recommended citation: Youth Justice Research Collaborative, a partnership of the Public Science Project at the CUNY Graduate Center, Youth Represent, Children’s Defense Fund-NY, and the Citizens’ Committee for Children. (2020, August). Evaluating the Implementation of Raise the Age in New York City. Retrieved from https://opencuny.org/yjrc/reports-data/ |

Key Terms

- October 1, 2018: Raise the Age law applies to 16-year-olds

- October 1, 2019: Raise the Age law applies to 17-year-olds

- Adolescent Offender: A 16- or 17-year-old charged with a felony, whose case is first heard in the Youth Part of adult criminal court

- Youth Part: New part of adult criminal court where Adolescent Offenders have their case heard

- Removal/transfer: When the Youth Part judge decides to move an Adolescent Offender’s case from adult criminal court to Family Court

- Arraignment: First court appearance following arrest, where a person officially learns the charges against them, and a decision is made about whether they will be released or held in detention.

- Remand: When a person is held in jail without the option of paying bail.

- Bail: Amount set by a judge that a person must pay in order to be released from jail. In New York, bail may only be set for certain charges.

- Release on Recognizance / ROR: Release without bail or other conditions.

Youth Arrests: Significant Declines in Arrests, but Racial Disparity Persists

SUCCESSES:

Arrests of young people are the lowest they have been in several decades. Even before Raise the Age went into effect, arrests of youth under 18 had been dropping across New York State.

From 2010 to 2017, arrests of 16- and 17-year-olds decreased 54% in New York State.3

Arrests dropped even more sharply immediately after the law was passed, before it had even gone into effect, as stakeholders across systems responded to the policy goal of treating youth as youth.

Arrests of 16- and 17-year-olds in New York State dropped by 24% in a single year.4

In New York City, where our research study was focused, a similar arrest pattern emerged for both 16- and 17-year-olds.

During the first year of Raise the Age implementation in New York City, arrests among 16-year-olds decreased 41% from the prior year.5

Even arrests among 17-year-old New Yorkers decreased nearly 20% though the law didn’t yet apply to them.6

PERSISTENT PROBLEMS:

Over-Policing of Black and Latinx Youth Continues

While these are encouraging trends, there were still 2,522 arrests of 16-year-olds made in the first year of Raise the Age, almost half (46%) for misdemeanors or lesser charges. And while the number of arrests declined, racial disparity did not. Nearly all youth arrested in New York City were Black (61%) or Latinx (32%), and the vast majority were male (85%). Communities of color in New York City are still over-policed, a reality made overwhelmingly clear to a broader audience over weeks of Black Lives Matter protests in the wake of the murder of George Floyd at the hands of police in Minneapolis. In their homes, schools, and streets, 16- and 17-year-olds of color are exposed to ubiquitous police surveillance and frequent police contact in ways that, even if unrealized, make arrest a persistent possibility that only increases as they get older.

Youth Detention: More Young People Released but Too Many Still Detained

SUCCESSES:

Recognizing the harmful impact that detention and family separation have on young people, the Raise the Age law includes a presumption of release unless a judge identifies a reason to detain. In general, most young people charged as Adolescent Offenders (AOs) in the Youth Part of Adult Court were not detained in the first year of Raise the Age:

Eighty-one percent of the youth charged as AOs in New York City were released at arraignments.7

Seventy-six percent of New York City youth charged as AOs were released on their own recognizance (ROR), up from 60.1% for 16-yearolds during the year before Raise the Age went into effect.8 RORs increased whether youth were charged with violent or non-violent felonies.9

The data show the success of Raise the Age in driving down arrests and detention of youth under 18 to historically low levels. But our direct observations of Youth Parts and Family Courts also illustrate the problems with relying on criminalization and detention for youth, even at lower rates.

PERSISTENT PROBLEMS:

A Continued Reliance on Detention

About one in five (19%) of the young people charged as Adolescent Offenders (AOs) in the Youth Part of Adult Court were detained in the first year of Raise the Age and held at Crossroads Juvenile Center (Note: all 16-year-olds arrested and detained in Family Court were also sent to Crossroads).

The percent of AOs who were remanded or had bail set was 19%, down from 34% for 16-yearolds during the year prior Raise the Age went into effect.10

Of AOs who were detained, almost all (89%) were charged with violent felony offenses.11 In Family Court, 55% (237 of 432) of 16-year-olds charged as Juvenile Delinquents (JDs) under Raise the Age were detained.12

In contrast to AOs, only 7% of JDs detained in New York City were charged with violent felonies.13

Most youth detained as JDs in New York City were charged with misdemeanors and violations of probation.14

Detention Decisions Based on Charge Rather than Young Person’s Progress

Our court observations revealed a persistent reliance on detention for youth with more serious charges, especially in the Youth Part, even when strong evidence indicated the young person was doing well in the community and unlikely to re-offend. For example, one court observer noted:

The judge said that the 16 year old young Latinx woman had a stable home and a supportive family. Her mom was not available because she had to take an exam, but she really wanted to be there. The judge said that the young woman is participating in a program outside of Crossroads including family therapy and counseling and (sic) as well as work, and Summer Youth Employment Program. She goes to school—went to school every day prior to this and has goals to pursue college. She is self-aware and very thoughtful. She is a singer and songwriter. She is receiving great feedback from her teachers. Her art teacher says that she is very creative. Her English teacher says that she is a leader. She brought with her 22 certificates in total. The young woman does not dispute the seriousness of the matter. There are 2 other co-defendants and the 21 counts of the indictment do not apply to her. The court chooses to remand the young woman.

Detention Filling a Gap in Housing and Services

On the other hand, the court’s ability to support youth development outside of detention can be limited by the resources available. We also observed multiple cases where judges felt detention was the best of the available bad options. Here is a case observed in Family Court that illustrates this:

The young person had her head down on the table the whole time. I happened to sit next to the mother outside the court and overheard her mention she simply didn’t want the child to stay with her. When I walked into the courtroom, the judge had been scolding the City because they mentioned it wasn’t their policy to find youth housing. The judge said it was ridiculous that they would use that argument to fail the kid and that they need to find a way somehow. The judge was concerned because it seemed the only options were to remand her, which he was hesitant to do because he had no reason to, or have her be homeless.

Unnecessary detention is harmful to young people and represents a failure of the system and a distortion of the legislation. It places 16-year-olds in precarious environments for days, weeks, and even months, as NYC public data makes clear:

In New York City, the average length of time AOs were detained ranged from 3015 days to 39 days16 during the first year.17

In New York City, 16-year-old JDs were held in detention for shorter periods of time, with averages ranging from 5 days18 to 10 days19 during the first year.20

While detention has dropped since Raise the Age passed, there is more work to do investing in community supports for young people and families that keep youth out of detention, including education, stable housing, robust mental health options, employment opportunities, and income supports. These kinds of community-based investments also lay the groundwork for moving away from detention for children even for “serious” and “violent” offenses.

16-Year-Olds Arraigned in Adult Court

Under the Raise the Age law, 16-year-olds (as of October 1, 2018) and 17-year-olds (as of October 1, 2019) arrested and processed for felony charges are first arraigned in specialized youth courtrooms in adult court, called “Youth Parts.” From there, the case can be transferred to Family Court (also called “removal”) or can remain in the Youth Part. For 16-year-old New Yorkers, the vast majority were transferred to Family Court in the first year of Raise the Age.

In New York City, 1,137 16-year-olds were arrested and arraigned in Youth Parts of adult court in the first year of Raise the Age. 21

Of those arraigned, 84% had their cases transferred to Family Court. 93% of non-violent felony cases, and 80% of violent felony cases, were transferred to Family Court.22

Here is a typical example of the removal process observed in the Youth Part:

The people are consenting to removal.

The people say that they informed the victim of the possibility of removal and there was no objection. The DA says the complainant did not suffer significant physical injury. He says that the property was returned, there were no prior arrests. His mom, aunt, grandmother, and younger sister were present. The judge acknowledges this and says that it is very significant. The judge says that removing the case to the Family Court is a logical decision. The judge said he is very young and a felony conviction will stain his record.

16-Year-Olds in Family Court

Under Raise the Age, 16-year-olds charged with felonies whose cases are removed to Family Court are treated as Juvenile Delinquents (JDs), just like all 16-year-olds charged with misdemeanors. This means that they cannot be incarcerated in adult jails or prisons and that their cases are confidential and will not end with a public criminal record. We do not yet have enough data to say whether the overall outcomes for youth in Family Court are better than those in the adult system in terms of rates or length of detention, the burden of court mandated services and monitoring, and length of system involvement and supervision.

During the first year of Raise the Age, there were 433 JD petitions filed against 16-year-olds in New York City.23

Among all cases in New York City that were disposed during the first year where there was a finding of delinquency against the youth, 30% of felony-charged youth and 11% of misdemeanor-charged youth were subject to placement, meaning they were sent to a group home or state institution.24

Areas for Further Advocacy

Public data documenting the first year of Raise the Age implementation in Family Court and Youth Parts suggest positive trends in New York City. However, our observations still reveal three areas deserving further attention.

Dehumanizing Courtroom Environments:

The courtrooms we observed, in their routine practices and protocols, continue to feel like a dehumanizing and criminalizing environment not conducive to finding the most supportive outcomes for young people. The use of handcuffs and officers closely surrounding young people were two of the most concrete and quantifiable examples, and illustrate the difference between the Youth Parts and Family Court.

We observed that young people who transferred to Family Court under Raise the Age were less likely to be handcuffed and far less likely to be closely surrounded by court officers as compared to the Youth Part.

Our court observations in New York City revealed that 28% of cases in the Youth Part and 10% of cases in Family Court involved youth in handcuffs.

Almost three-fourths (73%) of the young people appearing before the judge in the Youth Part and nearly a quarter (24%) in Family Court were closely surrounded by at least one court officer.

In fact, multiple officers surrounded young people in the majority of Youth Part cases and a substantial number of cases in Family Court, as was frequently observed. One researcher noted,

“There are five court officers surrounding the defendant who looks like a child, given his short height and childlike face.”

The need for this close presence is questionable, based on our observations, given that officers are already posted in the courtroom. And while this presence is considerably less in Family Court, it is worth noting that under Raise the Age, any 16- or 17-year-old charged with a felony-level offense passes through the Youth Part before their case is moved to Family Court. When evaluating Raise the Age, it is necessary to account for this trajectory, remembering to consider the totality of the youth experience rather than any single court appearance.

The intimidating presence and behavior of court officers significantly impacts the whole courtroom, including family members and others who come to support young people. Shackling, including handcuffs, can inhibit a young person’s ability to engage in the court process. It can also be traumatizing and have a negative influence on the way others perceive them, and the way young people see themselves. 25 The spirit of Raise the Age legislation suggests the need to closely attend to the dehumanizing rituals and behaviors of the courtroom process.

The intimidating presence and behavior of court officers significantly impacts the whole courtroom, including family members and others who come to support young people. Shackling, including handcuffs, can inhibit a young person’s ability to engage in the court process. It can also be traumatizing and have a negative influence on the way others perceive them, and the way young people see themselves. 25 The spirit of Raise the Age legislation suggests the need to closely attend to the dehumanizing rituals and behaviors of the courtroom process.

Time and Substance Lost to the System

“I couldn’t help but feel my heart in my chest as the actors deliberated for nearly 15 minutes while the youth, handcuffed, waited and continuously put his head down.”

Waiting — lost time — was a prominent theme court observers frequently noted. Young people and their families must often endure significant time lost with multiple court dates, unreliable wait times, and unaccompanied sidebars where lawyers confer privately with the judge, out of earshot of the young person whose case is being heard. There is waiting on individual days, where youth and family must appear in court, and waits that occur over the course of a young person’s case, as decisions about where their case is heard, and its outcome, play out over days, weeks, and months. All of this waiting is exacerbated, and the stakes are higher, when a young person is detained.

The time from first appearance in the youth part to removal to Family Court averaged almost 10 days for AOs in New York City, ranging widely from an average 3 days in Brooklyn to 16 days in Queens.26

Citywide, 11% of the AO cases in New York City removed to Family Court took longer than a month.

Once in court, the waiting continues:

“Mom present for youth—mom showed up early in the morning (I saw her in the waiting area outside of courtroom around 10:30, 11am); patiently waited around until her son was called; he was the last case of the day, called around 3:23pm.”

Young people and their families wait in courtrooms for hours, sometimes all day – missing school and work – for their cases to be called, only for appearances to last just a few minutes.

In both the Youth Part and Family Court, over half of our observed appearances were under 10 minutes (69% and 62% respectively) and nearly a third lasted 5 or fewer minutes.

Young people, families, and friends watch as life-changing decisions are made about them in just a few minutes. For many reasons, the court experience often remains a dehumanizing experience. However, in these short appearances, judges and advocates sometimes attempt to see a more complete picture of the young person, beyond the act that brought them to the legal system.

Young people, families, and friends watch as life-changing decisions are made about them in just a few minutes. For many reasons, the court experience often remains a dehumanizing experience. However, in these short appearances, judges and advocates sometimes attempt to see a more complete picture of the young person, beyond the act that brought them to the legal system.

The Judge said, “Your report looks really promising and what I’m hearing sounds pretty good and like you’re heading in the right direction. There were a couple things here and there but we’ve discussed that…You’re doing pretty well where it matters most. Just keep working hard and going to your program. It sounds like you like reading. I’ve heard you’ve been reviewing some books in your English class. What types of things do you like to read?…Well that sounds great. Soon you’ll be able to put this behind you and be that great man that I know you are.”

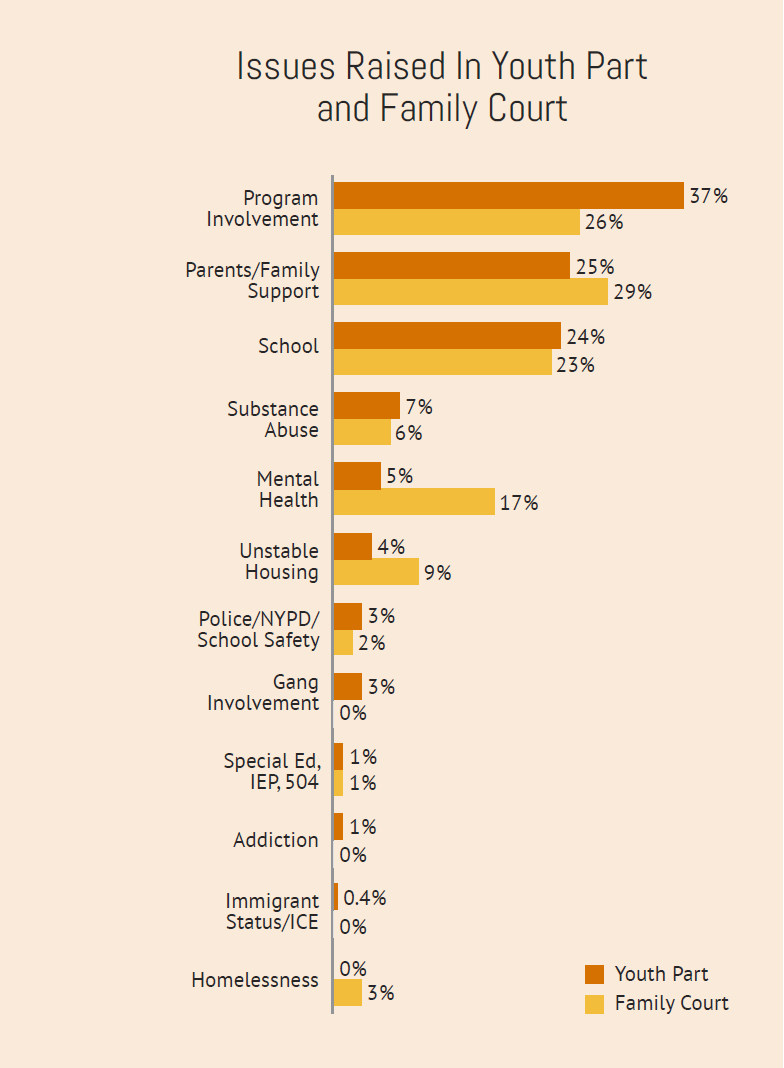

A full range of topics can be covered — fundamental issues like mental health, housing insecurity, and substance use — however, in both Youth Part and Family Court, program participation, school involvement, and parental support were discussed more than any other topic.

Evaluating the Raise the Age implementation is an opportunity to consider how more complete representations of young people are attended to and what impact it has on supporting the most beneficial outcomes.

Evaluating the Raise the Age implementation is an opportunity to consider how more complete representations of young people are attended to and what impact it has on supporting the most beneficial outcomes.

Centering Families:

The Raise the Age legislation provides a necessary reminder that we must center the young person’s interests. We also made countless observations prompting us to acknowledge that seldom are family experiences in the courtroom centered and explored. There is little attention to the impact of a young person’s court case on the rest of their family, including parents who may be caring for other children.

A few seconds after they went up to the bench, his mother walked in with a large family. She walked in with 5 of her children, including an older daughter who had her own baby in a stroller. It was amazing to see that this entire family showed up for the young person, especially because it was a workday that both mothers likely had to miss and because commuting to the courthouse with multiple young children — and a stroller — couldn’t have been easy. At the end, the mother stated to the judge that she’d be at his next appearance regardless of the date and time.

Indeed, parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, and other supporters are a significant presence and challenge the stereotype that families of the accused are negligent or uninvolved.

Parents or other family members were present in 56% of the Youth Part observations and 61% of the Family Court observations.

This could be an under-count since it often is hard to know for sure when family members are present. But the similar number across courtrooms underscores that this is about adolescents—as much in adult court as in family court—who have families that sacrifice a lot and care deeply about their children’s futures.

His father sighed and dropped his head in his hands and his grandfather looked confused as the court officers were leading his grandson away. The judge asked the father if he could make it on June 12th and the father said he’d have to take off of work but he’d make it. He was extremely polite to the judge and after the case ended, he thanked the judge and he comforted his son’s grandfather who was still trying to figure out what was going on.

Showing up to court often means missing work and school, finding childcare or bringing children, enduring emotional pain, among countless other challenges and barriers. At the same time, having a parent or other family member in court can impact the judge’s decision-making:

His mom, aunt, grandmother, and younger sister were present. The judge acknowledges this and says that it is very significant. The judge says that removing the case to the family court is a logical decision.

When evaluating the Raise the Age implementation, our observations strongly suggest the need to closely consider the courtroom experiences, treatment, barriers and impact of family members.

Extreme Racial Disparities Persist:

Our observations show how Black and Latinx youth continue to be disproportionately represented in the court system, despite Raise the Age reforms. Based on our observers’ perceptions of young people’s race/ethnicity, 88% of youth seen in Family Court and 95% of youth seen in the Youth Parts were young people of color. This is despite the fact that Black and Latinx youth represent only 22% and 36% of the City’s children, respectively.27 These findings are generally consistent with the state’s administrative data, which show that only 15% of 16-year-olds arrested on felony charges and 26% of 16-year-olds facing JD petitions in Family Court in New York City were white.28 In addition to being overrepresented in our courtrooms, Black and Latinx youth are more likely than their white peers to be detained. Over the course of the first year, 98% of all Adolescent Offenders and 96% of 16-year-old JDs admitted to detention were youth of color.29 While Raise the Age contributed to a shrinking youth justice system, our research on implementation must continue to confront and lift up the impacts of surveillance and over-policing of Black and Latinx communities, which bring young people to these courts.

Stay Tuned

The Youth Justice Research Collaborative (YJRC) is documenting the implementation of Raise the Age over two years and at multiple levels. Our goal is to share insights from our work and hold the policymakers and court actors accountable through collaborative research that bridges a broad set of expertise. This brief report focused just on 16-year-olds in the first full year of Raise the Age using pubic data and our 2019 – June through September – observations of Family Court and the Youth Parts of Adult Court.

Raise the Age was an important legislative victory that, now enacted, appears to be having a significant impact on the lives of young people and their families. The statistical trends from public data suggest the first year of this law led to fewer arrests, less detention, many transfers and a concerted effort to avoid criminalizing outcomes while offering beneficial resources and services. Still, young people, and most particularly Black and Latinx youth, continue to be exposed to pervasive police presence and contact that always threatens the possibility of arrest. Our systematic court observations of 473 cases suggested a need to attend more closely to the unnecessary reliance on detention, dehumanizing courtroom rituals, time lost to the system, and centering the sacrifice, experience and impact of the families whose support is critical to young people’s success.

Our court observations offer valuable depth to the breadth that public data provide. However, they represent only one method of a much larger participatory design. In 2019, while continuing court observations, we also advocated for a city-level Raise the Age data reporting bill. This year we launched a survey of public defenders, distributed a service provider survey and, in the coming months, will conduct in-depth interviews with youth and families to discuss their experiences.

As a research collective involved with a larger campaign, we are committed to communicating our results to multiple audiences using varying methods, including traditional reports as well as art and social-media. We hope our work will contribute to robust discourse about and strong advocacy for young people in New York City. We encourage you to stay tuned through our website (https://opencuny.org/yjrc/) and our social media activity (@YJRC_NYC) to follow all the future developments of our ongoing project.

YJRC thanks the foundations and individuals whose support made this work possible, including the New York Community Trust, the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the Tow Foundation, Trinity Church Wall Street, and the Prospect Hill Foundation.

Endnotes

1 The Youth Justice Research Collaborative is:

Cameron Bryan, Mica Baum-Tuccillo, Julia Davis, Elma Djokovic, Tianesha Drayton, Kadiata Kaba, Micaela Linder, Meryleen Mena, Britney Moreira, Karen Normil, Raymond Ortega, Alexander Perez, Kate Rubin, Adilene Sierra, Brett Stoudt, Maya Tellman, and Maya Williams. Youth Justice Research Collaborative alumni include: Zann Balosun-Simms, Dagny Blackburn, Keybo Carrillo, Kat Diab, Latune Finch, Nora Howe, Fa-tu Kamara, Jaizyha Jones, Khadijah Jones, Elena Lufty, Lauren Miller, Elizabeth Valldejuli, Dale Ventura, and Max Selver.

2 Court observations were made in Family Court (191 observations), and in the Youth Parts of Supreme Court (282 observations) in Brooklyn, the Bronx, Manhattan and Queens.

3 New York State Raise the Age Implementation Task Force Report, First Annual Report (Aug. 2019) p. 8-9, available at: https://www.ny.gov/sites/ny.gov/files/atoms/files/NYS_RTA_Task_Force_First_Report.pdf.

4 There were 6,289 arrests of 16- and 17-year-olds from January–June 2017 and 4,796 arrests of 16- and 17-year-olds from January – June 2018. Raise the Age went into effect for 16-year-olds on October 1, 2018 and for 17-year-olds on October 1, 2019. See New York State Arrests (Fingerprintable) Involving 16-17 Year Olds January-June, 2017 – 2019, available at: https://www.criminaljustice.ny.gov/crimnet/ojsa/NYS%20RTA%20Arrests%20YTD.pdf.

5 New York City Criminal Justice Agency, The First Year of Raise the Age, May 2020, at 2, available at: https://www.nycja.org/publications/the-first-year-of-raise-the-age.

6 Id.

7 New York City Criminal Justice Agency, The First Year of Raise the Age, May 2020, at 2, available at: https://www.nycja.org/publications/the-first-year-of-raise-the-age.

8 Id.

9 Id.

10 New York City Criminal Justice Agency, The First Year of Raise the Age, May 2020, at 21, available at: https://www.nycja.org/publications/the-first-year-of-raise-the-age.

11 New York State Raise the Age Implementation Task Force, Raise the Age Impact by the Numbers (Oct. 1, 2018 through Sept. 30, 2019), at 19, available at: https://www.criminaljustice.ny.gov/crimnet/First_Year_Data.pdf.

12 Id. at 7 & 9. Note that this data represents petitions and admissions, not unique young people.

13 This is not the case outside of NYC, where that was true for only 60% of AOs in detention. New York State Raise the Age Implementation Task Force, Raise the Age Impact by the Numbers (Oct. 1, 2018 through Sept. 30, 2019), at 21, available at: https://www.criminaljustice.ny.gov/crimnet/First_Year_Data.pdf.

14 Id.; RTA Implementation Task Force Report, p. 57.

15 New York State Office of Children and Family Services, Q3 Juvenile Justice Detention Monitoring Report (7/1/2019-9/30/2019 – https://ocfs.ny.gov/reports/detention/monitoring/Detention-Monitoring-Report-2019-Q3.pdf).

16 New York State Office of Children and Family Services, Q2 Juvenile Justice Detention Monitoring Report (4/1/2019-6/30/2019 – https://ocfs.ny.gov/reports/detention/monitoring/Detention-Monitoring-Report-2019-Q2.pdf).

17 New York State Office of Children and Family Services, Q1 Juvenile Justice Detention Monitoring Report (1/1/2019-3/31/2019 – https://ocfs.ny.gov/reports/detention/monitoring/Detention-Monitoring-Report-2019-Q1.pdf).

18 New York State Office of Children and Family Services, Q3 Juvenile Justice Detention Monitoring Report (7/1/2019-9/30/2019 – https://ocfs.ny.gov/reports/detention/monitoring/Detention-Monitoring-Report-2019-Q3.pdf).

19 New York State Office of Children and Family Services, Q2 Juvenile Justice Detention Monitoring Report (4/1/2019-6/30/2019 – https://ocfs.ny.gov/reports/detention/monitoring/Detention-Monitoring-Report-2019-Q2.pdf).

20 The data contained here reflects information reported for January 1, 2019-September 30, 2019, which is three-quarters of the first year of implementation.

21 New York State Raise the Age Implementation Task Force, Raise the Age Impact by the Numbers (Oct. 1, 2018 through Sept. 30, 2019, at 3, available at: https://www.criminaljustice.ny.gov/crimnet/First_Year_Data.pdf.

22 Id. at 2.

23 New York State Raise the Age Implementation Task Force, Raise the Age Impact by the Numbers (Oct. 1, 2018 through Sept. 30, 2019), at 6, available at: https://www.criminaljustice.ny.gov/crimnet/First_Year_Data.pdf.

24 Id. at 7. In raw numbers there were a total of 101 JD findings in felony petitions and 30 young people subject to placement; and a total of 37 misdemeanor JD findings and 4 young people subject to placement.

25 National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges, Resolution Regarding Shackling of Children in Juvenile Court, available at: https://njdc.info/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/NCJFCJ_Resolution-Regarding-Shackling-of-Children-in-Juvenile-Court.pdf.

26 New York City Criminal Justice Agency, The First Year of Raise the Age, May 2020, at 28, available at: https://www.nycja.org/publications/the-first-year-of-raise-the-age.

27 CCC analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates, Public Use Microdata Sample File (2005-2018); retrieved from https://data.census.gov/, available at: https://data.cccnewyork.org/data/table/98/child-population#11/18/40/a/a.

28 New York State Raise the Age Implementation Task Force, Raise the Age Impact by the Numbers (Oct. 1, 2018 through Sept. 30, 2019, at 6, available at: https://www.criminaljustice.ny.gov/crimnet/First_Year_Data.pdf.

29 Id.

Graphic design: Savanna Honerkamp-Smith | 2020