The Water Cure

The Water Cure

Debating torture and counterinsurgency-a century ago.

by Paul Kramer February 25, 2008

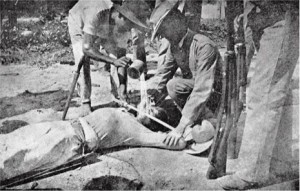

A picture of a “water detail,” reportedly taken in May, 1901, in Sual, the Philippines. “It is a terrible torture,” one soldier wrote

Many Americans were puzzled by the news, in 1902, that United States soldiers were torturing Filipinos with water. The United States, throughout its emergence as a world power, had spoken the language of liberation, rescue, and freedom. This was the language that, when coupled with expanding military and commercial ambitions, had helped launch two very different wars. The first had been in 1898, against Spain, whose remaining empire was crumbling in the face of popular revolts in two of its colonies, Cuba and the Philippines. The brief campaign was pitched to the American public in terms of freedom and national honor (the U.S.S. Maine had blown up mysteriously in Havana Harbor), rather than of sugar and naval bases, and resulted in a formally independent Cuba.

The Americans were not done liberating. Rising trade in East Asia suggested to imperialists that the Philippines, Spain’s largest colony, might serve as an effective “stepping stone” to China’s markets. U.S. naval plans included provisions for an attack on the Spanish Navy in the event of war, and led to a decisive victory against the Spanish fleet at Manila Bay in May, 1898. Shortly afterward, Commodore George Dewey returned the exiled Filipino revolutionary Emilio Aguinaldo to the islands. Aguinaldo defeated Spanish forces on land, declared the Philippines independent in June, and organized a government led by the Philippine élite.

During the next half year, it became clear that American and Filipino visions for the islands’ future were at odds. U.S. forces seized Manila from Spain-keeping the army of their ostensible ally Aguinaldo from entering the city-and President William McKinley refused to recognize Filipino claims to independence, pushing his negotiators to demand that Spain cede sovereignty over the islands to the United States, while talking about Filipinos’ need for “benevolent assimilation.” Aguinaldo and some of his advisers, who had been inspired by the United States as a model republic and had greeted its soldiers as liberators, became increasingly suspicious of American motivations. When, after a period of mounting tensions, a U.S. sentry fired on Filipino soldiers outside Manila in February, 1899, the second war erupted, just days before the Senate ratified a treaty with Spain securing American sovereignty over the islands in exchange for twenty million dollars. In the next three years, U.S. troops waged a war to “free” the islands’ population from the regime that Aguinaldo had established. The conflict cost the lives of hundreds of thousands of Filipinos and about four thousand U.S. soldiers.

Within the first year of the war, news of atrocities by U.S. forces-the torching of villages, the killing of prisoners-began to appear in American newspapers. Although the U.S. military censored outgoing cables, stories crossed the Pacific through the mail, which wasn’t censored. Soldiers, in their letters home, wrote about extreme violence against Filipinos, alongside complaints about the weather, the food, and their officers; and some of these letters were published in home-town newspapers. A letter by A. F. Miller, of the 32nd Volunteer Infantry Regiment, published in the Omaha World-Herald in May, 1900, told of how Miller’s unit uncovered hidden weapons by subjecting a prisoner to what he and others called the “water cure.” “Now, this is the way we give them the water cure,” he explained. “Lay them on their backs, a man standing on each hand and each foot, then put a round stick in the mouth and pour a pail of water in the mouth and nose, and if they don’t give up pour in another pail. They swell up like toads. I’ll tell you it is a terrible torture.”

On occasion, someone-a local antiwar activist, one suspects-forwarded these clippings to centers of anti-imperialist publishing in the Northeast. But the war’s critics were at first hesitant to do much with them: they were hard to substantiate, and they would, it was felt, subject the publishers to charges of anti-Americanism. This was especially true as the politics of imperialism became entangled in the 1900 Presidential campaign. As the Democratic candidate, William Jennings Bryan, clashed with the Republican incumbent over imperialism, which the Democrats called “the paramount issue,” critics of the war had to defend themselves against accusations of having treasonously inspired the insurgency, prolonged the conflict, and betrayed American soldiers. But, after McKinley won a second term, the critics may have felt that they had little to lose.

Ultimately, outraged dissenters-chief among them the relentless Philadelphia-based reformer Herbert Welsh-forced the question of U.S. atrocities into the light. Welsh, who was descended from a wealthy merchant family, might have seemed an unlikely investigator of military abuse at the edge of empire. His main antagonists had previously been Philadelphia’s party bosses, whose sordid machinations were extensively reported in Welsh’s earnest upstart weekly, City and State. Yet he had also been a founder of the “Indian rights” movement, which attempted to curtail white violence and fraud while pursuing Native American “civilization” through Christianity, U.S. citizenship, and individual land tenure. An expansive concern with bloodshed and corruption at the nation’s periphery is perhaps what drew Welsh’s imagination from the Dakotas to Southeast Asia. He had initially been skeptical of reports of misconduct by U.S. troops. But by late 1901, faced with what he considered “overwhelming” proof, Welsh emerged as a single-minded campaigner for the exposure and punishment of atrocities, running an idiosyncratic investigation out of his Philadelphia offices. As one who “professes to believe in the gospel of Christ,” he declared, he felt obliged to condemn “the cruelties and barbarities which have been perpetrated under our flag in the Philippines.” Only the vigorous pursuit of justice could restore “the credit of the American nation in the eyes of the civilized world.” By early 1902, three assistants to Welsh were chasing down returning soldiers for their testimony, and Philippine “cruelties” began to crowd Philadelphia’s party bosses from the pages of City and State.

At about the same time, Senator George Frisbie Hoar, of Massachusetts, an eloquent speaker and one of the few Republican opponents of the war, was persuaded by “letters in large numbers” from soldiers to call for a special investigation. He proposed the formation of an independent committee, but Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, another Massachusetts Republican, insisted that the hearings take place inside his own, majority-Republican Committee on the Philippines. The investigation began at the end of January, 1902, and, in the months that followed, two distinct visions of the hearings emerged. Hoar had hoped for a broad examination of the conduct of the war; Lodge, along with the Republican majority, wanted to keep the focus on the present, and was “not convinced” of the need to delve into “some of the disputed questions of the past.” For the next ten weeks, prominent military and civilian officials expounded on the progress of American arms, the illegitimacy of Aguinaldo’s government, its victimization of Filipinos, and the population’s incapacity for self-government and hunger for American tutelage.

Still, the subject of what was called, with a late-Victorian delicacy, “cruelties” by U.S. troops arose a few days into the hearings, at the outset of three weeks’ testimony by William Howard Taft. A Republican judge from Ohio, Taft had been sent to the islands to head the Philippine Commission, the core of the still prospective “postwar” government. He was speaking about the Federal Party, an élite body of collaborating Filipinos who were aiding “pacification,” when Senator Thomas Patterson, a Democrat from Colorado, abruptly inquired about “the use of the so-called water cure in securing the surrender of guns.” Taft replied that he “had intended to speak of the charges of torture which were made from time to time.” He then allowed himself to be redirected by the young Indiana senator Albert Beveridge, an ardent imperialist who wanted to discuss the deportation of Filipino “irreconcilables” to Guam. But antiwar senators proved persistent. Minutes later, Senator Charles A. Culberson, a Democrat from Texas, pushed again. This time, Taft conceded:

That cruelties have been inflicted; that people have been shot when they ought not to have been; that there have been in individual instances of water cure, that torture which I believe involves pouring water down the throat so that the man swells and gets the impression that he is going to be suffocated and then tells what he knows, which was a frequent treatment under the Spaniards, I am told-all these things are true.

Taft then immediately tried to contain the moral and political implications of the admission. Military officers had repeatedly issued statements condemning “such methods,” he claimed, backing up their warnings with investigations and courts-martial. He also pointed to “some rather amusing instances” in which, he maintained, Filipinos had invited torture. Eager to share intelligence with the Americans, but needing a plausible cover, these Filipinos, in Taft’s recounting, had presented themselves and “said they would not say anything until they were tortured.” In many cases, it appeared, American forces had been only too happy to oblige them.

Less than two weeks later, on February 17, 1902, the Administration delivered to the Lodge committee a fervent response that was tonally at odds with Taft’s jocular testimony. Submitted by Secretary of War Elihu Root, the report proclaimed that “charges in the public press of cruelty and oppression exercised by our soldiers towards natives of the Philippines” had been either “unfounded or grossly exaggerated.” The document, entitled “Charges of Cruelty, Etc., to the Natives of the Philippines,” was an unsubtle exercise in the politics of proportion. A meagre forty-four pages related to allegations of torture and abuse of Filipinos by U.S. soldiers; almost four hundred pages were devoted to records of military tribunals convened to try Filipinos for “cruelties” against their countrymen. If the committee sought atrocities, Root suggested, it need look no further than the Filipino insurgency, which had been “conducted with the barbarous cruelty common among uncivilized races.” The relatively slender ledger of courts-martial was not, for Root, evidence of the unevenness of U.S. military justice on the islands. Rather, it showed that the American campaign had been carried out “with scrupulous regard for the rules of civilized warfare, with careful and genuine consideration for the prisoner and the noncombatant, with self-restraint, and with humanity never surpassed, if ever equaled, in any conflict, worthy only of praise, and reflecting credit on the American people.”

The scale of abuses in the Philippines remains unknowable, but, as early as March, rhetoric like Root’s was being undercut by further revelations from the islands. When Major Littleton Waller, of the Marines, appeared before a court-martial in Manila that month, unprecedented public attention fell on the brutal extremities of U.S. combat, specifically on the island of Samar in late 1901. In the wake of a surprise attack by Filipino revolutionaries on American troops in the town of Balangiga, which had killed forty-eight of seventy-four members of an American Army company, Waller and his forces were deployed on a search-and-destroy mission across the island. During an ill-fated march into the island’s uncharted interior, Waller had become lost, feverish, and paranoid. Believing that Filipino guides and carriers in the service of his marines were guilty of treachery, he ordered eleven of them summarily shot. During his court-martial, Waller testified that he had been under orders from the volatile, aging Brigadier General Jacob Smith (“Hell-Roaring Jake,” to his comrades) to transform the island into a “howling wilderness,” to “kill and burn” to the greatest degree possible-“The more you kill and burn, the better it will please me”-and to shoot anyone “capable of bearing arms.” According to Waller, when he asked Smith what this last stipulation meant in practical terms, Smith had clarified that he thought that ten-year-old Filipino boys were capable of bearing arms. (In light of those orders, Waller was acquitted.)

The disclosures stirred indignation in the United States but also prompted rousing defenses. Smith was court-martialled that spring, and was found guilty of “conduct to the prejudice of good order and military discipline.” Yet the penalty was slight: he was simply reprimanded and made to retire early. Root then used the opportunity to tout the restraint that the U.S. forces had shown, given their “desperate struggle” against “a cruel and savage foe.” The Lodge committee, meanwhile, maintained its equanimity, with a steady procession of generals and officials recounting the success and benevolence of American operations.

That is what, on April 14th, made the testimony of Charles S. Riley, a clerk at a Massachusetts plumbing-and-steam-fitting company, so explosive. A letter from Riley had been published in the Northampton Daily Herald in March of the previous year, describing the water-cure torture of Tobeniano Ealdama, the presidente of the town of Igbaras, where Riley, then a sergeant in the 26th Volunteer Infantry, had been stationed. Herbert Welsh had learned of Riley, and enlisted him, among other soldiers, to testify before the committee. Amid the bullying questions of pro-war senators, Riley’s account of the events of November 27, 1900, unfolded, and it was startlingly at odds with most official accounts. Upon entering the town’s convent, which had been seized as a headquarters, Riley had witnessed Ealdama being bound and forced full of water, while supervised by a contract surgeon and Captain Edwin Glenn, a judge advocate. Ealdama’s throat had been “held so he could not prevent swallowing the water, so that he had to allow the water to run into his stomach”; the water was then “forced out of him by pressing a foot on his stomach or else with [the soldiers’] hands.” The ostensible goal of the water cure was to obtain intelligence: after a second round of torture, carried out in front of the convent by a “water detail” of five or six men, Ealdama confessed to serving as a captain in the insurgency. He then led U.S. forces into the bush in search of insurgents. After their return to Igbaras, that night, Glenn had ordered that the town, consisting of between four and five hundred houses, be burned to the ground, as Riley explained, “on account of the condition of affairs exposed by the treatment.”

Riley’s testimony, which was confirmed by another member of the unit, was inconvenient, especially coming after official declarations about America’s “civilized” warfare. The next day, Secretary of War Root directed that a court-martial be held in San Francisco and cabled the general in charge of the Philippines to transport to the West Coast Glenn and any witnesses who could be located. “The President desires to know in the fullest and most circumstantial manner all the facts, nothing concealed and no man being for any reason favored or shielded,” Root declared. Yet in the cable Root assured the general, well in advance of the facts, that “the violations of law and humanity, of which these cases, if true, are examples, will prove to be few and occasional, and not to characterize the conduct of the army generally in the Philippines.” Most significant, though, was the decision, possibly at Glenn’s request, to shift the location of the court-martial from San Francisco to Catbalogan, in the Philippines, close to sympathetic officers fighting a war, and an ocean away from the accusing witnesses, whose units had returned home. Glenn had objected to a trial in America because, he said, there was a “high state of excitement in the United States upon the subject of the so-called water cure and the consequent misunderstanding of what was meant by that term.”

The trial lasted a week. When Ealdama testified about his experience-“My stomach and throat pained me, and also the nose where they passed the salt water through”-Glenn interrupted, trying to minimize the man’s suffering by claiming (incorrectly) that Ealdama had stated that he had experienced pain only “as [the water] passed through.” Glenn defended his innocence by defending the water cure itself. He maintained that the torture of Ealdama was “a legitimate exercise of force under the laws of war,” being “justified by military necessity.” In making this case, Glenn shifted the focus to the enemy’s tactics. He emphasized the treachery of Ealdama, who had been tried and convicted by a military commission a year earlier as a “war traitor,” for aiding the insurgency. Testimony was presented by U.S. military officers and Filipinos concerning the insurgency’s guerrilla tactics, which violated the norms of “civilized war.” Found guilty, Glenn was sentenced to a one-month suspension and a fifty-dollar fine. “The court is thus lenient,” the sentence read, “on account of the circumstances as shown in evidence.” (Glenn retired from the Army, in 1919, as a brigadier general.) Meanwhile, Ealdama, twice tortured by Glenn’s forces, was serving a sentence of ten years’ hard labor; he had been temporarily released to enable him to testify against his torturer.

The vote of the court-martial at Catbalogan had been unanimous, but at least one prominent dissenter within the Army registered his disapproval. Judge Advocate General George B. Davis, forwarding the trial records to Root, wrote an introductory memorandum that seethed with indignation. Glenn’s sentence, in his view, was “inadequate to the offense established by the testimony of the witnesses and the admission of the accused.” Paragraph 16 of the General Orders, No. 100, the Army’s Civil War-era combat regulations, could not have been clearer: “Military necessity does not admit of cruelty-that is, the infliction of suffering for the sake of suffering or for revenge, nor of maiming or wounding except in fight, nor of torture to extort confessions.” Davis conceded that, in a “rare or isolated case,” force might legitimately be used in “obtaining the unwilling service” of a guide, if justified as a “measure of emergency.” But a careful examination of the events preceding the tortures at Igbaras revealed that “no such case existed.” Furthermore, Glenn had described the water cure as “the habitual method of obtaining information from individual insurgents”-in other words, as “a method of conducting operations.” But the operational use of torture, Davis stressed, was strictly forbidden. Regarding a subsequent water-cure court-martial, he wrote, “No modern state, which is a party to international law, can sanction, either expressly or by a silence which imports consent, a resort to torture with a view to obtain confessions, as an incident to its military operations.” Otherwise, he inquired, “where is the line to be drawn?” And he rehearsed an unsettling, judicial calibration of pain:

Shall the victim be suspended, head down, over the smoke of a smouldering fire; shall he be tightly bound and dropped from a distance of several feet; shall he be beaten with rods; shall his shins be rubbed with a broomstick until they bleed?

The questions were so vile and absurd-they were the kind that the Filipinos’ Spanish tormentors had once asked-that it seemed “hardly necessary to pursue the subject further.” The United States, he concluded, “can not afford to sanction the addition of torture to the several forms of force which may be legitimately employed in war.” Glenn’s sentence, however, stood. This would be perhaps the most intensive effort by the War Department to punish those who practiced the water cure in the Philippines.

Confronted with the facts provided by the Waller, Smith, and Glenn courts-martial, and with the testimony of a dozen more soldier witnesses who had followed Riley, Administration officials, military officers, and pro-war journalists launched a vigorous campaign in defense of the Army and the war. Their arguments were passionate and wide-ranging, and sometimes contradictory. Some simply attacked the war’s critics, those who sought political advantage by crying out that “our soldiers are barbarous savages,” as one major general put it. Some contended that atrocities were the exclusive province of the Macabebe Scouts, collaborationist Filipino troops over whom, it was alleged, U.S. officers had little control. Some denied, on racial grounds, that Filipinos were owed the “protective” limits of “civilized warfare.” When, during the committee hearings, Senator Joseph Rawlins had asked General Robert Hughes whether the burning of Filipino homes by advancing U.S. troops was “within the ordinary rules of civilized warfare,” Hughes had replied succinctly, “These people are not civilized.” More generally, some people, while conceding that American soldiers had engaged in “cruelties,” insisted that the behavior reflected the barbaric sensibilities of the Filipinos. “I think I know why these things have happened,” Lodge offered in a Senate speech in May. They had “grown out of the conditions of warfare, of the war that was waged by the Filipinos themselves, a semicivilized people, with all the tendencies and characteristics of Asiatics, with the Asiatic indifference to life, with the Asiatic treachery and the Asiatic cruelty, all tinctured and increased by three hundred years of subjection to Spain.” As the military physician Henry Rowland later phrased it, the American soldiers’ “lust of slaughter” was “reflected from the faces of those around them.”

In his private and public considerations of the question of “cruelties,” Theodore Roosevelt-who had been President since McKinley’s assassination, in September of 1901-lurched from intolerance for torture to attempts to rationalize it and outrage at the antiwar activists who made it a public issue. Writing to a friend, he admitted that, faced with a “very treacherous” enemy, “not a few of the officers, especially those of the native scouts, and not a few of the enlisted men, began to use the old Filipino method of mild torture, the water cure.” Roosevelt was convinced that “nobody was seriously damaged,” whereas “the Filipinos had inflicted incredible tortures upon our own people.” Still, he wrote, “torture is not a thing that we can tolerate.” In a May, 1902, Memorial Day address before assembled veterans at Arlington National Cemetery, Roosevelt deplored the “wholly exceptional” atrocities by American troops: “Determined and unswerving effort must be made, and has been and is being made, to find out every instance of barbarity on the part of our troops, to punish those guilty of it, and to take, if possible, even stronger measures than have already been taken to minimize or prevent the occurrence of all such acts in the future.” But he deplored the nation’s betrayal by anti-imperialist critics “who traduce our armies in the Philippines.” In conquering the Philippines, he claimed, the United States was, in fact, dissolving “cruelty” in the form of Aguinaldo’s regime. “Our armies do more than bring peace, do more than bring order,” he said. “They bring freedom.” Such wars were as historically necessary as they were difficult to contain: “The warfare that has extended the boundaries of civilization at the expense of barbarism and savagery has been for centuries one of the most potent factors in the progress of humanity. Yet from its very nature it has always and everywhere been liable to dark abuses.”

There was, of course, an easier way than argument to end the debate. On July 4, 1902 (as if on cue from John Philip Sousa), Roosevelt declared victory in the Philippines. Remaining insurgents would be politically downgraded to “brigands.” Although the United States ruled over the Philippines for the next four decades, the violence was now, in some sense, a problem in someone else’s country. Activists in the United States continued to pursue witnesses and urge renewed Senate investigation, but with little success; in February, 1903, Lodge’s Republican-controlled committee voted to end its inquiry into the allegations of torture. The public became inured to what had, only months earlier, been alarming revelations. As early as April 16, 1902, the New York World described the “American Public” sitting down to eat its breakfast with a newspaper full of Philippine atrocities:

It sips its coffee and reads of its soldiers administering the “water cure” to rebels; of how water with handfuls of salt thrown in to make it more efficacious, is forced down the throats of the patients until their bodies become distended to the point of bursting; of how our soldiers then jump on the distended bodies to force the water out quickly so that the “treatment” can begin all over again. The American Public takes another sip of its coffee and remarks, “How very unpleasant!”

“But where is that vast national outburst of astounded horror which an old-fashioned America would have predicted at the reading of such news?” the World asked. “Is it lost somewhere in the 8,000 miles that divide us from the scenes of these abominations? Is it led astray by the darker skins of the alien race among which these abominations are perpetrated? Or is it rotted away by that inevitable demoralization which the wrong-doing of a great nation must inflict on the consciences of the least of its citizens?”

Responding to the verdict in the Glenn court-martial, Judge Advocate General Davis had suggested that the question it implicitly posed-how much was global power worth in other people’s pain?-was one no moral nation could legitimately ask. As the investigation of the water cure ended and the memory of faraway torture faded, Americans answered it with their silence. ♦

Source: http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2008/02/25/080225fa_fact_kramer?currentPage=all