Under the Radar

On September 27, 2007, the University of Hawai‘i (UH) Board of Regents approved a new contract for a University Affiliated Research Center (UARC), a classified Navy-sponsored research center at the University of Hawai‘i (UH). The UARC resurfaced two years after a coalition of students, faculty and community allies occupied the UH President’s office for a week in protest of such a plan. Opposition from the major UH constituencies including Native Hawaiians, students and faculty led interim Manoa Chancellor Denise Konan to reject the UARC on the Manoa campus. But UH President David McClain overrode Konan to administer the UARC at the UH system level.

While UARC proponents say the contract is a vehicle that could bring in $50 million over five years, opponents argue that it represents the encroachment of the “military industrial complex” into UH, violates its core values as a Native Hawaiian place of learning and turns the Manoa campus into a U.S. Navy lab.

The Administration has said that the UARC will not accept classified projects in the first three years, yet the base contract assigns “secret” level classification to the entire facility, making the release of any information subject to the Navy’s approval. Among the concerns is that the growth of secret non-bid contracts under the UARC increases the risk of corruption, abuses of power and lack of accountability.

An Illicit Creation:

This article is drawn from the new report The Dirty Secret About UARC that uncovers the hidden origins of the UARC based on a two and a half year investigation involving federal and state freedom of information requests, interviews and attempted interviews with key players, and background research about federal contracting, congressional appropriations and defense technologies. The saga of the scandal began as early as 2001 with two Navy grants to UH that have been embroiled in a Navy criminal investigation and an aborted $50 million Research Corporation of the University of Hawai‘i (RCUH) proposal to the Navy called “Project Kai e‘e” (meaning tsunami or tidal wave in Hawaiian), which was intended to become the UARC. The results of the Navy criminal investigation are not known at this time.

The UARC was born from questionable contract activities involving Navy admirals, Naval research

program managers, UH researchers, military contractors, high ranking UH and RCUH officials and congressionally earmarked programs that have been the subjects of federal investigations. The suspicious circumstances surrounding the termination of the Project Kai e‘e proposal and the UARC’s creation by sole source award of a monopoly contract have raised serious questions about the legality and ethics of the procurement.

Furthermore, government secrecy has denied the public access to contracts and financial information, thereby making it impossible to assess the legality of the UARC process and evaluate the risks and potential impacts of undertaking a UARC. To critics of the UARC, the obstruction of public information and accountability amounts to a de facto cover-up. Ironically, the secrecy masking the UARC’s troubled beginnings illustrates the dangers critics have warned about.

The criminal investigation stems from complaints filed with federal authorities in the summer of 2003 by a UH Facilities Security Officer Jim Wingo, a whistleblower who accused Mun Won Fenton, an Office of Naval Research (ONR) program manager and the Navy’s designated “point of contact” for the creation of the UARC of “1) abuse of authority, 2) significant mismanagement of classified contracts, and 3) potential leaks of classified information, classified information lost, compromised, and unauthorized disclosure.” Fenton oversaw several military sponsored research grants and contracts to UH worth several million dollars. She has not returned repeated telephone calls for an interview.

Wingo’s complaint also implicated three of these Navy-sponsored grants and contracts:

Theater Missile Defense: awarded to UH in July 2001 for sensor integration research related to Theater Missile Defense. Initially valued at $238,000, the grant was increased several times to a total of $645,862. Electrical engineering professor Audra Bullock was the Principal Investigator (PI).

High Frequency Scanned Array: awarded to UH in March 2001 for research related to an advanced radar system (UESA) in the amount of $246,375. The grant was increased to a total of $1,462,759 with a promise of an additional $50,000 future funding. However the project terminated early and $9,547.61 was eventually returned. UH professor Michael DeLisio was the initial PI, until electrical engineering professor Vassilis Syrmos took over after December 2001.

Next Generation Radar: a contract awarded to RCUH in December 2002 related to “Sensor Integration and Testbed Technologies.” The award was valued at $1,163,028 with Vassilis Syrmos as the PI. It involved continuing research on the UESA radar, which was called the “Next Generation Radar”.

On March 2, 2005, the Ka Leo o Hawai‘i newspaper broke the story that the Navy Criminal Investigation Service was investigating Fenton and several Navy grants and contracts with UH. It reported that funds granted to UH by the Navy were allegedly used improperly to prepare another RCUH proposal, which is now known to be “Project Kai e‘e.” While the UH Administration denies any wrong-doing on the part of UH faculty or that the criminal investigation has any connection to the UARC, mounting evidence firmly links the UARC to this corruption scandal.

Early Warning Signs: Modular Command Center and Tactical Component Network

Sometime in 2000, Fenton and Rear Admiral Paul S. Schultz, commander of the Amphibious Group ONE sought to establish a network-centric warfare program on Kaua‘i based on a new and controversial technology called Tactical Component Network (TCN). Because TCN was perceived as a threat to the established Cooperative Engagement Capability (CEC) system, the Navy may have blocked any contracting related to TCN.

According to John Monacci, the program manager recruited by Fenton to head the TCN project in Hawai‘i, Fenton and Schultz sought to bypass normal procurement channels to establish the TCN system in Hawai‘i, initially using UH research grants as cover to avoid resistance from hostile Navy officials. Monacci says the strategy was to “disguise” the TCN demonstration as “CEC pre-planned product improvements.” The TCN was installed on ships under Schultz’s command to undergo testing and evaluation at the Pacific Missile Range Facility (PMRF) on Kaua‘i. Schultz named his particular application of the TCN the “Modular Command Center” (MCC).

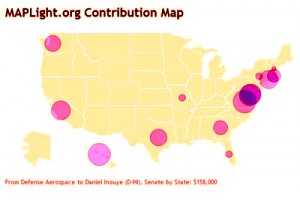

According to Monacci, Fenton lobbied Senator Daniel Inouye to secure funding for these programs. On July 27, 2000, the Senator announced that he had successfully secured Fiscal Year 2001 Defense Appropriations

totaling $150.5 million for PMRF programs. This included $10 million for “CEC improvements,” $11.5 million for “Theater Missile Defense new sensors,” $10 million for “UESA signal processing,” and $10 million for “Tactical Component Network demonstration”.

Irregularities in Hiring and Appropriations:

Only three days into her new job at UH in 2000, electrical engineering professor Audra Bullock met Fenton, who invited her to submit a research proposal to the Navy. Looking back on the fateful meeting, Bullock ruefully joked, “I probably should have stayed home that day.”

According to Bullock, Fenton asked her to write a laser sensors research proposal that was part of a larger Tactical Component Network proposal. Bullock said she was told that the grant was intended to initiate a working relationship between ONR and UH that could lead to an Indefinite Deliverable / Indefinite Quantity (IDIQ) capacity contract. IDIQs are a type of non-bid monopoly contract that has become widely abused since 2000, according to a 2004 Report of the House Committee on Government Reform. The UARC is a sole source IDIQ contract.

After Bullock received the initial grant, Fenton added funds to the grant that more than doubled the award. Bullock said that Fenton then directed her to hire John Monacci as the program manager. As the Principal Investigator (PI) for the project, Bullock was supposed to manage the finances and personnel as well as oversee the research work performed.

However, according to Monacci, “Audra Bullock didn’t oversee anything;” she was “a very nice person” who was “naïve to how Fenton was using her.”

Monacci said that he actually worked under Syrmos and was managed by Fenton and Schultz. Monacci’s job was to install a TCN system on several ships and units under Schultz’s command including the USS Essex, USS Blue Ridge, and an AEGIS cruiser along with ground units from the Marine Corps and to test the system at PMRF on Kaua‘i. This project matches the description of the “CEC pre-planned product improvement” in Department of Defense budget justification sheets, which was identified as a Congressional earmark.

Bullock said that several months later, Fenton instructed her to hire two others from the Pacific Missile Range Facility: Debby Gatioan and John Grandfield. At the time, Bullock expressed concerns to Fenton about having to hire additional employees who were unrelated to her research project. Further, Bullock was concerned that she did not have sufficient funds in the grant to pay two more people. According to Bullock, Fenton promised that Gatioan and Grandfield would be moved off the grant as soon as other funding came through. Gatioan’s job as “UESA Administrative Specialist” and Grandfield’s as “UESA Electrical Engineer” were unrelated to Bullock’s laser sensors research.

Bullock said that in her final report to her sponsors she indicated that she only directly oversaw approximately $150,000 out of the total $645,862 grant and she did not supervise the work of the personnel that the Navy directed her to hire.

UH records show that there was a modification to Bullock’s Grant in July 27, 2001 adding $309,862 to the award. On June 25, 2002 there was another modification adding $100,000 and extending the Grant until May 31, 2003. UH has refused to release Bullock’s actual grant contract, reports or finances.

According to Monacci, Fenton and Schultz were assembling a team to run the MCC/TCN integration program and develop a much larger sensor integration proposal, which came to be called “Project Kai e‘e.”

Monacci said that when Admiral Schultz wanted him to hire another Navy associate John Iwaniec on the TCN grant, he refused because he believed the request was improper. Monacci claimed that since he did not cooperate, Fenton pressured Syrmos to terminate him. Monacci was fired in December 2001. Syrmos said that subsequently, Fenton directed him to hire Iwaniec onto the UESA grant.

The Rise and Fall of Project Kai e‘e:

During his employment on Bullock’s grant, Monacci wrote a concept paper for a multifaceted “Pacific Operations Institute” based in Hawai‘i that would integrate research, testing and evaluation and business development. According to Monacci, it was the initial concept that gave rise to the UARC, the Hawaii Engineering and Design Center and the Hawaii Technology Development Venture.

Fenton revised the plan and renamed it the “Pacific Research Laboratory” (PRL). Fenton’s draft insisted, “Contracting… Provide fast/efficient streamlined contracting for DoD customers… THIS IS THE MOST IMPORTANT CORE COMPETENCE OF PRL!!!”

Once the overall concept for a federal research center was sketched out, Monacci began writing a sensor integration proposal to be submitted by RCUH in response to a Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR) solicitation Broad Agency Announcement (BAA) N00421-01-R-0176 for “Sensors Integration and Communications Technologies.”

The RCUH proposal incorporated proposals prepared by seven UH faculty and compiled by Syrmos. Monacci also incorporated proposals from several defense contractors, including Oceanit, ORINCON, Solipsys, Cambridge Research Associates, SAIC, SYS, and WR Systems.

ORINCON (prior to its acquisition by Lockheed Martin) was a local defense contractor that developed network centric warfare technologies, including a proprietary system called “Web-centric warfare.” Larry Cutshaw, the Director of Business Development for ORINCON, is married to Kathy Cutshaw, UH Manoa Vice Chancellor for Administration, Finance, and Operations, who negotiated the first proposed UARC contract.

Cambridge Research Associates (CRA) produced battle-space visualization software called “PowerScene” that was being utilized in sensor integration testing. Both “Web-centric warfare” and “PowerScene” turned up later in a press release from Senator Inouye as programs eligible to compete for UARC funding.

Oceanit was a company involved in the UESA program and other missile defense projects on Kaua‘i. Prior to being hired onto Bullock’s grant, Debby Gatioan worked for Oceanit and was a Navy point of contact for an industry briefing related to the above mentioned “Sensors Integration and Communications Technologies”

solicitation.

RCUH and its Executive Director Harold Masumoto were key players in moving this project along. Masumoto, the consummate political insider, has through several UH administrations worked behind the scenes to shape key UH decisions. At the June 1, 2001 RCUH Board of Directors meeting, he reported “RCUH’s assistance is needed by the Navy for missile program project at PMRF because of the classified nature of the work to be done.”

Then at the October 4, 2001 RCUH Board of Directors meeting, Masumoto reported, “This may become a major project – about $50 million if funding comes through. As more of these types of projects become reality, there may be a need for a separate entity to manage them because of their focused objectives.”

RCUH and Funding Anomalies:

Established by the State legislature in 1965 to support research activities at UH, RCUH was exempted from various state laws governing procurement and personnel in order to provide more flexible and expedient administrative and financial services than a typical state agency could perform. While it fulfilled important and legitimate functions for researchers, RCUH also gained a reputation for lack of transparency and accountability. In a 1993 report the State Auditor found that RCUH “operates with little accountability and oversight by either the university or its Board of Directors.”

Around May 2003, Bullock asked Masumoto to remove Grandfield and Gatioan from the contract payroll, which he agreed to do. But some time later, Bullock received a notice from RCUH for an unauthorized payroll transaction. She complained to RCUH and was told that Brenda Kanno, the RCUH Executive Secretary, authorized the payroll transaction with funds from another, unspecified source. Bullock said this transaction came as a shock to her, who as the principal investigator was supposed to authorize all payroll transactions on her grant.

In fact, RCUH employment records show that Gatioan and Grandfield were employed by RCUH under job descriptions created for Bullock’s grant long after the grant itself had expired, while the funding sources for their payroll changed several times. Both Gatioan and Grandfield were moved off of the College of Engineering funding on September 15, 2002, which corresponds to the timeframe when Project Kai e‘e was abandoned.

The minutes of the March 2002 RCUH Board of Directors meeting stated: “Executive Director Masumoto reported that we should know within a month or so whether this project will be funded for $48 million over a five-year period. The project is related to missile defense and is basically in support of the Pacific Missile Range Facility. This is a direct project (not a UH project) in which RCUH is the applicant for the funds. The intent is that RCUH will “incubate” the project and then later there will be a new home base for it. The long-range objective is to make this a federal research center similar to national labs such as Sandia, etc. There is great potential for this project.”

Five months after Masumoto’s optimistic forecast, Project Kai e‘e was abruptly and inexplicably aborted. The minutes of the September 27, 2002 RCUH Board of Directors meeting contained only a terse and vague statement about its cancellation: “ONR Project – The proposal for Project Kai e‘e was withdrawn due to circumstances beyond our control. RCUH will pursue other avenues of funding for these types of projects.”

“Things began to fall apart,” explains Monacci. He said that Schultz’s superiors at NAVSEA shut down the MCC/TCN program in Hawai‘i. John Grandfield said he believed that the proposal was withdrawn to avoid RCUH being implicated in possible illegal activities.

Monacci said that Schultz was demoted to a desk job. Admiral Schultz’s service transcript indicates that he was reassigned to be Commander, Military Sealift Command (Special Assistant) from April 2002 to June 1, 2003, at which point he retired at the reduced rank of Captain. Thus far, the Navy, RCUH and UH have failed to respond to freedom of information (FOIA) requests to produce documents related to Project Kai e‘e.

Current RCUH Executive Director Mike Hamnett said that the proposal files for Project Kai e‘e were shredded and thrown away.

Masumoto said in an interview, “Project Kai e‘e, project whatever, I don’t know what the hell they are anymore… You got to understand people like me. I don’t speculate in answering questions to people like you. Okay? You can’t quote me because I’m not going to tell you anything that you can quote me on.”

Moving Towards UARC: Secrecy and Deceptions

Once Project Kai e‘e was scrapped, Masumoto shifted gears to directly pursue the UARC designation, preparing the documents for Senator Inouye’s staff and pitching the UARC to then UH President Evan Dobelle and UHM Chancellor Peter Englert.

In a 2005 public meeting on the UARC, Englert denied that there was any connection between the UARC and the investigation of the Navy grants. He also denied having any dealings with Masumoto or Fenton about the UARC. He was not telling the truth. In a December 6, 2002 letter to Cohen, Englert wrote: “Currently we are working with Ms. Mun Won Fenton at ONR… to create a preliminary management plan that will serve as the road map of the University’s core competencies. Furthermore, Mr. Harold Masumoto, Executive Director of the Research Corporation of the University of Hawaii, has briefed Mr. John Young, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, on our intention to apply for a UARC at UHM.”

Under Masumoto the UARC plans moved swiftly, but turbulence from the unseen events that had led to the cancellation of Project Kai e‘e continued for months afterwards. By 2003, the relationship between Fenton and Syrmos grew unbearably strained when Syrmos allegedly refused to go along with changes Fenton wanted to make. Gaines said that he believed Fenton classified several projects in order to remove Syrmos from them.

According to Syrmos, in the spring of 2003 several pieces of information were classified on the Next Generation Radar project. Heightened security restrictions in the wake of September 11, 2001, ensured that Syrmos, as a foreign born researcher, would not easily attain security clearance. As a result, he was temporarily forced off the UESA and Next Generation projects. On May 13, 2003, Masumoto hinted to the RCUH Board of Directors that there were problems brewing: “Security Issue – We have a situation where a project started as an unclassified project, but the Navy has now decided to classify it. Issue is safeguarding the appropriate data and allowing access to cleared employees only in a secure facility.”

Irregularities in the classification procedures prompted UH Facilities Security Officer James Wingo to file complaints with federal authorities in July 2003, which led to the investigations reported in the Ka Leo paper

almost two years later.

Although Iwaniec and Gatioan were still employed under their original job descriptions, the source of their payrolls switched to PICHTR on July 15, 2003. Several days later, on July 22, 2003, Masumoto resigned from RCUH and assumed a full-time role at PICHTR.

But Masumoto maintained a hidden hand in the UARC process. On July 1, 2003, he signed a $60,000 consultancy contract with RCUH to help secure the UARC for UH. After extending the contract to June 30, 2005, and with several months remaining on his contract, Masumoto abruptly terminated the agreement and his security clearance on March 31, 2005 shortly after news of the Navy criminal investigation broke.

Irregularities in UARC Designation for UH

Opponents of the UARC point out that contrary to Federal Acquisition Regulations and Department of Defense guidance requiring competition in the awarding of UARC contracts, NAVSEA awarded the ARL/UH without any competition. In other recently created UARCs, the Army, NASA and the Department of Homeland Security used extensive competition in selecting the recipients of the contracts.

Before a Hawai‘i State Senate committee Syrmos testified that the UARC was competitively procured through a Broad Agency Announcement (BAA), a widely distributed competitive procurement announcement. When an audience member challenged his statement, Syrmos corrected himself and said that there was a Request for Proposals (RFP) issued on September 24, 2004. This wasn’t true either. A presolicitation Notice dated September 24, 2004, stated: “The Naval Sea System Command intends to award a sole source contract for up to 315 work years to establish and further solidify a strategic relationship for essential Engineering, Research, and Development capabilities…”

In the case of the UH UARC, Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) UARC managers were forced to contrive a justification to procure a new UARC that they neither needed nor wanted. Furthermore, despite Freedom of Information requests filed nearly two years ago, NAVSEA has failed to provide the required justification and certification for the sole source procurement of the UARC to the University of Hawai‘i. Fenton and Schultz have not returned repeated phone calls for interviews. Senator Inouye’s office has not responded to requests for information.

Kyle Kajihiro is program director for DMZ Hawaii. For his full investigative report, The Dirty Secret About UARC, go to stopuarc.info. Email: kkajihiro@afsc.org.

October 9, 2007

Kyle Kajihiro

Source: http://www.haleakalatimes.com/2007/10/09/under_the_radar/