I ka wā ma mua, ka wā ma hope: Exploring Pearl Harbor’s present pasts

Here’s an article I wrote for the Hawaii Independent reflecting on a recent school excursion to Ke Awalau o Pu’uloa / Pearl Harbor, and contemporary meanings of Pearl Harbor as national myth:

I ka wā ma mua, ka wā ma hope: Exploring Pearl Harbor’s present pasts

By Kyle Kajihiro

HONOLULU—On the eve of the 70th anniversary of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, I helped lead a field trip to Ke Awalau o Puʻuloa (Pearl Harbor) for 57 inner-city Honolulu high school students. We were studying the history of World War II, its root causes, consequences, and lessons. We also sought to uncover the buried history of Ke Awalau o Puʻuloa, once a life-giving treasure for the native inhabitants of O‘ahu, the object of U.S. imperial desire and raison d’etre for the overthrow and annexation of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

A recurring theme in this excursion was the ʻōlelo noʻeau or Hawaiian proverb: “I ka wā ma mua, ka wā ma hope” “In the time in front (the past), the time in back (the future).” Kanaka Maoli view the world by looking back at what came before because the past is rich in knowledge and wisdom that must inform the perspectives and actions in the present and future. Or another way to say it might be to quote from William Faulkner’s Requiem for a Nun: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Throughout our field trip, the past kept reasserting itself into our present.

To prepare for our visit, we impressed upon the youth that while our objective was to engage in critical historical investigation, we needed to maintain a solemn respect for Ke Awalau o Pu‘uloa as a sacred place and a memorial. It is a place where the blood and remains of many who died in battle mingle with the bones of ancient Kanaka Maoli chiefs lying beneath asphalt and limestone on Moku‘ume‘ume (Ford Island). It is a wahi pana, a legendary place, where the great shark goddess Kaʻahupāhau issued a kapu on the taking of human life after she killed a girl in a rage and was later overcome with remorse. It is also where Kanekuaʻana, a great moʻo wahine, female water lizard, provided abundant seafood for the residents of ʻEwa until bad decisions by the chiefs caused her to take away all the pipi, ʻōpae, nehu, pāpaʻi, and iʻa.

Our students were all poor and working class youth of Filipino, Samoan, Tongan, Chinese, Vietnamese, Micronesian, and Native Hawaiian ancestry. Their ethnic origins tell their own history of war and imperialism in the Pacific. We asked them to consider whose stories were being told, whose were excluded, and who was the intended audience.

We asked them to consider whose stories were being told, whose were excluded, and who was the intended audience.A large floor map of the Pacific at the entrance to the museum provided a great teaching aide for illustrating the competing imperialisms in the Pacific that led to World War II. As students played the role of different colonized nations, we described the simultaneous expansion of Japan as an Asian empire and the rise of the United States via its westward expansion across the Pacific. I couldn’t help but reflect on how much President Barack Obama’s recent foreign policy “pivot” to the Pacific in order to contain the rise of China echoed these earlier developments.

Inside the “World War II Valor in the Pacific” museum, we explored the roots of World War II, the differing U.S. and Japanese perceptions of the U.S. military build-up in Hawai‘i, and the seeds of World War II in the devastation caused by World War I and the Great Depression. We discussed the impacts of martial law and racial discrimination against persons of Japanese ancestry during the war.

The section on the Japanese internment took on a new sense of urgency in light of the recent U.S. Senate vote authorizing the indefinite detention of U.S. citizens accused of supporting terrorism without due process. Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) arguing against inclusion of this clause in the Defense Authorization Act said:

“We as a Congress are being asked, for the first time certainly since I have been in this body, to affirmatively authorize that an American citizen can be picked up and held indefinitely without being charged or tried. That is a very big deal, because in 1971 we passed a law that said you cannot do this. This was after the internment of Japanese-American citizens in World War II. […] What we are talking about here is the right of our government, as specifically authorized in a law by Congress, to say that a citizen of the United States can be arrested and essentially held without trial forever.”

But the measure passed 55 to 45. One of the tragic ironies is that among the senators voting to keep the indefinite detention clause in the bill was Sen. Daniel Inouye (D—HI) whose own people were unjustly interned in concentration camps during World War II.

After taking in the effects of institutionalized discrimination, we continued on through the museum. To its credit, the National Parks Service included information about Ke Awalau o Pu‘uloa as an important resource and cultural treasure for Kanaka Maoli. However, the “Hawaiian Story” was relegated to set of displays outside the exhibit proper. In this marginal space where Kanaka Maoli and locals are allowed to tell our history, most visitors rest their feet with their backs to the displays. Once I saw a person sleeping in front of a plaque that contained the sole reference to Hawai‘i’s contested sovereignty: “The Kingdom of Hawai‘i was overthrown in 1893.”

The first thing that jumps out from this line is the passive third-person voice, as if the overthrow of a sovereign country just happened by an act of God, when in fact, it was an “act of war” by U.S. troops that enabled a small gang of Haole businessmen to overthrow the Queen. Still, according to a National Park Service official, this watered down reference to the overthrow was one of the most controversial lines in the exhibit.

In their book Oh, Say, Can You See? The Semiotics of the Military in Hawai‘i, Kathy Ferguson and Phyillis Turnbull describe the hegemonic discourse that obscures alternative narratives:

“The long and troubled history of conquest is muted by official accounts that fold Hawai‘i neatly into the national destiny of the United States. Similarly, the relationships to places and peoples cultivated by Hawai‘i’s indigenous people and immigrant populations are displaced as serious ways of living and recalibrated as quaint forms of local color.”

Another controversial shred of history that made it into the exhibit was a small reference to America’s atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Entitled “Road to Peace,” the small photograph depicted a devastated Hiroshima with its iconic dome. But where were the people? In contrast to the graphic depiction of U.S. casualties in the Pearl Harbor attack, the museum avoided showing the vast human suffering caused by the atomic bombing of Japan. One explanation can be found in the classic study Hiroshima in America: Fifty Years of Denial, by Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell. They argue that U.S. citizens suffer from a collective psychic numbing about the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki: “It has never been easy to reconcile dropping the bomb with a sense of ourselves as a decent people.”

It seems that the U.S. public has also developed a collective psychic numbing about slavery, genocide, and imperialism.It seems that the U.S. public has also developed a collective psychic numbing about slavery, genocide, and imperialism, which brings us back to the role of “Pearl Harbor” as war memorial and national myth. It is as if the Pearl Harbor attack induced a collective post-traumatic stress that haunts the national psyche, a recurring nightmare within which our imaginations have become trapped. And since the United States is now the preeminent superpower, the entire world is held hostage to its nightmares.

As national myth, “Pearl Harbor” reproduces the notion of America’s innocence, goodness, and redemption through militarism and war. It absolves the sins of war while mobilizing endless preparations for war, a constant state of military readiness that has mutated into a war machine of vast, unfathomable proportions. More than 1,000 foreign U.S. military bases garrison the planet. “Pre-emptive war,” military operations other than war, proxy wars, and decapitation strikes by drones have become the norm. As German theologian Dorothee Soelle reminds us, the delusional pursuit of absolute security, shuttering the window of vulnerability, means closing off all air and light and undergoing a kind of spiritual death.

Every time we are scolded to “Remember Pearl Harbor,” the dead are roused from their resting places to man battle stations for imagined future enemies. Haven’t they sacrificed enough? What if we let the dead rest in peace? What if the greatest honor we could afford them was a commitment to peace and not endless war? How would Pearl Harbor be different if it was a peace memorial instead of a war memorial?

After viewing the exhibit, we decided to debrief and reflect on what we saw and experienced. Large tents and white chairs were set up in neat rows for the upcoming commemoration. Seeing visitors sitting under the shade of the tents, we decided to join them. After all, the anniversary of the Pearl Harbor attack is a time of public remembrance and reflection, with amenities and labor paid for by the public.

But before we all could sit down, a sailor in blue camouflage told us we were not allowed to sit on the chairs that they had just spent hours setting up. A teacher reassured him that we would just meet for a few minutes and leave the area as orderly as we found it, but he insisted that we could not sit there. So we all stood up and huddled in the shade.

But the other visitors, who appeared to be Haole and Asian tourists, were allowed to remain seated. I walked up to the two sailors and informed them that there were other people sitting on their chairs and suggested that they also inform those visitors about the “no-sitting” rule.

The sailors became aggressive. One sailor leaned forward to my face, his lips curling into a snarl and his voice raised to intimidate. “Who are you?! What’s your name?!” he fired off. “Who are you with?! What are you doing here?! Why are you telling us how to do our job?!”

He didn’t want my answers. His words were like warning shots from a gun intended to make me seek cover.

I asked why they made us stand while they let the other people sit and argued that they were sending a very bad message to the youth. Unable to explain the inconsistency of their rule, he finally said that they would talk to the other visitors when they “get around to it.” As I walked away, he grunted “Fucking bitch!”

The youth, who had overheard the exchange and witnessed the pent up violence of the sailor’s voice and body language, were abuzz. I told them to pay attention to how we were treated, to who was allowed to sit and who wasn’t. I asked them to reflect on why we were treated this way. Several students blurted out “It’s racism, mister!” “They only care about tourists!”

Sadly, the two sailors were also persons of color. From their looks and name patches, it appeared that they were of Asian and Latino ancestry. I imagine that as low-ranking military personnel, they get yelled at and humiliated all the time. This particular assignment—setting up white chairs and tents for VIP guests, chairs that they will never sit on—must have felt demeaning. So, when a group of youth who look like them came along and casually crossed the class and race line, it surely pushed some buttons.

I have noticed that when colonized people serve in the colonizers’ armies, they often adopt hyper-aggressive attitudes to overcompensate for feelings of humiliation and self-loathing. When troops are conditioned to win respect and authority by demeaning or dominating others, it can spill over into other human interactions. We see evidence of this in the high rates of domestic violence and sexual assault of women in the military. It also helps to explain why it was so natural for the sailor call me an epithet so degrading to women. In other times and other circumstances, he might have called me a “Jap,” “Gook,” “Haji,” “Nigger,” or “Fag.” Those names serve the same function, to dehumanize and put us in our place.

I should thank the two sailors for making an indelible impression about the oppressive nature of military power in Hawaiʻi and the racist and colonial order the military helps to maintain here. I wonder how our students will respond when they are approached by military recruiters in the future (and most of them will be approached by recruiters). Their demographics place them in a high risk category for being recruited into the military.

Recruiters have swarmed schools with large immigrant and low income populations, luring students with incentives and promises of citizenship, education, and career opportunities. A study by the Heritage Foundation of U.S. enlistment rates reported that as of 2005, “Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander” were the most overrepresented group, with a ratio of 7.49, or an overrepresentation of 649 percent.

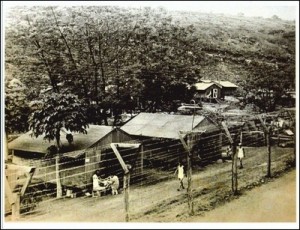

How would Pearl Harbor be different if it was a peace memorial instead of a war memorial?After our inhospitable treatment at the Pearl Harbor memorial, we left for our final stop, the Hanakehau Learning Farm in Waiawa. Just off the main highway, down a few back roads and a dirt trail, the concrete freeway and urban sprawl gave way to a humid, green oasis near the shores of Ke Awalau o Pu‘uloa. As we drove up, a Hawaiian flag flew over the entrance and clear water flowed from springs. The ‘āina lives! But scattered piles of construction debris and weed-choked wetlands told of the arduous work to “restore `āina in an area heavily impacted by a long history of military misuse, illegal dumping, and pollution.”

Andre Perez greeted us and explained their mission “to reclaim and to restore Hawaiian lands and provide the means and resources for Hawaiians to engage in traditional practices by creating Hawaiian cultural space.” Flipping on its head the popular saying “Keep Hawaiian lands in Hawaiian hands,” he explained that it was more important to “Keep Hawaiian hands in Hawaiian lands.” Until Kanaka Maoli practice caring for the ʻāina, they would not have their sovereignty.

The class took a short walk to survey the area and witness the transformation of the environment. What was once clean and productive wetland and ecoestuary system had become a place of social decay and ecological ruin. Sugar growers had built a railroad on an artificial berm that cut off the flow of fresh water to the lochs. Former fishponds were imprisoned by a military fence with signs warning of toxic contamination in the fish and shellfish. This is one of more than 740 military contamination sites identified by the Navy within the Pearl Harbor complex, a giant Superfund site. Now drug addicts and outlaws seek out the secluded brush near Ke Awalau o Puʻuloa to make deals, get high, or strip stolen cars.

Against this backdrop, Hanakehau farm stands out like a kīpuka, an oasis of hope amid the ruins of colonization. The farm represents the resilience of the ‘āina and Hawaiian culture, new growth on devastated lava flow, to transform Pearl Harbor, a place of tragedy and war back into Ke Awalau o Puʻuloa, a source of life and peace.

Andre shared an ʻōlelo noʻeau with the students: “He aliʻi ka ʻāina, he kauā ke kanaka.” The land is chief, and humans are the servants or stewards. This metaphor shows that land is held in high honor and calls on people to take care of the land.

After we returned to the school, the students were given the assignment to create short skits about what they learned during the field trip. Three of the five groups created satirical skits about the absurd “chair incident.” Another group utilized the metaphor of “He aliʻi ka ʻāina, he kauā ke kanaka.” As educators trying to instill critical thinking skills, we couldn’t have asked for a better curriculum.

Our class excursion made me remember another frequently cited quote about the importance of history. The philosopher George Santayana wrote in The Life of Reason: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” This quote has been used frequently to justify constant vigilance and overwhelming military superiority as the prime lessons of World War II. However, as the United States “pivots” its foreign policy to contain a rising China, it seems to be following the catastrophic course of past empires. Perhaps our memories don’t go back far enough to a past when people had peace and security without empire.

Instead of walking away from the past, we might be better off turning to face history, where our past may hold answers to our future.

Umi Perkins also wrote an excellent article in the Hawaii Independent reflecting on the Pearl Harbor commemoration “Pearl Harbor wasn’t always a place of war”.