George Lolashvili

First movement:

People of different epochs, Stravinsky and Shostakovich

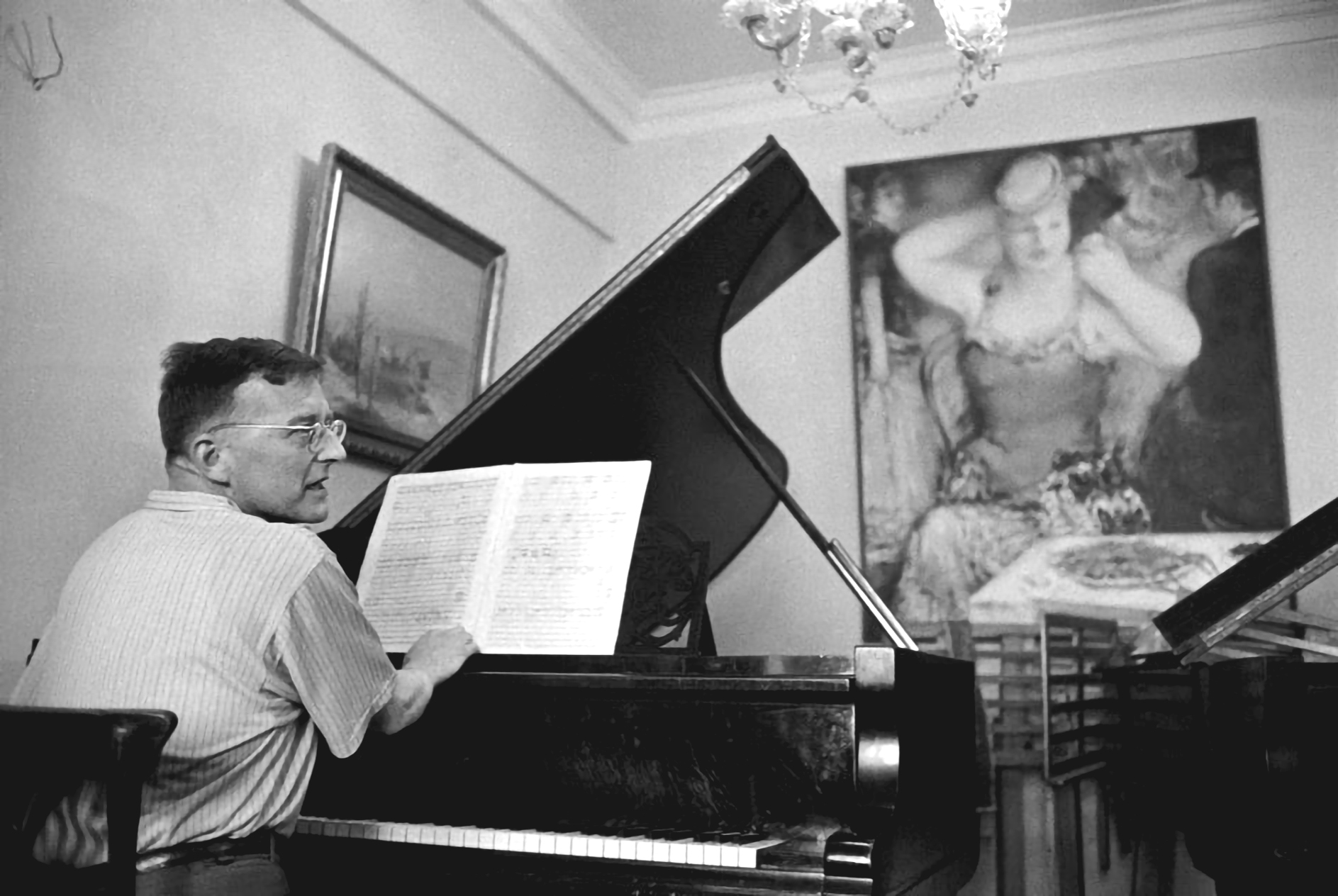

Many special names can be mentioned when we talk about 20th-century Russian classical music, but there are two who can’t be omitted from this discussion. Those names are Igor Stravinsky and Dimitri Shostakovich. The two, regarded as great composers of their generation, are related in many ways: Stravinsky, alongside Mahler, was the biggest influence on Shostakovich, who was 23 years younger. Both of them were born and raised in St. Petersburg and both their families had Polish ancestry. But despite some similarities, the contrast between them tells the story of two different times.

Many special names can be mentioned when we talk about 20th-century Russian classical music, but there are two who can’t be omitted from this discussion. Those names are Igor Stravinsky and Dimitri Shostakovich. The two, regarded as great composers of their generation, are related in many ways: Stravinsky, alongside Mahler, was the biggest influence on Shostakovich, who was 23 years younger. Both of them were born and raised in St. Petersburg and both their families had Polish ancestry. But despite some similarities, the contrast between them tells the story of two different times.

Both Stravinsky and Shostakovich were born in Tsarist Russia, but already at the time of Shostakovich’s birth in 1906, you could hear the trembling of the empire. 1905 was the first attempt of revolution in Russia which was followed by political repressions, but the empire still couldn’t manage to gain its power back, as subsequent cracks were too big to be filled. Then came the October Revolution of 1917, when Dimitri Dimitriyevich Shostakovich was 11 years old. Therefore, it’s not a stretch to say that Shostakovich was a child of the revolution, or the revolutionary times.

On the other hand, when Trotsky stormed the Winter Palace of Petrograd in 1917, Stravinsky already lived in Switzerland and wouldn’t return to Russia until late in his life in 1962. Shostakovich spent his whole life in the USSR, traveled a handful of times on short periods and his entire milieu was Soviet. So, while both Stravinsky and Shostakovich are rightly regarded as the greatest Russian composers of the 20th century, Shostakovich is part of the Soviet history and culture, while Stravinsky is a Russian representative in European classical music of the past century.

The difference between the life paths of Stravinsky and Shostakovich can be demonstrated in the following manner: When the war hit Europe in 1914, Stravinsky fled from Russia to Swiss mountains with his family. He sheltered them there and was able to continue working on his music in peace. In contrast, when Germans sieged Leningrad in 1941, Shostakovich was trapped inside the city with his family and had to experience the horror of the 2-year military blockade first hand. Later, Time Magazine wrote an article about Shostakovich’s Symphony N.6, produced during German bombings of Leningrad. “When guns speak, the muses keep silent, says an old Russian proverb.” – reads the article. “Last winter, as he listened to the roar of German artillery and watched the sputtering of German incendiaries from the roof of Leningrad’s Conservatory of Music, Fire Warden Shostakovich snapped: “Here the muses speak together with the guns.”

Second movement:

Stalin as the editor-in-chief of everything

It was 1936 and the classical music scene had already become familiar with Shostakovich with his Symphonies No.1, 2 and 3. However, the career of promising young composer took a different turn when Stalin stormed out of Moscow’s Bolshoi Theatre in the middle of Shostakovich’s “Lady Macbeth of the Mtensk District”. Stalin had an opinion on everything and sometimes mere expressions of his opinions or reactions like this were enough for his bureaucrats to make it into a political decision. 1936 was also the period of Yezovshchena, the height of political repressions in the USSR, and at that moment some people would think that Stalin’s reaction to the opera was enough of a reason to add Dimitri Dimitriyevich to the list. However, before we follow the story of Shostakovich in the aftermath of this fateful incident, we should talk about the Leader and his ‘peculiar’ input in Soviet arts and literature.

Before his revolutionary career, young Stalin considered himself a poet. His poetry was even published in the most prominent Georgian journal, “Iveria”, several times. Even when he became the leader of the USSR, he always reserved some time for literature. There’s a famous story about the Russian translation of the most important Georgian literary text, “The Knight in Panther’s Skin”. After the translator, Georgian philosopher Shalva Nutsubidze, finished working on it, the manuscript was taken away from him and brought to Stalin. The Leader then edited the whole text and let it be sent to the publishers only after that.

Stalin’s reading was always with an ‘ideological eye’. He scattered through texts almost exclusively searching for the ideas behind them. He had a firm notion of what art was supposed to be: a monumental creative work expressed in universal forms and bound by a positive holistic idea. This is one of the most underrated of Stalin’s legacies: even today the most important question for the teachers of literature in most of the post-Soviet classes is “what’s the core meaning behind the text” and it comes from Stalin’s method of reading.

The primary postulate for art in the Soviet Union was that its value was measured by the (positive) message it carried. And here’s when the term “Formalism” comes in. The biggest way to denounce the art in the Soviet Union was to call it “formalistic”. Formalistic art was what school teachers called “art for art”. It was the opposite of “Socialist Realism”, the official style of Soviet art. Every artistic piece that had meta elements, or tried to experiment with its language, medium, or structure, could be deemed as “formalistic”, and thus, unworthy.

There are several reasons why Stalin had this point of view on art. Most of them were, of course, ideological by nature (and one of them was achieving the highest possible accessibility for common people, summed up in a term “art for the masses”). Stalin understood the mythological importance of common art and its role in creating national and cultural narratives. During World War II, he commissioned Sergey Eisenstein to direct two films on Ivan Grozny, the most important Tsar of medieval Russia. The figure of Ivan Grozny was the figure of an unifier of the nation and Stalin needed to reinforce the sentiment of the national unification under the firm ruler during the breaking point in the war in 1944. Eisenstein gave Stalin what he wanted – an image of a warrior king, an image of unity in authority, the symbol to which Stalin wanted people to relate him.

Third movement:

The birth of the 5th out of the “muddle”

On January 28, 1936, two days after the Leader expressed his discontent with “Lady Macbeth”, an article in Pravda followed suit. “Muddle Instead of Music” – read the title of arguably the most famous Soviet review. This short piece described the opera as “wilderness of musical chaos” that disappointed the appreciative audience. The review made it clear, “Lady Macbeth” was a bourgeois art, not socialist, and “Petty bourgeois ‘innovations’ lead to a break with real art, real science, and real literature “. The article also has a paragraph that sums up both party’s preferences with art and the general sentiment of those years: “The power of good music to infect the masses has been sacrificed to a petty bourgeois, “formalist” attempt to create originality through cheap clowning. It is a game of clever ingenuity that may end very badly”. The last sentence made it clear. The article was not just written to express dissatisfaction, it was a warning. The review was printed without mentioning the author. Usually, this meant that the position articulated in the text was the party’s official stance. The opera was subsequently banned (but not immediately, so these actions didn’t seem too obviously as censoring) and people in musical cycles tried to distance themselves from Shostakovich. He was advised not to perform his Symphony No.4. The composer finished working on the score of the 4th later that same year, but it had an obvious influence of Mahler’s music and the party didn’t appreciate the Austrian composer. The premiere of the 4th was canceled for “administrative measures”, but this time, Shostakovich had to pull the plug himself by withdrawing his 4th from rehearsals. This was a peculiarity of Soviet censorship – it would try to stay indirective and formally untraceable.

The aftermath of the Pravda article became more and more severe as time passed. After two months from the withdrawal of the 4th, Shostakovich’s biggest patron, Marshal Tukhachevsky was arrested and executed for treason. At this point, Dimitri Dimitriyevich was deemed unemployable, and had lost his commissions and powerful friends.

It is important to note that his ‘muddle’ work, including “Lady Macbeth”, was getting good press in the Soviet Union before the incident at the Bolshoi Theatre. Hence, the composer’s ‘fall from grace’ was more painful. However, it didn’t last long.

In November 1937, less than two years after the Pravda article, Shostakovich’s Symphony No.5 had a triumphal premiere in Leningrad. He was fully rehabilitated and received a plethora of awards and compliments from the party in the following weeks. Musicologist Richard Taruskin examines the Soviet reception of the 5th in detail in his article “Public lies and unspeakable truth interpreting Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony”. He describes the immediate reaction as “an orgy of public praise”. “It went for months”, writes Taruskin, “to the point where [the] president of the Leningrad Composer’s Union tried to put on the brakes. On January 29, 1938, the day of the Moscow premiere, he circulated a memorandum comparing the 5th reception to stock manipulations, ballyhoo, even a psychosis that threatened to lead the Soviet music into a climate of creative laissez-faire”.

The Symphony had four movements: Moderato, Allegretto, Largo, and Allegro non troppo. I’ll leave the technicality of the 5th to the musicologists. Instead, what I want to outline here is some of the non-technical analysis that the professional critics offer. The 5th is full of ‘musical gestures’ that can be interpreted as references. Some of them are intertextual and refer to Beethoven, Shostakovich’s previous work, or music of other Russian composers. Some of the references are more syntactic than semantic and give the music effects of certain feelings. However, in all of this web of references that can be read as a text in contemporary tradition, there is one whose significance stands out when compared to others.

As musicologists suggest, the music of the fourth movement in the Symphony invokes panakhina, funeral rites customary to Eastern Orthodoxies. As Taruskin writes in his article, this type of reference was somewhat common in Russian music and was used in Symphonic music as an act of testimony towards certain deceased figures in the past by Stravinsky and other composers. The issue with this kind of reference is that it feels “out of place” and has a different structure. Some argue that it is devoted to his late patron, some say that this was a general expression of his state of mind. According to the recollections of people present at the premiere in Leningrad, in the end, the audience wept. The composer’s intention behind the fourth movement is disputed and there’s no consensus, but if there was an attempt to create an environment appropriate to a panakhina, that was a successful one.

Fourth movement:

Shostakovich in the discourse of Soviet Dissidence

The 5th Symphony was seen by the mouthpieces of the party as an act of personal perestroika, or rehabilitation. The musical evaluation resulted in the same conclusion – the 5th symbolized the individual struggle that was triumphed in rebirth. The interpretation saw 5th as autobiographical and welcomed the perestroika of Shostakovich.

However, as time showed, this was not the ultimate resolution from the party as Dimitri Dimitriyevich faced another wave of denunciation and accusations of formalism later in the ’40s, followed by subsequent rehabilitation into the cultural mainstream.

The most popular narrative regarding Shostakovich’s life comes from “Testimony: Memoirs of Dimitri Shostakovich”, a book by Solomon Volkov. The author claimed that the text was a collection of transcribed talks between him and the composer, but the authenticity of it is highly disputed by both scholars and people close to the composer. Volkov portrayed Shostakovich as someone whose entire life and work were at odds with political power. That struggle is the single most significant drive according to the book and every event and every work goes in its prism.

Testimony was published in 1979, four years after the death of Shostakovich. The author insisted that the manuscript was approved by the composer himself, but the only proof Volkov provided was 8 pages of text with Shostakovich’s signature on them and a photo with Shostakovich’s handwritten message “In memory of our talks”.

The credibility of the book was refuted several times since its publication and our article doesn’t intend to go into details of the claims from each side. There’s a collection of scholarly work published in 2004 under the name “A Shostakovich Casebook” that corroborates all the materials against Volkov’s case. What’s relevant for this article is Volkov’s attempt to portray Shostakovich as an ultimate dissident, who acted as a “holy fool” (or yurodivy in Russian) in the relationship with the state. He gives us an image of a genius who intentionally acted like a fool and found ways to tell the truth in this way. “In the framework of Russian culture,” writes Volkov in the preface of Testimony, “the extraordinary relationship between Stalin and Shostakovich was profoundly traditional: the ambivalent “dialogue” between tsar and yurodivy, and between tsar and poet playing the role of yurodivy in order to survive, takes on a tragic incandescence.”

In the midst of the Cold War, this type of sentiment would sell Volkov’s story better, but it would do Shostakovich injustice as a composer. The composer’s relationship with the State is much more complicated than the scope of the Soviet Union and its dissidents. And his work is more complex than a mere artistic struggle against the power and its ideology.

The image of Shostakovich that Solomon Volkov offered to the Western readers (He never provided the original Russian manuscript and didn’t let the English text be translated into Russian) is just one of many. Testimony can be seen as a revision of the composer’s whole life for a purpose to portray him suitably. Nevertheless, this does not mean that there is no conflict to be seen in Dimitri Dimitriyevich’s career between him and the Soviet state. There is a conflict, but it’s not a fundamental one. The fundamental conflict is located somewhere else and there’s one (obvious) Lacanian concept that helps to understand it. The conflict that I’m referring to is not an explicit social relationship between the Leader and the artist, it’s an internal one where this capital L in the leader becomes the Lacanian big O as in the big Other. In this sense, the Leader is manifested as an alter-ego representing the state, party, or the power in general and it is the source of the internal conflict between the him and the subject. The 5th as I see it, is an expression of this dialectic conflict between the subject and the Other.

When Shostakovich’s 5th was first performed in Leningrad, it had a contrasting reception: People in power or in service of power grasped true socialist essence in it. As for the others, especially the ones who lived in a paranoid social reality because of recent repressions, this was the music that expressed their general feeling of dread. But the idiosyncrasy of Dimitri Dimitriyevich’s case is that his life can be approached in the same way as his 5th: We can hear in it both the sound of the Soviet socialism and the struggle against its symbolic order. Similarly, Shostakovich can be seen both as an image of Soviet music whose face is printed on the Time magazine cover and the composer who wrote the most anticlimactic and ironic Ninth Symphony in response to the Leader’s request. The two contradictory parts make a dialectic whole and I prefer to see the figure of Shostakovich in the same way – as a person of two negating images. His life is more of a conflict than a collection of stories following a certain straight line of sequential decisions, and neither is his music.

Comments by Zammataro