A few weeks ago now, I had the pleasure of attending a discussion focused on the edTPA with colleagues from several local school districts and universities. (For those of you who aren’t familiar with the edTPA, it’s a new performance assessment that is being used as a certification exam in New York State and elsewhere around the country.) Also in attendance was Kathleen Cashin, who was recently re-elected to the New York State Board of Regents. Unlike some of her colleagues, Cashin has spent most of her career working as a teacher and administrator in New York City public schools. While her colleagues on the Board of Regents have done impressive work in the field of education, the majority have never taught in the K-12 public school system in New York State. The majority of the Board is comprised largely of CEOs, philanthropists, and lawyers.

Shouldn’t extensive experience in the field be a prerequisite for making major decisions about education, especially decisions that affect the daily lives of teachers and school children? Without such expertise, policymakers can theorize classroom experience quite a bit, but they can’t really ‘know’ what it’s like to be in the classroom. I believe that part of the reason the policy-practice gap in education persists relates to the fact that so many of the individuals who make decisions about classroom practice are far removed from the realities of teaching and schooling.

My work as a scholar so far has largely focused on the policy-practice gap: the space that exists between policies as they exist on paper and the on-the-ground realities of their implementation in schools. This research was inspired by my experience as a 5th-grade teacher in New York City. My colleagues and I experienced policy implementation as episodic, arbitrary, and disconnected from what we actually needed as classroom teachers and building administrators. We experienced pendulum-like swings in curriculum and 180-degree turns in instructional expectations. It was the early 2000s in New York City, and we were knee-deep in what Michael Fullan calls “projectitis,” when schools “take on or are forced to take on every policy and innovation that comes along” before having the opportunity to see if what they’re doing is working.

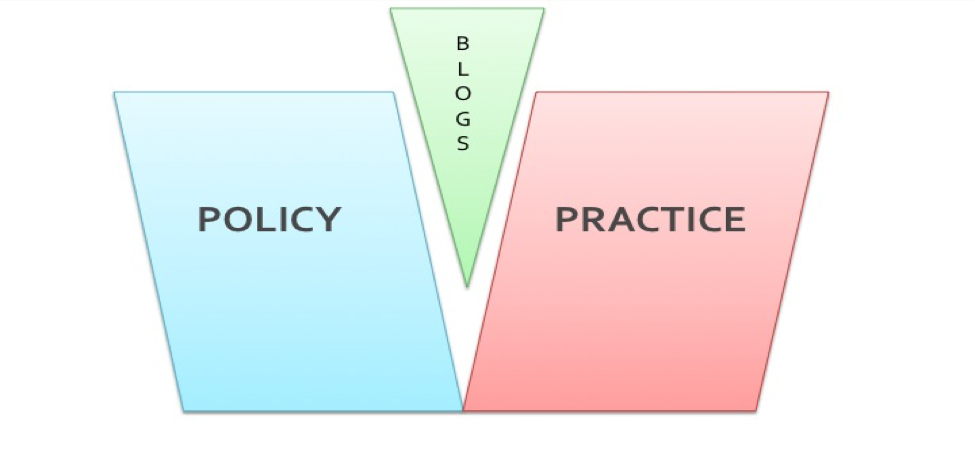

In my dissertation, I wrote about this policy-practice gap with a new idea and hope: why not fill the gap with information teachers are sharing on blogs that they write? I found teachers’ critiques of educational policies shared on their blogs rife with recommendations from the view of the classroom. I thought, if we could just get policymakers to listen to what teachers have to say, we might be able to change something about the educational policymaking process.

I developed this graphic to illustrate my idea for my dissertation. I admit I’m no graphic arts expert, but it gets the idea across:

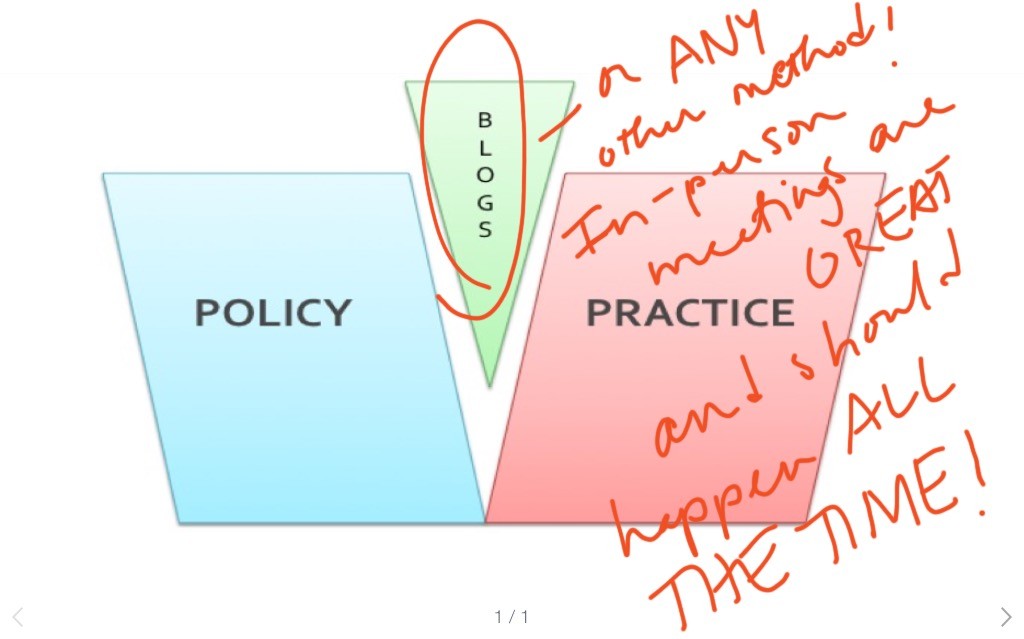

With the development of the Internet, we witnessed unprecedented growth in the ability to publish user-authored content online via blogs and other Web 2.0 tools in the early and mid-2000s. The capability to research and communicate digitally has only improved since. But honestly, it doesn’t matter whether policymakers listen digitally or in person. They just need to listen. The graphic should look more like this:

This meeting a few weeks ago was the first time in my professional life as a teacher (16 years to be exact) that a policymaker asked my opinion about something related to what I do as an educator. The discussion was dynamic. Regent Cashin is a brilliant, sincere individual who I believe is on the right side of the high-stakes testing movement. She hears the call from the opt-out movement. She understands why the rubrics for the edTPA do little to offer specific, genuine feedback. She gets why it’s unfair and inequitable to judge teachers by their students’ test scores. During the meeting, several panels of K-12 teachers, administrators, and local university faculty shared ideas about why implementation of the edTPA isn’t working. And Cashin listened intently, promising to bring our concerns back to her colleagues.

Without more meetings like this, and opportunities for practitioners to share the realities of their daily work, educational policymaking will continue to miss the boat when it comes to changing practice in a systemic, sustainable, effective way.

Comments by