English speakers know auxiliaries as those “helping verbs” they learned about in English class, such as have for perfect aspect (I have eaten), or will for future tense (I will eat), or can to convey permission or ability (He can eat). When you look across languages and start to investigate what makes an auxiliary an auxiliary, you discover a wide range of potential criteria for membership in this category, as drawn from the way the category has been used to describe particular morphology in various languages. I’ll list some of these criteria below, which are taken from a discussion by Heine (1993: 22-24):

• encode tense/aspect/modality

• form a closed set

• occur elsewhere in the language as regular verbs

• neither clearly lexical, nor clearly grammatical

• occur as main verbs elsewhere in the language

• exhibit verbal morphosyntax

• participate in defective paradigms

• are restricted to particular tense/aspect distinctions and/or inflections

• cannot be passivized

• cannot be imperative

• cannot be independently negated

• cannot be the main predicate of their clause

• have free variation between reduced and full forms

• can or must be cliticized

• occur separately from the main verb

• carries all morphological information relating to their predicates

• carries subject agreement

• obligatory in finite clauses

• have “no meaning” on their own

• occur separately from the main verb

• bound to some adjacent element

• may not be nominalized or occur in compounds

• occur in a fixed order and in a fixed position

• associated verb is non-finite

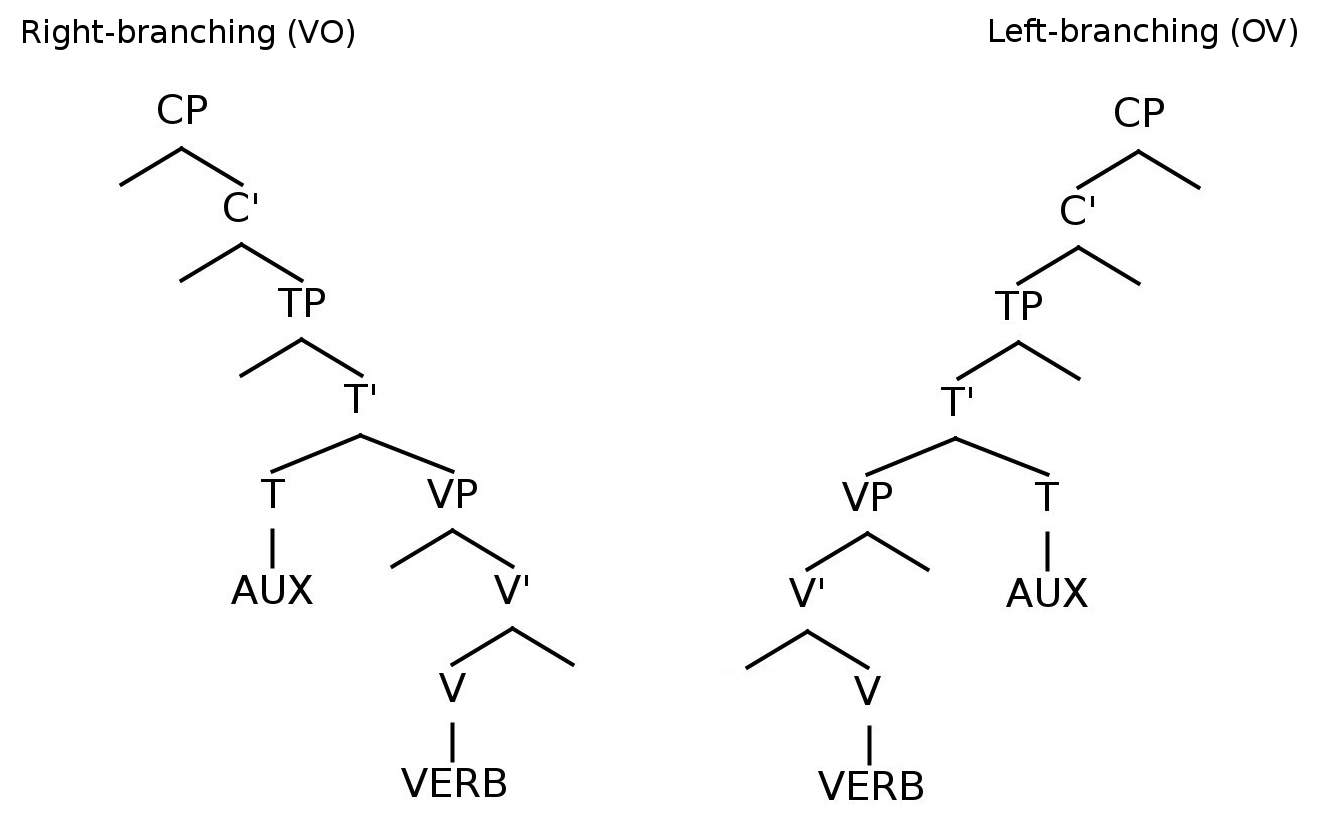

• follow verbs in OV language, and proceed verbs in VO languages

“Auxiliary” is a category used to describe words that have perceived similarities. It is worthwhile to ask what makes members of this category similar, and how this category came to be. How one might go about answering these questions, or even if one would answer the latter question, reveals important information regarding theoretical perspectives in the field of linguistics. Generative grammar, for example, has traditionally treated categories like ‘auxiliary’, ‘verb’, ‘noun’, etc., as “substantive universals” (Chomsky 1965: 28). Questions regarding why such categories exist are not considered useful within generative theory, as they are assumed a priori to be provided by Universal Grammar. On this view, babies are born with these (purely structural) categories in place – the job of the linguist is to discover how these given categories are manipulated relative to one another in generating grammatical sentences, not why or how they exist. Outside of the generative tradition, linguists can be more skeptical of the idea of pre-established structural categories (see, for example, Hasplemath 2007), though this fact is sometimes clouded by the use of similar or identical terminology in generative and non-generative research. When non-generativists use terms like ‘auxiliary’, ‘verb’, and ‘noun’, they include semantic criteria in their definition – universal substance, not universal structure. For generativists, these are strictly structural categories and have no direct relationship to meaning – universal structure, not universal substance. For example, non-generativists may use ‘verb’ to describe a grammatical category that is recurrent across the world’s languages, and is used to denote actions or states. For generativists ‘verb’ references only an abstract structural category, usually labeled V for convenience, but which in principle could be labeled F, 39x, @!, ‘category 1’, or literally anything, since ‘verb’ is not meaningful, but purely structural. An alternate approach would be to consider such recurrent categories in languages to be resultant from how language is used. For example, you could suggest that languages have a category “verb” because actions and states are central to the human experience, and people need to talk about them, and to talk about them often. This doesn’t mean that no structural criteria is included in grammatical categories when they are not provided a priori by theory, just that direct biological endowment of structural properties is not assumed.

Returning to auxiliaries specifically, its important to note what kinds of criteria have been used to define this category. Many of these were listed above. This list was compiled from various language-specific instances where the category ‘auxiliary’ was deemed appropriate by some linguist, though it should be clear that no language will have a category ‘auxiliary’ that meets all these criteria. Why, though, did linguists decide it was appropriate to label particular forms ‘auxiliaries’? Abstracting over these criteria, it seems that ‘auxiliary’ has generally been used to denote forms which encode tense-aspect-modality, occur adjacent to verbs, are separate words, and are verb-like themselves. We can also ask why this category ‘auxiliary’ has the characteristics it does, and why many languages have what might be called ‘auxiliaries’. Again, one approach is to say that the category is universal and built into our theory, but if universal structural categories are not assumed, this kind of “explanation” is unsatisfying. A deeper understanding of the category can be gained by appeal to grammaticalization, a set of parallel processes through which lexical material becomes more grammatical. In grammaticalization, some form which is used with sufficient frequency in particular structural positions gradually becomes semantically bleached, dependent on surrounding grammatical material, and phonetically reduced. Specific morphosyntactic categories have been shown to have semantically similar sources across languages. Movement verbs, for example, tend to be sources for future-marking morphology, and statives tend to be sources for progressive-marking morphology. A study by Bybee (et al. 1994) and colleagues provides a full treatment of such phenomena for TAM morphology generally.

Membership in the category ‘auxiliary’ is not always black and white. The gradience of this category, and others, can be seen in examples where some member is considered aberrant in some way, but nevertheless, remains categorized as such. Take, for example, the Garifuna auxiliary verbs. These words are auxiliary-like in a number of ways: they encode tense-aspect-modality; they occur adjacent to verbs; they form a closed set. It’s not surprising they have been called auxiliaries by those who study Garifuna grammar. However, as has been noted by some linguists (Kaufman 2010, Sheil 2013), the Garifuna auxiliaries are a puzzle because they occur after verbs, even though Garifuna is a VSO language. Greenberg noted in his 16th universal, “In languages with dominant order VSO, an inflected auxiliary always precedes the main verb. In languages with dominant order SOV, an inflected auxiliary always follows the main verb.” Saying this is always the case is overstating the situation, but it has been shown to be a strong statistical tendency (Dryer 1992: 100). Coming from a generative perspective, the question of why Garifuna auxiliaries are placed after verbs is entirely grounded in the synchronic structural properties of Garifuna auxiliaries. The problem under this model is that they come after verbs, but there is no obvious place for them in the tree structure if they are auxiliaries. In generative grammar, auxiliaries have usually been treated as elements that occupy the node T in tree structures, or at least start out there, and include things like auxiliary verbs (AUX) and tense morphology. Below I provide an illustration showing where auxiliaries and verbs are relative to each other in a generative model.

The suggested solution for how to account for Garifuna auxiliaries appearing to the right of the verb within this model has been to treat them like suffixes rather than auxiliary verbs. The Garifuna auxiliaries would then be structurally similar to English tense suffixes, such as -ed, which lower down from the T node to attach at the V node. The problem remains, however, that Garifuna auxiliaries appear to be independent words along several criteria: they are often used with prosodic cues suggesting separate words (though this is not as clear when prefixes are absent), they are written as separate words (suggesting, perhaps, at least a history of being separate words), and most importantly, they can (and do) regularly take prefixes. In fact, Kaufman (2010: 14) takes the position that the major problem with explaining Garifuna auxiliary structure is how to account for these prefixes.

The problem of Garifuna auxiliary placement is different from the perspective that ‘auxiliary’ is not a pre-established category. Instead, the category can be viewed as having come about through typical processes of grammatical change observed across the world’s languages. Auxiliaries prototypically encode tense-aspect-modality, so members will have mostly developed along cross-linguistically observable trajectories of semantic change for TAM morphology (Bybee et al. 1994). Also, since they prototypically occur adjacent to verbs, they will have developed from words that frequently occured adjacent to verbs in their respective languages. Anderson (2006) notes that typical structural sources for auxiliaries are head verbs in verb-verb sequences, which explains the tendency to follow Greenberg’s 16th universal – auxiliaries usually develop from verbs that take verb complements. In my own research (presented at HDLS 11), I have suggested that the Garifuna auxiliaries have been called auxiliaries because they meet typical criteria associated with the auxiliary category, but that they don’t have typical sources for auxiliaries. Because they do not come from head verbs in a verb-verb sequences, they do not maintain the expected pre-verb positioning, hence a VO language with VERB AUX ordering. In carrying out comparative work, I have suggested that the the Garifuna auxiliaries instead have developed from several morphemes that occurred regularly after verbs in the Arawakan family, which explains their atypical ordering.

The example of Garifuna’s auxiliary verbs highlights the gradient nature of the auxiliary category (and others). When a theory employs sharply bounded a priori cagetories, members that are not well-behaved become difficult to account for, and may lead to less than satisfactory explanations (depending on what one counts as explanation). In my view, appeal to grammaticalization processes and comparative-historical work provides a more satisfactory explanation than treating the Garifuna auxiliaries as suffix-like.

Comments by Kevin Hughes