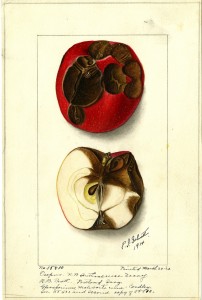

Rendered for the University of California from 1911 to 1915, the pomological water colours of Ellen Isham Schutt (1873-1955) can be read as a progressive era desire for control over nature for the purposes of nation building. In the preceding decade, Schutt had been hired by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) in Washington D.C., to create a catalogue of standards for both foreign and domestic fruit varieties. In 1911 Schutt was poached by the University of California to paint a comparative series on locally farmed apples, grown, harvested and stored under differing conditions, showing a gradation of mould and rot.

These paintings embody a vision of a ‘normal,’ even ‘perfect,’ apple grown in an ideal soil, harvested at the optimal time, and stored at the best temperature to ensure its longevity. But what does a multispecies (Helmreich and Kirkley 2010) interpretation of these paintings look like? Rethinking these images as composites rather than singularities opens up the affective entanglements (Hustak and Myers 2012) of both the human (producer, intended audience) and non-human (apples, bacteria, virus). By the 1930s the use of the newly popularised colour photography techniques in the first plant patents, relegated water colour illustration to the archive of Natural Philosophy. However, I read Schutt’s water colour paintings as more than technologies of standardisation but speculative explorations of the affective via the aesthetic and/or repulsive. By doing a close reading of a few paintings, I think with feminist science studies to complicate the role that these hyperreal images play in the eugenic aspirations of the early twentieth century nation building projects of the USDA.

Comments by xanchacko