This is an excellent description of the International Women’s Network Against Militarism by Gwyn Kirk, one of the founding members.

http://www.feministafrica.org/uploads/File/Issue%2010/profile.pdf

Building Genuine Security: The International Women’s Network Against Militarism

Gwyn Kirk

We are very pleased to have the following description of our Network included in this issue of Feminist Africa because of our concern about the implementation of AFRICOM. We are especially alarmed because Network members have observed and experienced first-hand similar developments and their impacts in Asia, the Pacific, and the US. We also want our African sisters, who face the possibility of new, and perhaps long-term, US military presence on the continent, to know we stand in solidarity with you.

Currently, worldwide, the US military maintains over 700 bases and installations, with facilities and operations on every continent. In addition, there are numerous secret sites, such as those in Israel, or other sites not yet considered official, such as newly established bases in Iraq. The most recent effort at military expansion, the proposed development of AFRICOM or the US Africa Command, is the newest of six regional structures designed to cover particular geographic areas. The other five are the Pacific, Middle East, Europe, South American, and North American commands, each led by a commanding officer responsible for the entire region. The goal is to maintain an integrated network of personnel, equipment, and weapons that can respond at a moment’s notice “to protect US interests,” that is, the interests of capital and ruling elites.

About Us

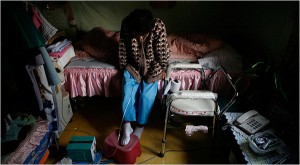

This Network started in 1997 when 40 women activists, policy-makers, researchers, teachers, and university students from South Korea, Okinawa, mainland Japan, the Philippines and the United States gathered to share information and to strategize about the negative effects of US military operations in all our countries. These included military violence against women and girls, the plight of mixed-race Amerasian children abandoned by US military fathers, environmental contamination, and the distortion of local economies. More recently, women from Puerto Rico, Hawaii, and Guam have joined. We have developed a common analysis and understanding of how the US military, directly and indirectly, destroys lives, jeopardizes the physical environment, undermines local economies and cultures, and destroys opportunities to live in sustainable ways. We focus on military institutions, as well as military values, policies, and operations, and their impacts on our communities, especially on women.

The work of the network is significant in several key ways. First, it has brought together women across national, regional, class, race, and linguisticboundaries in a sustained way. Although some of us have met each other at activist and academic conferences, international gatherings such as Beijing Women’s Conference (1995), Hague Appeal for Peace (1999), Tokyo Women’s Military Tribunal (2000), and the World Social Forum (2004), the Network has provided a loose organizational structure and has combined resources to enable participants to meet regularly to exchange information, strategize together, to identify research needs, and to get to know each other personally and politically.

Another importance of the Network is our developing understanding of what is involved in transnational feminist praxis. We are a multi-national, multi-lingual group who subscribe to a range of feminist perspectives. This has both enriched our work and challenged us to think and re-think our collective and individual theoretical understandings of militarism, militarization, military occupation, and armed conflict. Most significant has been examining our relationships to each other while we struggle to resist US militarism and its impacts. Through the decade of our existence, we have faced and addressed, in a variety of ways, issues related to the following questions:

• What does it mean to work across, and in spite of, the asymmetrical structural power relations among us? These include intra-regional inequalities such as among Japanese, Korean and Filipino members, as well as interregional disparities between the US and all other country members.

• How do we address the contradictions and tensions raised by the nature

of these relationships?

• How do we deal with linguistic differences, related to class, ethnicity, culture, so we can communicate effectively as we discuss issues that are intellectual and emotional, and sometimes traumatic?

• What are our collective responsibilities for our respective country’s polices and practices that have impacted others in our Network? This is especially true for US and Japanese participants, whose countries have heavily shaped geopolitical relations historically and contemporarily.

• What do we actually mean by “transnational feminist praxis”?

Key Lessons Learned

We have learned many common-sense and profound lessons during our ten years together. Perhaps the most important is working multilingually. At the first meeting in 1997, we recognized the need for more adequate interpretation and translation among English, Japanese, Korean and Tagalog. This difficulty, and the tensions it generated, still persist. A group of volunteer translators have created a Feminist Activist Dictionary to be used by our interpreters and members, so that we can share common meanings and definitions of words that often cannot be translated directly from one language to another. These include terms such as rape and gender in English, han in Korean, and giri in Japanese. We realise that interpretation and translation take time. Talks and presentations should be finished before a meeting so translators can work on them, for example. Also, we must schedule meeting sessions to allow for interpretation, and identify women who are willing to act as interpreters. As we are not able to pay them for their time, we greatly appreciate the significant, and essential, contribution they make to our work.

One of the most profound lessons deals with privilege and access to resources – both assumed and real-based on race/ethnicity, class, nation, history, and language. One way this has manifested is in relation to money and funding, for example. Sometimes, women outside the US have assumed that US-based women and, to a lesser extent, Japanese women, have easy access to financial resources. Relative to poorer countries, this may be true, but it has not been easy for women living in the US to secure funding for the Network. The nature of work – opposing US military and economic policies and working outside the US – makes it difficult to secure sustained funding from most donors. Occasionally, we have been fortunate enough to secure grants from groups such as the Global Fund for Women. Another problem has been the assumption, by those outside the United States, that US women are a monolithic group. In reality, the US is characterized by serious inequalities based on region, language, race, class, and immigration status. As women living in the US, we have sought to raise awareness about these issues during international Network meetings, including trying to ensure adequate representation of a range of US participants.

Our Vision and Mission

We envision a world of genuine security based on justice, respect for others across national boundaries, and economic planning based on local people’s needs, especially the needs of women and children. Our shared mission is to build and sustain a network of women to promote, model, and protect genuine security in the face of militarism.

Our goals

• To contribute to the creation of societies free of militarism, violence, and all forms of sexual exploitation in order to guarantee the rights of marginalized people, particularly women and children, and to ensure the safety, well-being, and long-term sustainability of all our communities.

• To strengthen our common consciousness and voice by sharing experiences and making connections among militarism, imperialism, and systems of oppression and exploitation based on gender, race, class and nation.

What is Genuine Security?

Security is often thought of as “national security” or “military security”. We believe that militarism undermines everyday security for many people and for the environment. Following the United Nations Development Program report of 1994, we argue that genuine security arises from the following principles:

1. The physical environment must be able to sustain human and natural life;

2. People’s basic needs for food, clothing, shelter, health care, and education must be guaranteed;

3. People’s fundamental human dignity should be honored and cultural identities respected;

4. People and the natural environment should be protected from avoidable harm.

Working for genuine security means:

• Valuing people and having confidence in their potential to live in life-affirming ways;

• Building a strong personal core that enables us to work with “others” across lines of significant difference through honest and open dialogue;

• Respecting differences based on gender, race, and culture, rather than using these attributes to objectify “others” as inferior;

• Relying on spiritual values to make connections with others;

• Creating relationships of care so that children and young people feel needed and gain respect for themselves and each other through meaningful participation in community projects, decision-making, and work;

• Redefining manhood to include nurturing and caring for others. Men’s sense of wellbeing, pride, belonging, competence, and security should come from activities and institutions that are life affirming;

• Valuing cooperation over competition;

• Eliminating gross inequalities of wealth between nations and between people within nations;

• Eliminating oppressions based on gender, race, class, heterosexuality, anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, able body-ism, and other significant differences;

• Building genuine democracy – locally, nationally, regionally, and internationally – with local control of resources and appropriate education to participate fully in decision-making processes;

• Valuing the complex ecological web that sustains human beings and of which we are all a part;

• Ending all forms of colonialism and occupation.

Issues

In our diverse communities we are working on: military violence against women/trafficking, problems arising from the expansion of US military operations, health effects of environmental contamination by preparations for war, and the everyday militarization of all our societies. In the US, low-income communities face aggressive military recruiting and inadequate services due to inflated military budgets at the expense of socially-useful programs. Part of our work is to redefine security, as described above, especially for women, children, and the environment.

Alongside our anti-military critiques, we are working on creating sustainable communities and putting forth our visions of alternatives, sustainable ways to live.

Network Activities vary from country to country and include the provision of services and support to victims/survivors, public education and protest, research, lobbying, litigation, promoting alternative economic development, and networking.

We seek to:

• promote solidarity and healing among the diversity of women affected by militarism and violence;

• integrate our common understandings into our relationships in the Network and in our daily lives;

• promote leadership and self-determination among all the sisters of the Network;

• initiate and support local and international efforts against militarism;

• strengthen our work by exploring our diverse historical, social, political, and economic experiences in each nation/country.

Together, we address the challenge of how to link these separate efforts, each focusing on small parts of the military system. We do it in the following ways:

• International meetings

• Facilitating links among country groups

• Coordinated activities

• Supporting each others’ individual activities and campaigns through letters, donations, selling goods

• Educating people in our communities about how US militarism impacts women, children, and the environment in other countries of the Network

• Writing, talks and presentations

Network participants have organised 6 international meetings in:

Okinawa (1997 and 2000)

South Korea (2002)

Philippines (2004)

United States (1998 and 2007)

These meetings include site visits to US bases and women’s projects, public sessions to share information and perspectives, internal discussions of the issues women are working on in each nation, art-related and cultural activity, and media work.

Network members have also participated in other international efforts:

Hague Appeal for Peace (1999)

Grassroots Summit for Bases Cleanup (1999)

World Social Forum (2004)

Our expertise

• Knowledge. We know how US militarism impacts communities in the Asia/Pacific region and the Caribbean as well as in the United States.

• Analysis. We see important connections and continuities between US domestic and foreign policy that link communities impacted by military decisions, budgets, and operations in the US and abroad. We use the lenses of gender, race, class and nation to analyze the issues.

• Solidarity. Our Network comprises veteran organizers and relative newcomers. We have sustained this Network for 10 years across geographical distances, differences of language and culture, and complex histories among our nations.

• Languages. At the Network level we decided not to work only in English. This would limit participation to women with college education, whereas many activists who are doing cutting edge work are not fluent in English. Currently, the Network works in 5 languages: English, Japanese, Korean, Spanish and Pilipino. We have dedicated interpreters/translators who facilitate clear communication. They have compiled a dictionary of over 400 terms that need precise, systematic translation.

• Organizing and Leadership Development. The country groups all involve skilled and experienced organizers working in their communities on these issues. The international meetings have been extremely effective in supporting this local organizing and creating opportunities for younger activists to develop leadership skills and experience.

• Public education. Many Network participants give talks and workshops, and publish popular articles, op ed pieces, and more scholarly papers.

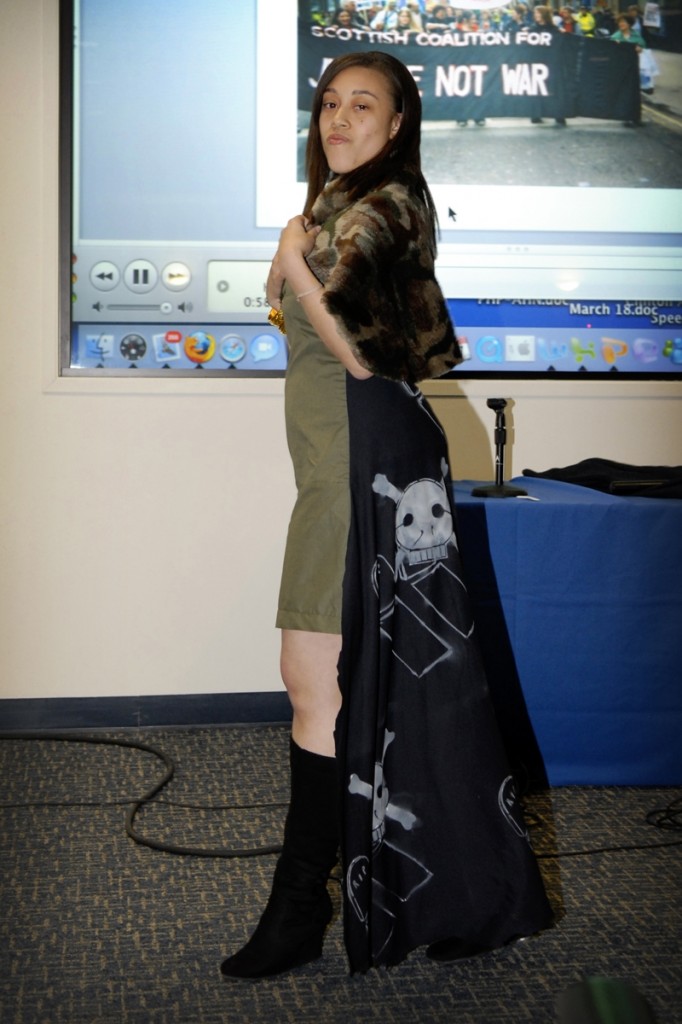

• Art and social change. Network participants include visual artists, poets, writers, dancers, and performers. We see a crucial connection between the arts and action for social change.

Future growth involves:

• Better communication among our country groups;

• Deeper understanding of the issues and how to address them;

• More country-country connections and activities;

• More Network-wide activities;

• Expanding the Network by adding more country groups and linking with other women’s anti-military networks;

• Being able to support a Network secretariat, possibly with paid staff time.

International partners include women active with:

Asia Peace Alliance, Tokyo.

Japan Coalition on the US Military Bases, Yufuin, Oita.

Okinawa Women Act Against Military Violence, Naha, Okinawa.

Du Rae Bang (My Sister’s Place), Uijongbu, South Korea.

National Campaign to Eradicate Crime by US Troops in Korea, Seoul.

SAFE Korea, Seoul.

BUKLOD Center, Olongapo City, Philippines.

Philippines Women’s Network for Peace and Security, Manila.

WEDPRO (Women’s Education, Development, Productivity and Research

Organization) Quezon City, Philippines.

Institute for Latino Empowerment, Caguas, Puerto Rico.

Alianza de Mujeres Viequenses, Vieques, Puerto Rico.

DMZ-Aloha A’ina, Hawaii.

Nasion Chamoru, Guam

Women for Genuine Security is the US-based Network group with members in the San Francisco Bay Area, Los Angeles, and Seattle. US partners include women active with Bay Area groups: AFSC, babae, FACES, KAWAN, PANA Institute, Women of Color Resource Center, and Women’s International League for Peace & Freedom.

We are among the Network founders and have several distinct roles within it:

• Transnational collaborative work with women outside the United States – e.g. educating US audiences about the US military presence in the Asia-Pacific region and the Caribbean, and writing letters to officials (in the US and outside) in support of local activism in Network nations.

• Working with US groups concerning the effects of militarism in the United States and bringing this perspective to the international Network.

• Fundraising to support travel and accommodation at international meetings for women from poorer countries.

• Providing informal co-ordination for the Network.

As women living in the United States, our model of transnational organizing means taking into account the unequal power relationships between the US and the countries where US bases are located. Taking our national privilege seriously, we strive to create working relationships that are equal, mutually respectful and democratic, between women across nations. We seek to avoid recreating the same power hierarchy among us as exists between our nations.

We want to work with women who are doing grassroots organizing, which means that translation and interpretation are key components of our work. This international network includes strong friendships that have been sustained for over a decade. We believe that working together is possible despite language difference, cultural differences, and geographic distance because we have forged strong personal relationships, not just based on the issues we care about, but by really hearing and sharing each others’ passions, life stories, and commitments.

Our international meetings last from 4-7 days to allow time for translation, and the cultural sharing that grounds our relationships and commitments to one another’s struggles and to our work together. We also build our connections through country-to-country exchanges of women activists visiting each other for consultation, study, speaking tours, research, and shared inspiration.

For more details see www.genuinesecurity.org

This website started out with a focus on Women for Genuine Security. We plan to expand it to become more international in scope.

Contact us at info@genuinesecurity.org