Washed ashore

Keith Bettinger

Apr 11, 2007

It’s a refrain that has become frighteningly familiar: Relics of a long forgotten military operation turn up where they aren’t supposed to be, causing alarm in the community. An often frustrating and fruitless quest for answers follows, further straining the relationship between the civilian population of Hawai’i and its military tenants. This time the area in question is Ordnance Reef off of Poka’i Bay, and the relics in question are small, fibrous pellets that burn intensely when exposed to open flame. These tiny pellets are reportedly igniters for large artillery rounds and rockets left over from World War II.

According to reports in the local press, Army officials claim that ordnance dumped less than a mile from shore is not a threat to the fish and other marine life that inhabit the reef. The Army also stated that the dump does not pose a danger to the people who eat the fish around the reef or who swim in its waters.

Wai’anae residents believe differently. For them, the coast is not clear.

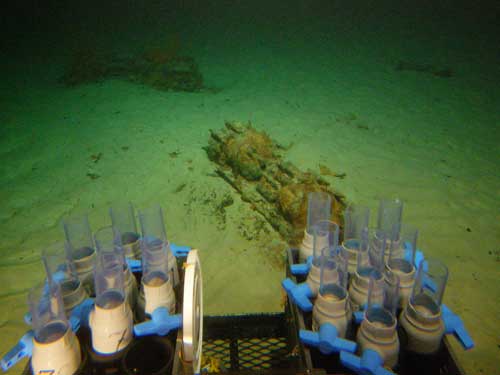

In May 2006, the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) conducted a survey of the ordnance site off Wai’anae. The study was part of the Ordnance Reef Project, which was under the direction of the Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Army for Environment, Safety and Occupational Health. The study employed biological, sediment and water sampling. It indicates that overall trace metals in sediments are very low and that there is little evidence of contamination of the area from discarded munitions.

But questions and concerns remain. Why? Technically speaking, the headlines of a few weeks proclaiming that it’s all clear off the Wai’anae Coast are wrong.

According to Michael Overfield, marine archaeologist with NOAA and coauthor of the report, it is a jump to say that the report concluded the reef is safe. The Army’s Office for Munitions and Chemical Matters made that conclusion, not NOAA.

‘I personally have seen grenades, grenade cans and grenade pins in 80 feet of water…I’ve got [a grenade pin] sitting on my desk’

-Waianae harbormaster William Aila

Erroneous conclusions aside, others believe the report itself is flawed. William Aila, Jr., longtime Wai’anae harbormaster, takes issue with the methodology used in analyzing the fish. He explains that the analysis didn’t target specific parts of the fish (i.e. organs) where metals or contaminants might accumulate. Instead, technicians ‘homogenized’ the fish, blending its parts together.

Others complain that the fish that were analyzed are not the kinds of fish that people eat (one of the objectives of the study was to collect fish species that are ‘harvested for human consumption’). Although the moano, the main fish taken from the Ordnance Reef area is a common food, Aila and others argue that there would be better choices.

‘The moano eats above the sand. It doesn’t eat the algae from the coral,’ the harbormaster says. ‘They should have picked a fish that people eat that are close to the coral. Those other fish [malamalama, humuhumu mimi, maka’a] are not fish that people eat.’

Aila speculates that the moano was chosen because that is the only fish researchers could catch.

Overfield points out that the choice of fish was determined by NOAA. He adds, ‘Unfortunately with fish, they don’t volunteer themselves to jump on your spear.’

Residents present at a Wai’anae neighborhood also questioned why there are so few fish swimming around the reef; these questions seemed to contradict comments made by one of the NOAA report’s coauthors to a briefing that the area was ‘teeming with life.’

Overfield says, ‘I saw a lot of reef fish down there. I saw a lot of coral growth as well. Coming out of Pˆka’i Bay to where there were large concentrations of munitions×We saw a lot of coral.’

However, one divemaster present at the meeting said quite pointedly, ‘That reef is dead.’

Uncovering the source

Sometime in the early 1920s the Army started dumping munitions at sea. These dumps included tremendous amounts of captured and unused chemical weapons. Around 64 million pounds of nerve and mustard agents along with 500 tons of radioactive waste are documented; the actual total including undocumented dumpings and dumpings for which records have been lost are likely higher.

‘They should have picked a fish that people eat that are close to the coral. Those other fish are not fish that people eat’

-William Aila

This activity continued until 1970, when public concerns prompted Congress to prohibit the practice. Now the Army is working to chronicle the history of chemical weapons dumping in an effort to see if there is any potential danger.

In a public study released in 2001, the Army’s Historical Research and Response Team identified 26 sites around the globe where the armed forces disposed of chemical agents in the ocean between World War II and 1970. (Other older sites are likely; the dumping of chemical weapons was common after World War I.) The report documents three sites in Hawai’i.

The first site was off Wai’anae, and the dump was made in late 1945. The report states that material was loaded at Wai’anae ‘to avoid moving the munitions through densely populated areas’ and that ‘the exact location of the sea disposal is unknown.’ This incident included over 4,000 tons of chemicals munitions, including hydrogen cyanide bombs, cyanogens chloride bombs, mustard bombs and lewisite.

The second dump occurred in 1944 off Pearl Harbor and included 4,220 tons of ‘unspecified toxics [sic] [and] hydrogen cyanide.’ The report notes that this material was probably loosely dumped and speculates that this is likely the source of a mortal round that injured a dredging crew in 1976.

The third documented dump occurred in 1944 ‘about five miles off of O’ahu’ and included around 16,000 100-pound mustard bombs or around 8,000 tons of chemical munitions. No one seems to know where this dumpsite is.

Although ‘the exact location is unknown,’ the Army knows where the chemical weapons should be. According to Department of War directives in effect in 1944, disposal sites were required to be at least 300 feet deep and 10 miles from the shore. In 1945 the policy was revised, changing the depth requirement to 600 feet. The policy was revised again in 1946, requiring a 6,000 foot depth for chemicals and 3,000 feet for explosive ammunition.

It is clear that the records don’t match regulations. It is also clear from other reports that munitions are often not where they are supposed to be-more are probably in places nobody has thought to look.

Currently, the Department of Defense is putting the finishing touches on a more comprehensive report covering ocean chemical weapons sites. It is expected to be released in the next month or so.

And while this new report will lead to more questions being asked and an increase in the number of folks calling for a cleanup, for now, though, there are more immediate problems lurking just off shore.

Hawaiian Jade

The munitions at Wai’anae have been found much closer than 10 miles from shore. The so-called Ordnance Reef or 5-Inch Reef (named for the presence of large, 5-inch diameter shells) ranges from .3 to 1.2 miles offshore. According to Aila, munitions have been found right off the Poka’i Bay break wall, less than 50 yards off shore at a location known to divers as Ammo Reef. Moreover, the previously mentioned cigarette-filter-size flammable nodules that have been described as ‘nitrocellulose propellant charges’ have been washing up on the shore for more than 50 years.

‘Another homeless person told me that these tablets are what we used to use to start bonfires. I lit it with a lighter and the thing just shot off. I blew it out and it restarted again by itself.’

-Alice Greenwood

‘We’ve found full-on artillery shells,’ says Aila, who has called the Navy’s Explosive Ordinance Disposal Unit twice over the past 20 years. ‘I personally have seen grenades, grenade cans and grenade pins in 80 feet of water. I’ve got one sitting on my desk.’

Aila explains that there is probably ordnance he doesn’t know about: ‘Often times people don’t tell me because it’s an interesting dive site, and they don’t want me to have the ordnance removed.’

The report and the munitions were on the April 3 meeting agenda for the Wai’anae Neighborhood Board No. 24. During the meeting board member Paul K. Pomaikai said, ‘Tonight I’m going to make an action to set a date to start the cleanup. I say that we take it all the way to Washington, D.C.’

He adds, ‘When it hits the tourists in Waikiki, then we do something? We don’t know what else is going to wash up. The stuff that doesn’t wash up is what worries me. The stuff that gets in our coral and in our fishes.’

That night the board passed a motion to ‘demand the military clean up the reef, shore and ocean starting June 1, 2007, in Wai’anae.’

According to observers, the board was uncharacteristically unanimous regarding this issue. ‘There are some real pro-military people on that board,’ says Fred Dodge, a local physician and activist familiar with the issue. ‘The fact that they went along with the motion shows how united they are on this.’

Alice Greenwood, a lifelong resident of Wai’anae, says she first learned of the pellets from the beach’s homeless residents.

“Look, this is ‘Hawaiian Jade”, [the homeless person] told me. I took the tablet and showed it around. Another homeless person told me that these tablets are what [they] used to use to start bonfires,’ she says. ‘I lit it with a lighter, and the thing just shot off. I blew it out, and it restarted again by itself.’

Greenwood was in attendance at the neighborhood board meeting. She presented one of the igniters to the Navy representative who was on hand for the monthly briefing. She requested the representative take the igniter for testing.

According to Greenwood, ‘When the ocean is calm, not many wash up. The ocean is getting rougher now, though, so we’ll probably see a bunch wash up in the next few days.’ She says she has a ‘whole jar’ filled with igniters ranging in size from one to three inches in length and she regularly collects them from the beach’s residents.

The bombs from wars past that make up Wai’anae’s explosive tide are not the same types of munitions detailed in the Army Historical Team’s 2001 report. In fact, they don’t seem to be chemical weapons at all, but are rather conventional munitions; military dives in 2002 revealed a variety of munitions including naval gun ammunition, 105mm and 155mm artillery projectiles, mines, mortars and small arms ammunition. So the question is, where did they come from? Again, no one seems to know.

The best guess is that the munitions were dumped during World War II, but there is no way to know for certain. And the lack of documentation indicates that there is no way to know the extent of the dumping zone or if other dumping zones exist elsewhere around the islands.

Furthermore, the study states that the survey found nine additional clusters of military munitions not previously identified near the shore, suggesting that there may be other discarded military munitions waiting to be discovered. But the NOAA report also indicates that levels of metals (except copper) in fish seem to be normal and no positive relationships between the ordnance and heightened levels of contaminants could be ascertained.

So is the Wai’anae issue closed? Probably not, but it’s going to be an uphill slog for community activists and legislators looking for answers and pressing for action.

J.C. King, an assistant for munitions and chemical matters for the Army says the study shows ‘there is no immediate threat to the public or the environment’ and that no cleanup is imminent.

Some locals don’t agree with that assessment. ‘What if children find those [propellants]?’ asked one resident present at the meeting. ‘They are washing up all over the place.’

‘Insead of someone who’s from outside the community, they should have someone who’s from Waianae doing the study. They should talk to the people who are at the beach all the time’

-Rep. Maile Shimabukuro

Rep. Maile Shimabukuro, who represents Wai’anae, is less than satisfied with the results of the study. ‘Instead of someone who’s from outside the community, they should have someone who’s from Wai’anae doing the study. They should talk to the people who are at the beach all the time. There seems to be a disconnect between the locals and the people doing the study,’ she says. ‘And they should’ve tested humans×People that are in the water almost every day.’

Rep. Shimabukuro has filed several Freedom of Information Act requests for documents pertaining to the Wai’anae dumpsite. So far her office has not received a substantive response.

‘There is a pattern of obstructionism, denial and not listening to the community. They are control freaks about any bit of information that comes out,’ says Aila of his interactions with the military. ‘They know that they’re in a situation where they can deny and deny until we come up with undeniable evidence and proof, and then they attempt to minimize that proof. It’s a classic pattern.’

It’s a difficult situation with no clear solution in site. A cleanup would cost millions and would damage the reef. Furthermore, given the fact that there are no records, there could be other sites around the island. The military has to consider how much it wants to put itself on the hook for.

Although Army spokesman Troy Griffen previously assured Wai’anae residents that ‘[the Army] accepts responsibility for those propellant grains as a military cleanup issue, and we’re working diligently and urgently with other agencies to determine the next actions that need to be taken,’ the Army says the new study indicates that no cleanup is necessary.

While there is no way to know where the next munitions will wash up, what is certain is that they eventually will. Or they will leak out of their containers. Or they will roll around on the ocean floor, damaging the coral. Or they will be dredged up by unsuspecting fishermen. Denying the problem only makes it worse.

According to many residents, community activists and politicians, the military is not always forthcoming when confronted with the lingering remnants of their past activities. There are complaints of willful obfuscation, misinformation and foot dragging. Only when the truth starts to come out, activists say, does the military ‘goes into damage control mode.’

As a result, many locals say that until the military adopts an attitude of willingness to clean up after itself, they will continue to feel unsure about the fish they eat and the water they swim in.

Army officials did not respond to numerous requests for information for this article.�

Keith Bettinger can be contacted at kisu1492@yahoo.com.

What is the danger of submerged chemical weapons?

Until the ocean disposal of chemical weapons ceased in 1970, the military dumped millions of pounds of chemicals into the seas. Exact amounts and precise locations are unknown, but according to Craig Williams of the Kentucky-based Chemical Weapons Working Group, more than 500,000 tons has been dumped off U.S. coasts, including Hawai’i. The theory behind dumping chemical weapons in the ocean is that they will dissipate before causing any serious damage or that the pressure and cold temperatures of the depths of the ocean will render munitions inert. However, containers corrode over time, releasing the chemicals into the ocean. The longer the chemicals remain in the ocean, the greater the chances for a rupture or leak.

‘There are a number of avenues of risk associated with this,’ Williams says. ‘The highest is to marine life. In small doses chemicals can accumulate in animals and work their way up the food chain×There are also impacts on the reproductive capabilities of some species, in addition to the lethality of higher doses.’

Though military documents indicate these chemicals break down quickly in water, they can remain dangerous in their containers for years. And military studies might be misleading.

‘Some studies contradict this blanket feel-good position of the government. Each chemical agent will have a different reaction with whatever it is exposed to, whether it is water or salt water. It is inappropriate of the government to assume that chemicals will react the same way and dissipate,’ Williams adds.

Here are details of some of the known chemical munitions dumped off the Hawaiian Islands. Army records also indicate numerous other dump locations in unspecified areas around the Pacific Ocean.

Mustard 3,927 tons

These are blister agents that form a solid mass in the colder temperatures fond at ocean depths. They are heavier than seawater and not very water soluble. According to Army documents, mustard deteriorates due to hydrolysis into chemicals (thiodiglycol and hydrochloric acid) that are non-toxic or are neutralized by the seawater. However, as the mustard deteriorates a hard polymer shell develops, effectively sealing the mustard off from the seawater. Thus mustard can remain stable for years in the ocean. ‘If a mustard round or container were to rupture or begin leaking, the evidence suggests the water encapsulates the mustard that is leaking into a globular underwater oil slick that can travel significant distances before it is broken up by current or topography,’ explains Williams. This is what caused large pus-filled blisters to afflict a bomb disposal crew from Dover Air Force base called in to dispose of mustard pulled up by a dredging operation in New Jersey in 2004. A similar incident occurred here in 1976.

Lewisite 399 tons

Lewisite is a blister agent similar to mustard, but faster acting. It is denser than mustard and has a much lower melting point, so it is usually in the form of a liquid in the ocean. When it was originally manufactured (production ceased in 1943) other chemicals were added as stabilizers, and so about a third of lewisite is actually arsenic. Army bulletins say that lewisite quickly loses its blister agent properties when exposed to seawater, but during this process arsenic is released, thus resulting in increased arsenic concentrations in sediments or solution.

Hydrogen Cyanide 4,227 tons

This toxin works by preventing the body’s cells from using oxygen. According to Army bulletins, this chemical, which was used mainly in World War I, quickly breaks down in seawater.

Cyanogen Chloride 489 tons

CK, as this agent is also known, is a colorless gas which is unstable in canister munitions and can form explosive polymers. CK is very soluble in water and breaks down quickly, and through a chain of reactions eventually yields carbon dioxide and ammonium chloride.

Source: http://honoluluweekly.com/cover/2007/04/washed-ashore/