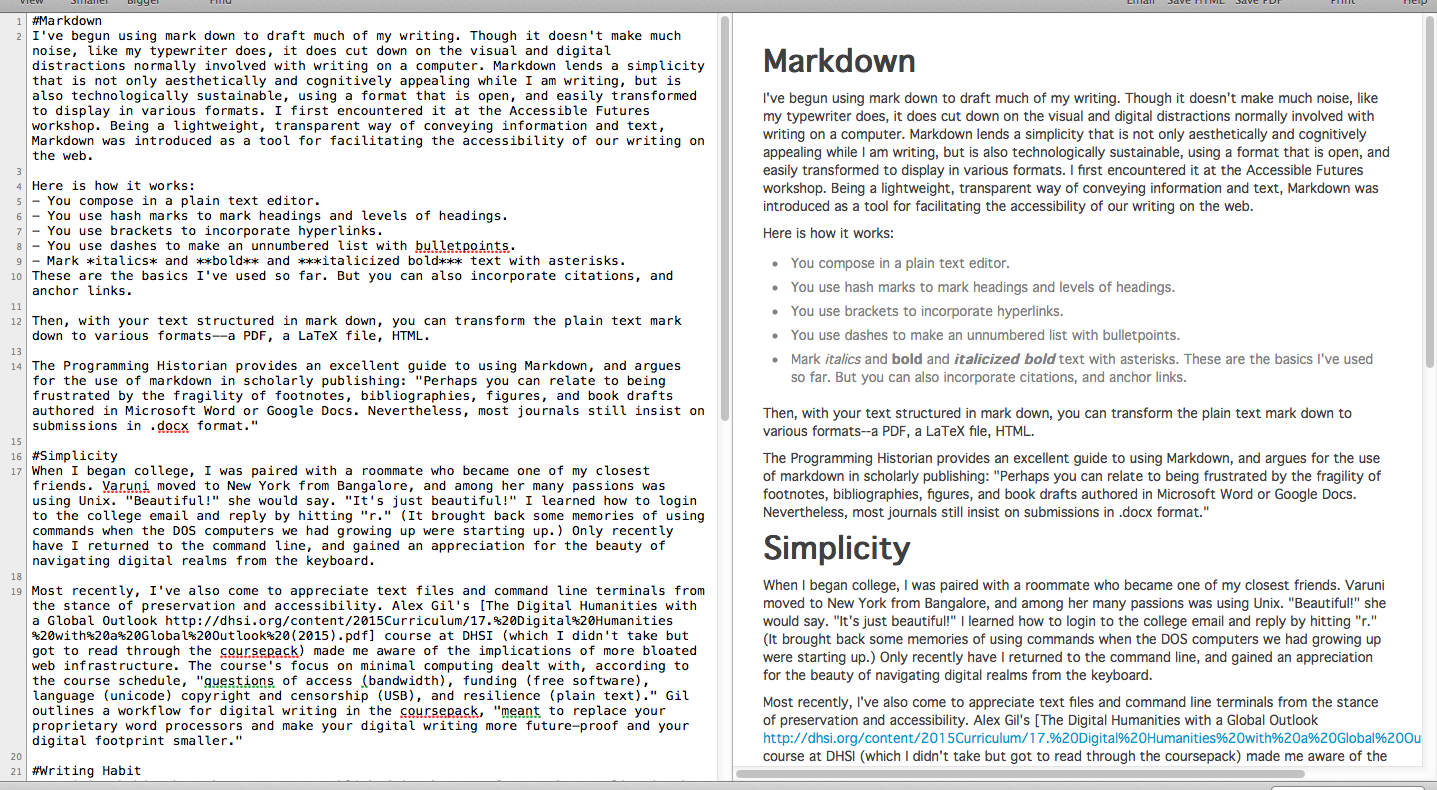

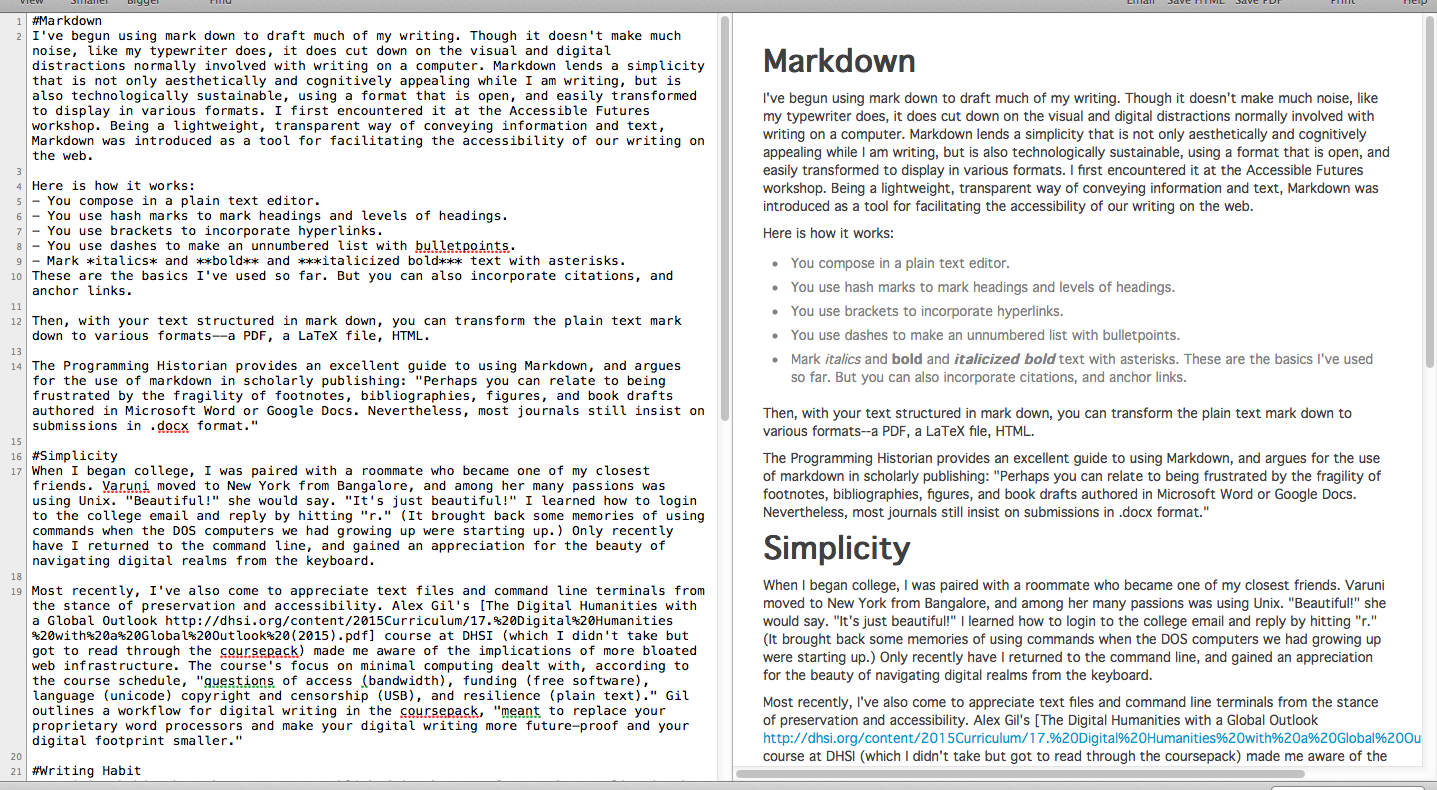

Markdown

I’ve begun using Markdown to draft much of my writing. Though it doesn’t make much noise, like my typewriter does, it does cut down on the visual and digital distractions normally involved with writing on a computer. Markdown lends a simplicity that is not only aesthetically and cognitively appealing while I am writing, but is also technologically sustainable, using a format that is open, and easily transformed to display in various formats. I first encountered it at the Accessible Futures workshop. Being a lightweight, transparent way of structuring information and text, Markdown was introduced as a tool for facilitating the accessibility of our writing on the web.

Here is how it works:

- You compose in a plain text editor.

- You use hash marks to mark headings and levels of headings.

- For instance: #Heading1; ##Heading2.

- You use brackets to incorporate hyperlinks.

- [A link to this post](annedonlon.org/markdown) would appear as A link to this post

- You use dashes to make an unnumbered list with bulletpoints.

- – Like so.

- Mark italics and bold and italicized bold text with asterisks.

- *italics* and **bold** and ***italicized bold***

These are the basics I’ve used so far. But you can also incorporate citations, and anchor links.

With your text structured in mark down, you can transform the plain text mark down to various formats–a PDF, a LaTeX file, HTML, defining the specific formatting of each of these different elements (the size and font of headings; the color of a hyperlink) in a stylesheet.

The Programming Historian provides an excellent guide to using Markdown, and argues for the adoption of markdown in scholarly publishing:

Perhaps you can relate to being frustrated by the fragility of footnotes, bibliographies, figures, and book drafts authored in Microsoft Word or Google Docs. Nevertheless, most journals still insist on submissions in .docx format.

Markdown makes these structural elements transparently visible, easily transported across formats.

Simplicity

When I began college, I was paired with a roommate who became one of my closest friends. Varuni moved to New York from Bangalore, and among her many passions was using Unix. “It’s just beautiful!” she would say, admiring its simple functionality. Elegant math proofs were another realm that would elicit such praise from her. She taught me how to log in to the college email and reply by hitting “r.” (It brought back some memories of using commands when starting up the DOS computers we had when I was a kid.) Only recently have I returned to the command line, and gained an appreciation for the beauty of navigating digital realms from the keyboard.

I’ve also come to appreciate text files and command line terminals from the stance of preservation and accessibility. Alex Gil’s The Digital Humanities with a Global Outlook course at DHSI (which I didn’t take but brushed up against while at UVic this summer, and have read through the coursepack) made me aware of the implications of more heavyweight web infrastructure. The course’s focus on minimal computing dealt with “questions of access (bandwidth), funding (free software), language (unicode) copyright and censorship (USB), and resilience (plain text).” Gil outlines a workflow for digital writing “meant to replace your proprietary word processors and make your digital writing more future-proof and your digital footprint smaller.”

Writing Habit

My writing habits have become more established in the past few months. Earlier in the year, I mentioned wanting to “fail faster” at waking up early to write before going to work. I liked the idea of writing before the bustle of the day got underway, and I have never been good at writing in the evenings, but for a while, the appeal of the snooze button won out. I’m not certain what made the change happen, but I have had success waking up early to write on weekdays this spring and summer. At some point, the fact that I was getting up and getting work done became reward and motivation unto itself.

I use “pomodoros” to structure the time–at least that is when my morning writing feels best. I get up, put the kettle on, and work in the living room with a cup of tea for twenty-five minutes. Then, when the timer goes off for the five minute break, I do a few body weight exercises. I have a book a former running buddy recommended to me, You Are Your Own Gym. I’m fascinated by the book’s paratext. The introduction explains that the author designed these exercise regimes in the context of the military, post-September 11th, 2001, when suddenly the military needed many more individuals to pass elite fitness entrance exams. They needed to completely overhaul the way they were training people ahead of the exam to get them fit much quicker, and the exercises regimes outlined in the book were the answer. My ambivalence about adopting this post-9/11, imperialist, militaristic regimen has not been enough to abandon the book, though. (Hence, the fascination; how do fitness regimes and bodily discipline order the political world I contribute to? How to understand the complicity across these realms?) Anyway, when the timer goes off and my break starts, I do a round of exercises–modified pullups on a broomstick laid across to bar chairs, “Bulgarian split squats,” “Russian twists,” lunges, push-ups off the kitchen counter, dips from the living room loveseat. I hope someone smarter than me will write or has written something about the Cold War and the endless war contexts of fitness exercises.

At some point before or after the exercise, I arrange some breakfast–putting some oatmeal on the stove, or throwing some combination of fruit and yogurt and seeds into the blender. Then, if I’m still on schedule, I settle in for round two. Depending on the time, I may skip the second round of exercises in the break period, but if I’ve made it this far, I already feel pretty accomplished for the day.

I’ve had success the past few months working this way. I got a revised article back to a journal; a revised chapter back to an editor; a draft of a new teaching statement put together; lots of notes and comments toward a draft of something new onto a google doc shared with my collaborator, Evelyn.

Writing with Markdown and writing at the beginning of the day have worked well for me.

Now I need to get back to my typewriter for afternoon writing (of a more recreational variety–letters, and my forthcoming TEI zine). And I got another desktop machine around the same time I got my typewriter–a sewing machine–which I am eager to get more into the habit of using, too. (I’ve got grand plans for a quilt.)

The gendered histories of these technologies resonate through the history of computing. (See, for instance, Roxanne Shirazi’s Reproducing the Academy: Librarians and the Question of Service in the Digital Humanities, this interview with Margaret Hamilton, and Jennifer S. Light’s “When Computers Were Women,” in the Journal for the Society for the History of Technology.) I’m curious to see if working on these analog devices (do sewing machines and typewriters count as analog, technically?) change my relationship to making and writing in digital realms. The transparency of Markdown provides a sense of hands-on, pared-down control over the making of a text.

Dominique

Anne, everything about this post is inspiring — love the purposeful weaving of the personal, the instructive, and the historical/technological meta-reflection. I have one month until I start teaching again — think that’s enough time to develop/re-discover some of these good habits?

Write on!

Dominique