Emily Holloway

I’ve been fiercely protective of New York City since moving here three years ago. Yes, I know New York doesn’t need my protection – it’s doing just fine, thank you very much. Nonetheless, I express my solidarity with New York every day, rolling my eyes at newly-built generic condo developments, grimacing when another branch of Chop’t opens but Carnegie Deli closes, and shaking my head at the bland public spaces our estimable city planners have designed for the postindustrial milieu. These are common rituals, part of being a New Yorker and thus part of wanting to be a New Yorker. I’m not really a New Yorker yet; three years still isn’t ten years, that oft-cited metric of nativity. But when change occurs as rapidly and as enormously as it does in this city, it’s hard not to feel like you’ve been a part of it forever.

Exactly one month before Amazon announced it would cancel its plans to open HQ2 in Long Island City, Queens, I wrote an article for this publication outlining the democratic deficiencies of New York’s economic development processes that had enabled the original plan. I had hoped to focus attention on the (legal) long-standing incumbent tax and development loopholes that make public review irrelevant to policymakers and businesses. Bureaucracy is a bore, but the devil lies in the details: Industrial and Commercial Incentive Programs (ICAP), Trump’s Opportunity Zone (OZ) program, the Excelsior Jobs Program, the Relocation and Employment Assistance Program (REAP), Payment in Lieu of Taxes (PILOT)…a veritable alphabet soup of anodyne acronyms and inscrutable finance law text. This providential constellation of available incentives added up to a tax incentive of over $3 billion in tax expenditures for the global corporate giant with a gross valuation of $1 trillion. Small change for Amazon, perhaps, but a meaningful share of New York City and State’s budgets.

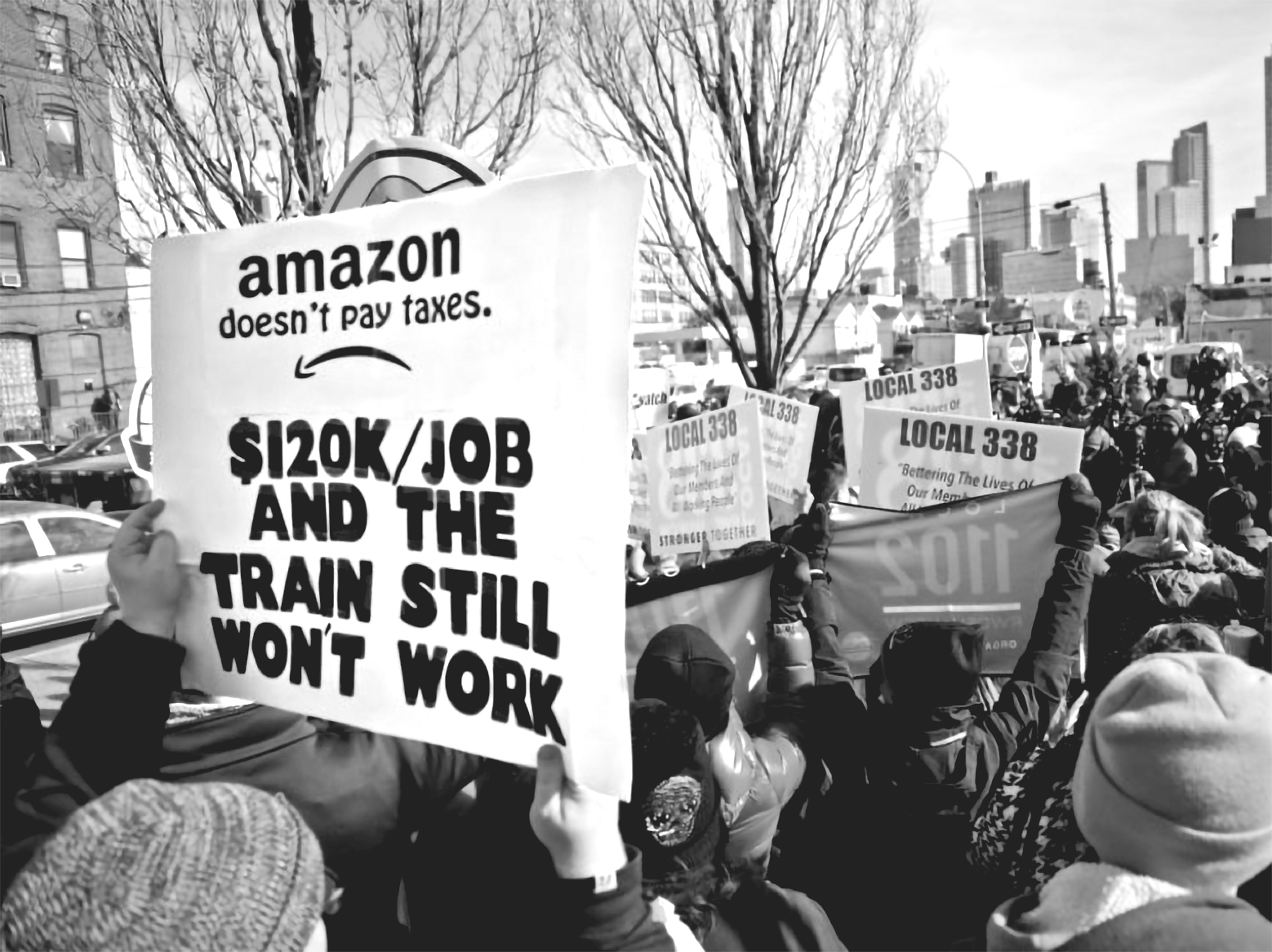

Unless you’ve been in a coma, or maybe orbiting in outer space beyond the reach of social media, you probably heard the November announcement that Amazon would locate half of its HQ2 in Queens. You probably also heard about the protests, the City Council hearings, the op-eds decrying the deal. You also saw a rare instance of executive comity between Governor Andrew Cuomo and Mayor Bill de Blasio, who commissioned their (non-elected) economic development agencies to facilitate negotiations with Amazon, conduct cost-benefit analyses, and mark out the real estate for Jeff Bezos’s helipad on the East River shore.

And unless that coma persisted until February 15th or your space rover is still making its way back from Mars, you have probably also heard that Amazon decided New York City was more trouble than it was worth. Despite New York’s “incomparable dynamism, people, and culture,” opposition to the corporation was just too fierce. Many of us were surprised by the level of taxpayer-provided support offered to the company last year. All of us were surprised that it wasn’t enough. Amazon’s decision will be dissected for months to come, perhaps years. Depending on the course of history, it will be celebrated or lamented. Will New York’s economy fall behind other cities? If the economy and employment opportunities are not revolutionized to keep pace with innovation, what will become of our great city? Beyond the market-driven handwringing, however, is an alternative story, the one that actually reflects New York’s inheritance of democratic protest, worker’s rights, and diverse and meaningful political participation. Because regardless of which history will win out in the end, the past three months demonstrates that those impulses have not quieted, that resistance is not irrelevant.

And unless that coma persisted until February 15th or your space rover is still making its way back from Mars, you have probably also heard that Amazon decided New York City was more trouble than it was worth. Despite New York’s “incomparable dynamism, people, and culture,” opposition to the corporation was just too fierce. Many of us were surprised by the level of taxpayer-provided support offered to the company last year. All of us were surprised that it wasn’t enough. Amazon’s decision will be dissected for months to come, perhaps years. Depending on the course of history, it will be celebrated or lamented. Will New York’s economy fall behind other cities? If the economy and employment opportunities are not revolutionized to keep pace with innovation, what will become of our great city? Beyond the market-driven handwringing, however, is an alternative story, the one that actually reflects New York’s inheritance of democratic protest, worker’s rights, and diverse and meaningful political participation. Because regardless of which history will win out in the end, the past three months demonstrates that those impulses have not quieted, that resistance is not irrelevant.

This isn’t the first mega-development proposal to be thwarted by New Yorkers. Even Robert Moses, perhaps the most adept and canny circumventer of democratic processes in our history, has been shut down. A legendary showdown between Moses and Jane Jacobs sealed the fate of the Lower Manhattan Expressway in the 1960s. Mayor Bloomberg’s push for the 2012 Olympics on the West Side of Manhattan failed (although the development did morph into the current Hudson Yards mega-project), as did his development proposal to convert the historic Kingsbridge Armory in the Bronx into a shopping mall. Sure, the list of contentious and problematic development projects that were approved far outstrips the number of those defeated – Hudson Yards, Atlantic Yards, the Cross-Bronx Expressway, the rezoning of North Brooklyn, the construction of the United Nations building, to name just a handful – but none of these had the visibility, the urgency, the cross-coalition, cross-borough, cross-class, cross-jurisdictional singularity of HQ2.

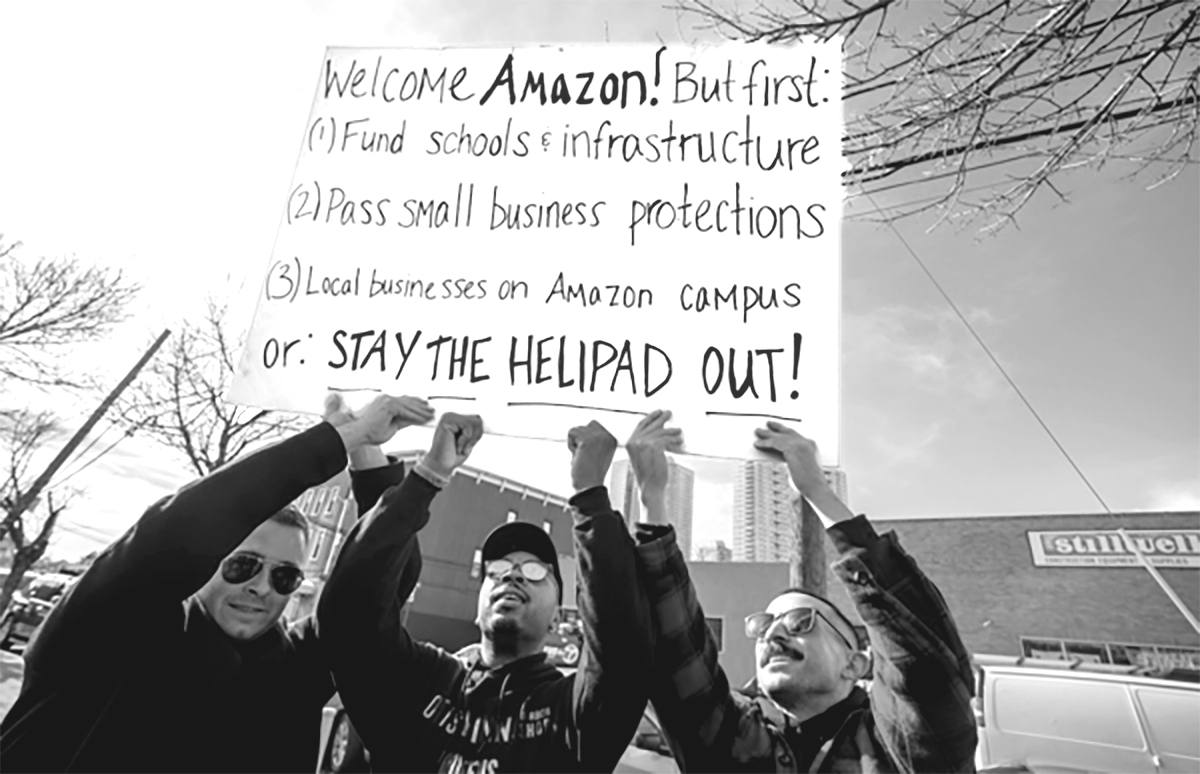

Was it Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s upset victory that galvanized grassroots organizing and pushed liberal representatives further to the left? Was it the unprecedented affordability crisis in New York City? Or was it Amazon’s unwillingness to consider labor union neutrality? Much like the unique constellation of tax incentives, perhaps the change of heart is proof of a historic singularity. The hypothetical damage this may cause for the city’s economic future is speculative at best. But the other benefits, those less explicitly economic-oriented, are already visible. Non-policy wonks are now versed in the discourse and practice of tax incentive policies and loopholes because conflict over the deal was so public and visible. Representatives of the City legislature have already proposed legislation to require more stringent public review of development projects, regardless of the project jurisdiction. Public opposition to hostile labor relations has been renewed, while conservative labor leaders who failed to hesitate before announcing support for Amazon have been exposed for compromising meaningful alliances with other unions or community advocates.

When I wrote the first version of this article, the pre-February 14th iteration, I presented an imagined alternative: what might public reaction have looked like if the Amazon negotiations had undergone public review? What concessions might have been won for the neighborhood, for the borough, for the city? Maybe more stringent local hiring requirements would have been implemented, a quota system requiring a percentage of employees from census blocks that actually fit the original criteria for “opportunity zones.” Perhaps the union presence would have been more meaningful, something beyond the construction phase of and building operations for the campus (32BJ SEIU negotiated an agreement with the project development team, who were contracted by Amazon). The official Memorandum of Understanding, the outlined agreement between New York and Amazon, makes no explicit reference to union labor. The possible outcomes are infinite. True, the public review processes in New York City are imperfect, often slow and inefficient. But New York City, on balance, has greater administrative transparency than other municipalities. Spending, public employee salaries, Council hearings, travel reports, and other bureaucratic ephemera are all publicly-available and reasonably accessible. The Economic Development Corporation (EDC), however, is mostly protected from this transparency.

As the primary economic development institution in New York City, the EDC, a quasi-public organization structured and operated like a private firm, focuses nearly all of its budget, manpower and planning on acting as the largest real estate broker in the city. Charged with managing all city-owned properties, the EDC leverages the sale or lease of its holdings to private investment to incur change–leaving the processes and outcomes of these transactions only broadly sketched; aspirational at best and intentionally disruptive at worst.

Assets in the EDC portfolio are diverse: the Brooklyn Army Terminal is an enormous riverfront industrial park that has been redeveloped as a state-of-the art manufacturing, retail, and commercial campus; the Essex Street Market (soon to be moved) is a historic city-owned marketplace in the Lower East Side that offers tenants subsidized rents; and the NYC Ferry system, the only transportation network under their jurisdiction. Operating costs for the EDC are met through asset revenues (i.e., rents collected from tenants), a surprisingly effective and efficient strategy. Capital  expenditures, however, are financed by the city or state, and managed by the EDC. It is in the design, execution, and outcome of these projects that the EDC’s divisive mandate comes into focus.

expenditures, however, are financed by the city or state, and managed by the EDC. It is in the design, execution, and outcome of these projects that the EDC’s divisive mandate comes into focus.

Under the de Blasio administration, the EDC has been tasked with negotiating between two broad and ambitious policy goals: Housing New York, which aims to construct or preserve 400,000 affordable homes over ten years; and 100,000 Good-Paying Jobs, an investment strategy to promote the growth of targeted industries in New York City and ensure future employment. Despite a reasonable assumption that these two objectives are ideologically aligned, the actual strategies and practices enacted to achieve them demonstrate dissonance, however unintended. This discrepancy, which magnifies the vicious cycle of property speculation, displacement, and uneven returns, is a consequence of the binary thinking that guides economic development: capital versus people, growth versus depth, and measurable outcomes versus lived experiences.

During the Bloomberg administration, more land was rezoned than during any other period in the city’s history. Much of this was in formerly industry-rich neighborhoods, like North Brooklyn and Willets Point; a significant swath of commercial land was rezoned in downtown Brooklyn to ease the transition to a commercial office district, a strategy that lacked the necessary regulations and restrictions to ensure that outcomes matched expectations. In the case of North Brooklyn’s industrial waterfront, manufacturers faced increasing real estate pressures, and many were forced to relocate or close. Thousands of manufacturing jobs were rendered obsolete by the land market in Brooklyn – jobs that offered living wages for workers who spoke little English, had only a high school degree, and were often recent immigrants. The high-impact real estate developments that usurped these neighborhoods can boast high levels of investment ratios and economic growth: metrics that eclipse their own origins and willfully pay obeisance to tax-rich residents and businesses. The EDC metabolizes these metrics, transforming them into a currency of legitimacy.

Despite managing such an enormous public resource (over 20 million square feet of real estate), the EDC has no popularly-elected leadership. Proposals are not subject to public votes (outside of rezonings that must pass the City Council), and the budget only recently reached the purview of elected officials’ oversight. The board, composed of 27 members, has roughly equal representation of private and public sector (local government and nonprofit) actors, but only one labor representative and only three education representatives. Based on the board’s background and interests, there is little extant capacity for human capital investment policies.

It’s almost as though the HQ2 deal has undergone a public review at this point, albeit an informal one. The city streets have become the shop floor, the postindustrial space of sociopolitical mobilization. In response to the last three months, New York City should consider a comprehensive review of not just tax incentive policies, but its affiliate agencies – the EDC in particular. The Amazon controversy has exposed the fault lines in governing ideologies and the pressing relevance of community organizing and labor solidarity. Although Amazon ultimately decided against New York City, it won’t be the last corporation to pursue the city’s generous business-friendly policies. This is an opportunity to capture momentum and pursue real changes, to reform the most powerful agency in the city into a representative body that reflects the wishes and needs of its constituents.