By Clay Matlin

As an artist, Timothy Belknap is very good when he lets his tinkerings speak for themselves, when he lets what is clearly a light and easy touch linger over complex ideas. And he is very good when he does not try to make beautiful things. Holland Cotter was right to highlight Belknap’s Dying Skeleton as the standout display at AIRPLANE for this past summer’s exhibition, Plein Air, held during Bushwick Open Studios. Belknap describes the piece as “a self contained and powered pneumatic aluminum skeleton that continuously mimicked breathing and movement until its battery expires. The robot is left in the local woods for a twenty-four hour period every season.” For Bushwick Open Studios, the skeleton was left in AIRPLANE’s back garden, alone amongst the flowers and grass. Its wheezings and buckings, its oddly human countenance, was far more amusing than upsetting. Yet there was also something deeper to this lonely automaton. The death throes, the loneliness, the bareness of the skeleton—it was mortality confronted with wry humor and irony.

Indeed, what made this work so moving and interesting, and what makes most of Button, Button a success, is that one never gets the sense of preciousness. Even when Belknap stumbles—as he does with his large button-on-fabric pieces in which buttons from his mother and grandmother’s collections are sewn onto fabric in a shape approximating the blood stains that sometimes mark the sidewalk in the Philadelphia neighborhood in which he lives—one cannot accuse him of being cute, perhaps a little crafty and a bit too aesthetically refined where an aesthetic concern is unwelcome. Belknap, though, has none of the mawkish precociousness that mars so much of Bushwick art these days with apparently endless artworks that seem to scream their very existence as objects to be adored. In fact, Belknap stands out because of what is an almost anti-aesthetic quality. Not that what he makes is visually unappealing. It isn’t. Take, for example, the “boom cakes” made of old fireworks, sitting on glass cake stands, which from a distance really do look like birthday cakes. But Belknap does not appear consumed with what is so often the downfall of artists, the overwhelming desire to make things beautiful. Here we might think of him as a disciple of John Chamberlain, who was not so interested in beauty as he was in the objectness of his sculptures, how they “fit” together to form a whole. When Belknap moves away from wholeness to the discrete interactions of parts and the urge to be pretty his art loses its strength.

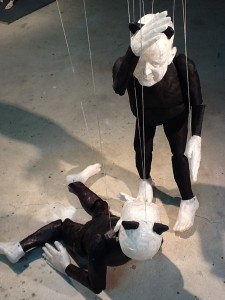

Even worse, the strange violence and aggression that courses through Belknap’s art is lost. When it lets itself out, however, and he chooses not to hide his weirdness, he is a deeply alluring artist. It is unfortunate that nothing in Button, Button quite touches the heights of Dying Skeleton, but Tender Hooligan comes closest. It is a pair of small skeletal legs and pelvis, almost of a child, attached to a machine that then move around. The legs go nowhere, their movements are fairly dull; but the sight of this skeletal lower half attached to a complex machine—whirring purple gears, black chains, numbers counting down until the legs start moving again—has that macabre touch that makes Belknap’s work so enticing. That we can see everything moving—each gear, hear each whirr, see the machine spool up with nothing hidden, see that it all “fits” together—makes Tender Hooligan a marvelous work. Its very objectness, the sheer clunkiness draws us in. The centerpiece of the exhibition Marionettes is, if not as strong as Tender Hooligan, an odd piece that is both a meditation on and an actual confrontation with violence. A reference to the recent beating death of an innocent man by members of the Philadelphia drug trade, Marionettes is made up of four automatons, men with the ears and bodies of pandas. They are connected, by wires and strings, to various switches and sensors around the gallery. These are then connected to red buttons of varying sizes that are dispersed throughout the exhibition in such a way that should one choose to press a button one of the three automatons will either kick or punch the fourth as he struggles to get up. The twist is that Belknap has positioned the buttons in such a way that when a button is pushed, depending on how or where we are standing, our view is obscured, leaving the implication of the action unknown. All we are left with, simply, is the knowledge that something did occur. This, like the title of the exhibition, is a direct reference to the 1985 Twilight Zone episode “Button, Button” in which a bored housewife receives a box with a button on it from a mysterious stranger, and is told that if she pushes the button she’ll receive $200,000. She is also told that when she pushes it, someone she does not know will die.

Marionettes is a headier work than Tender Hooligan, so its success was going to be harder to achieve and as such it is not as good. That Belknap provides the option for us not to see the consequences of our actions is quite brave, but the combination of the Twilight Zone and Philadelphia gang beat-downs does him no favors. It is without question smart and a bit sinister, but it should have been more. In some ways Button, Button is a bit maddening. There is at once too much going on—Belknap should have edited out some, if not all, of the button-on-fabric pieces. While conversely there are not enough of the objects that mark him as an artist rather than an aesthete. Belknap would do well to remember Ralph Waldo Emerson’s words on the place of the beautiful in art. Ever the religious man, Emerson reminds us that as “soon as beauty is sought not from religion and love, but for pleasure, it degrades the seeker . . . Beauty will not come at the call.” Beauty that gratifies our longings, that makes us partake in the pleasures of the sensible world is not an exemplary thing. Yet beauty will also not answer our call, it is not an animal to be trained. The beautiful is an ideal thing that finds expression in the world of appearances. It cannot be coaxed into existence, as Belknap is at times guilty of doing. One can make beautiful things, but one cannot set out to make beautiful things. The object either is beautiful or it is not. Emerson was of an idealist tradition with its line stretching all the way back to Plato, to the great Christian mystic Plotinus, to Kant, Schiller, to Hölderlin and Novalis, and over to America with Emerson. Timothy Belknap, when he is at his best, is an heir to that tradition. The idealists understood that the world is mysterious and perhaps terrible, but it is also beautiful; we seek to get at the ideal forms, to reunite with them, and thereby become one, as Plotinus tells us, with the great mystery again, to be unified.

That we can neither fully present the beautiful nor the ideal is less of a concern than the fact that beauty is there. It has an existence. Idealists, not surprisingly, believed in ideal forms, those things that lie outside the bounds of this world untouched by phenomena. The beautiful is one of those. It is an ideal. Emerson felt this to be true. Though he was an American variant of a European philosophical lineage, he shared their concerns, cared about unity, and he believed in the power of the beautiful. Art, he claimed, is there, even in the smallest of ways, to “throw a light upon the mystery of humanity.” When Belknap stays his hand and doesn’t think about beauty he lets us in on the mystery. However, when he seeks things that are better left unsought he produces objects that, while undeniably beautiful, are, if not degraded, then in some way sullied by his desires. Belknap’s automatons are beautiful in their construction and because of the generosity of feeling that courses through them. They have a unity and “fit” that his “beautiful” work does not come close to having. When he succeeds, he has made objects of beauty by the very fact the he did not try to make them beautiful. Belknap should stick to wholeness, the discrete charms of beauty are for him a trap of far too seductive power.

***

Timothy Belknap: Button, Button, at AIRPLANE Gallery, 70 Jefferson Street, Brooklyn, NY 11206. Up until October 21, 2012

Gallery hours: Sundays 12-6PM, and by appointment.