¶ 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0

BY METTE CHRISTIANSEN

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 The [postwar] artist became a person who must be an exceptional citizen who speaks a rare truth of sorts to the quiet breakdowns engendered by managed societies. Transgression was for the service of society as a whole – it pointed out hubris – and put the idea of society on trial.[1] (Liam Gillick)

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 The police is that which says that here, on this street, there’s nothing to see and so nothing to do but move along. It asserts that the space of circulating is nothing other than the space of circulation. Politics, in contrast, consists in transforming this space of ‘moving along,’ of circulation into a space for the appearance of a subject: the people, the workers, the citizens: It consists in re-figuring space, that is in what is to be done, to be seen and to be named in it. It is the instituting of a dispute over the distribution of the sensible.[2] (Jacques Rancière)

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 When the Situationist International (hereafter, SI or the Situationists) formed in Paris in 1957, they publicly proclaimed that their goal was to achieve a liberating change of society.[3] To the SI, life in the modern city – Paris in particular – had become increasingly emblematic of the experience of profound alienation that Marx had presented in Capital, and which the SI also saw as characteristic of modern bourgeois society.[4] To the SI, and their one-time friend and ally Henri Lefevbre, alienation had penetrated all domains of everyday life, including culture and society at large, and to the Situationists, the social effects of this alienation was both reflected in and perpetuated by mindless consumerism, the spectacle of mass media, and the urban built environment.[5] In the following, I will focus on the SI’s critical engagement with urban public space.[6] Through a unique form of spatial praxis,[7] the SI sought to reanimate life in the city, in ways that sought to overcome what they perceived as the hegemonic strictures of an overly rationalized and functionalist urban architecture.[8] By analyzing the situationist praxis in the context of how other critical theorists and philosophers conceives of the spatial dynamics of social and political life, I attempt to elucidate how and why public space – particularly its representation – is consequential both for how we can and do conceptualize, understand, act out, and experience urban public life and publicness, (counter)publics, and the public (whatever that means). Attending to questions about spatial production and construction, I suggest, also enables us to see that what we do in space is itself a production and a representation of space, and to consider how and to what extent space fixes the sensible and the doable. A focus on public space, then, can, I suggest, tell us something about the ontological and epistemological factors of our actions and social public life more generally, and perhaps it will yield a valuable insight into less theorized aspects of the nature and stakes of public assembly, public protest, and relational aesthetics[9] – matters that are addressed elsewhere in this collectively edited paper. Hopefully, this discussion can also be a valuable extension of a semester-long analysis and discussion of conceptions and formations of the public and publics, as they exist and come into being in and through public and private space.

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 Notions of Urban Public Space: The material as consequence and effect

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 The notion that physical public space has a significant effect on human social and political life was asserted repeatedly at a recent conference on public and publics.[10] In his keynote speech, geographer Don Mitchell claimed that physical public space is essential for political organizing and for the formation of publics. Protesters and social movements, he argued, need physical public space to exist and to sustain themselves, and, Mitchell suggested, without such space effective political struggle is impossible.[11] To Mitchell, then, physical public space is a space for social and political representation; it is a space where publics come together to struggle for social and political rights. But while physical public space is the site of struggle, it is also, to Mitchell, the stake of struggle, and this latter notion, I think, has profound implications for how the former plays out. But what does the assertion that space is a stake of struggle really mean, and what is implied by Mitchell’s claim that space is an ideal we must fight for?[12]

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 1 Turning to Jacques Rancière’s notion of the ‘distribution of the sensible’[13] both clarifies and complicates these questions in interesting ways. What Rancière is after in “The Distribution of the Sensible,” is to point out that human activity and everyday experiences are powerfully mediated by the social order, or what he calls the ‘police order’ – that is, by how the sensible is distributed in and through space, most often by dominant actors and institutions who control the means and relations of production in capitalist society, and who ensure the prescription and regulation of the existing arrangement of what is taken as legitimate and as truth:[14]

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0 The distribution of the sensible reveals who can have a share in what is common to the community based on what they do and on the time and space in which this activity is performed . . . it is a delimitation of spaces and times, of the visible and the invisible . . . that simultaneously determines the place and the stakes of politics as a form of experience. Politics revolves around what is seen and what can be said about it, around who has the ability to see and the talent to speak, around the properties of spaces and the possibilities of time.[15]

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 2 Thus, the social order to Rancière – and physical space is obviously a key part of how that order is expressed concretely – is an inherently political construction; with its segregation of the sensible into various regimes and its partitioning of people, physical space not only demarcates terms of inclusion and exclusion in communities and in society as a whole; it determines what can be thought, said, and done, and as such, the police order is bound up with the very concept of democracy. If the distribution of the sensible is decidedly non-random, if it is determined by those who control the means of production in a given social and historical context, and if an idea of democracy as contingent upon a certain sharing of the perceptible is accepted, it becomes clear how undemocratic the social order is for Rancière. Consequently, attempts at rebellion against an undemocratic distribution of the sensible will fail if they fall short of altering the distribution of the sensible itself. In other words, if the sensible is an expression of the ideology of those in power, those unaccounted for, who might be wholly excluded from the police order, can, to Rancière, only attempt to rebel by challenging the range of the sensible; only by reconfiguring it and representing it anew may their grievances become perceivable.[16] This, as we will see, is precisely what the SI tried to do; indeed, in what might be taken as their manifesto, the Situationists proclaimed such a transformation to be the aim of their revolutionary action within culture: more than merely expressing or explaining life, this action was to “enlarge life ‘ . . . [by] finding the first elements of a superior construction of the environment and new conditions of behavior.”[17] Interestingly, it is this form of opposition that, to Rancière, defines politics; although the social order is itself political and expresses a certain ideology and form of control, politics is all about dissensus and struggle against the police order. When the excluded challenge the social order, politics happens.[18]

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 1 Physical public space as stake on Rancière’s reading, then, can be understood in terms of the possibility for an active participation in a certain spatial configuration, or, as we will see below, in terms of what Henri Lefebvre calls ‘representations of space’ and ‘representational space.’ Following the Rancièrian logic, then, makes it clear why an expansive notion of the interconnectedness between the social, the spatial, and the political seems so crucial to a proper understanding of why what we do in space is both undercut and enabled by how space is structured and represented. It also allows us to cultivate a deeper appreciation for the fact that any public or publics who rely on physical public space for their representation, does so in a space that is always already structured by and representative of specific interests in material form. Rancière’s notion of the distribution of the sensible thus opens a way to think about how possible political publics may be formed through rule-based delimitations of space, and with its partitioning, the sensible itself.

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 Lefebvre’s philosophical notion of ‘social space’ and its three ‘moments’ – presented in The Production of Space as a spatial triad – both works as an explanatory framework for Rancière’s police order, and as an additional important dimension to an exploration of the nature of space and the ways in which the material and the social inhere in one another. Because Lefebvre’s spatial triad, or what he calls a ‘unitary theory’ of social space, pairs the philosopher’s space with the physical space where everyday life unfolds, his unitary theory also proves useful for a critical understanding of how space is itself produced and how it transforms.[19] What Lefebvre is concerned with in his conceptualization of space is “logico-epistemological space, the space of social practice, the space occupied by social phenomena, including products of the imagination such as projects and projections, symbols and utopias.”[20] In other words, Lefebvre is conceiving of real, physical space – the space produced and acted in by human beings. Social space is space as we live and experience it, and it is, in Lefebvre’s words, “a social product.”[21] But, as simple as the idea that humans create the world around them and that what they create in turn affects them might appear, spatial production is not as straightforward as might be expected, and this is reflected in Lefebvre’s three concepts – or what he calls ‘moments’ – of social space: ‘Spatial practice’ reveals itself through the physical, daily routines that make up urban reality. This reality, to Lefebvre, is defined by “the routes and networks which link up the places set aside for work, ‘private’ life, and leisure.”[22] In other words, this is the moment when the relations of production and reproduction make themselves especially felt, and where a certain perception of a partitioning of space imposes itself as a daily rhythm of sorts. This rhythm, Lefebvre posits, is supposed to be cohesive, but might not be logically coherent.[23] What is especially interesting here, is that urban reality and daily routines are seen as almost identical; if spatial practice is orchestrated around smooth transitions between “different” spheres of work, private life and leisure, spatial practice appears to both presuppose and promulgate society’s space, thus standing in a dialectical relation to such space. Lefebvre puts it like this: “The spatial practice of a society . . . produces [space] slowly and surely as it masters and appropriates it.”[24] The second moment is ‘representations of space’ – this is the conceptualized space of planners, scientists, and urbanists whose discourses on social space manifest themselves in physical forms like maps, plans, designs, and models. Lefebvre describes this space as the dominant space in any society, and it is easy to see why: representations of space are of necessity ideological; they trade in signs and abstractions which then can and does become concrete guidelines for human social action and interaction.[25] The third moment is ‘representational spaces,’ or lived space. This is the space of ‘inhabitants’ and ‘users’ – it is “the dominated – and hence passively experienced – space which the imagination seeks to change and appropriate. It overlays physical space, making symbolic use of its objects.”[26]

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 1 If lived space is a dominated zone, human action in space is rendered both contingent upon and productive of representations of space. The production of space, then, seems to create categories of users and representors of space, leaving little room for active dissent or resistance on behalf of the former against the latter’s spatial regimes of action and thought. With the spatial triad in hand, we can start to ask very direct questions about who and what gets a “place” in space. Lefebvre himself makes this pointed suggestion: “Perhaps . . . the producers of space have always acted in accordance with a representation, while the ‘users’ passively experienced whatever was imposed on them inasmuch as it was more or less inserted into, or justified by their representational space.”[27] If there are distinct users and producers of space, how are users manipulated and are those who manipulate free of being manipulated themselves? If architects and urban planners do have a representation of space, how did they obtain it and where? Whose interests are served in such representations? Whose stakes are even in the game? Space, clearly, is a site of ongoing social interactions and relations rather than mere results of them, and it is produced by dynamic interrelationships between the three moments of social space. So, perhaps the representors of space, themselves both products and producers of perceived and representational space, do not have absolute power of manipulation. And, it gets even more complicated: these three ‘moments’ of social space likely are not perceived as such – that is, even if they are known and recognized to some extent by users and producers, they may be disregarded or misconstrued, as Lefebvre suggests, and it is also entirely possible that these moments are at least partly unconscious.[28] This perhaps explains why the social mechanics of the mental and physical production of space seem to be so elusive.

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 1 But, if social space does not lend itself to easy interpretation, if it cannot be read without knowing how it is produced, how can we understand something like the now popularly recognized Lefebvrian “right to the city” as a “cry and a demand” for a renewed right to urban life;[29] that is, how can city dwellers hope to manage urban space for themselves in ways that supersede the control of both the state and capital, if they are not aware of the ways in which these forces work to make space? What Lefebvre means here, is that a right to the city entails more than a mere redistribution of access to existing resources. David Harvey’s notion, which is similar to Lefebvre’s, usefully describes what a right to the city necessarily entails: beyond a mere individual right of access to urban resources, it is instead more about a common right and freedom to change ourselves by transforming the city and this relies on a collective process of re-urbanization.[30] The urgency of claiming a right to the city for both Lefebvre and Harvey rests on the idea that the modern city, especially over the past century and a half, has increasingly become a sphere of encroaching alienation, and that an active takeover must be the foundation for a social and political disalienation. In The Production of Space, for example, Lefebvre argues that urban public space since the 19th century has become a material expression of the social alienation wrought by capitalism and its attendant modes and relations of production. Indeed, following SI co-founder Guy Debord, Lefebvre suggests that space has been entirely ‘colonized’ by capitalism.[31] As a consequence, to Lefebvre, urban public space is a highly contested place where the interests of the wealthy and the powerful are disproportionately represented. Space, Lefebvre argues, is planned, built and rebuilt according to certain bourgeois ideals of inclusion and exclusion of specific publics, and due to competing interests and hierarchical power relations, urban public space, although presenting itself as neutral and as depoliticized, is anything but.[32] We can look at Baron Haussmann’s spatial reconfiguration of Paris as a concrete example of this. Due to Haussmann’s urbanization of Paris, a wholesale destruction of working class neighborhoods resulted in the material erasure of the powerless proletariat from the center of the city. This undesired public was assigned to the periphery and kept under military surveillance. The forced relocation of one type of public in the service of another is no longer legible in central Paris, and that, precisely, is the point: space makes and erases public memory; it renders intelligible only certain parts of the past and present, and thereby affects how publics understand and interacts in and with space.

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 We can draw a couple of important ideas from the above, which also resonates with what has been suggested in Rancière and in Mitchell: Clearly, space is produced and it is a political matter; capitalism’s hegemonic element has a huge claim on how space is organized and space can therefore be seen as a condition of the operation of capitalist forces, because space becomes a place where the relations of production are reproduced, making space an instrument for a form of planning pertaining to a capitalist logic of growth. But, despite alienation and despite capitalism’s disproportionate control over the production of space, the demand for a right to the city keeps making itself heard. The city, although a place of alienation and domination, is, to both Lefebvre and Harvey, also imbued with opportunities for creating alternative forms of urban life.[33] If we view the city as a place made up of different layers of spaces which are manifested through collective social practice, instead of as a place merely pieced together by different patches of space, an opportunity arises for emancipatory imbrication of space upon space.

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0

¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0 Situationists to the rescue: social disalienation on spatial terms

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 The Situationists came together in 1957 through the unification of the postwar avant-garde art movements Lettrist International – a Paris-based group of avant-garde artists and political theorists – and the International Movement for an Imaginist Bauhaus, an anti-functionalist group of artists led by the Danish painter Asger Jorn.[34] Through the construction of ‘situations’ and spatial tactics like détournement and dérive, the Situationists took up the battle within and against an urban space they saw as the material expression of human social alienation.[35] The fundamental aim of this group of artists and intellectuals was a revolutionary positive transformation and emancipation of modern urban life, particularly as it played out in Paris in the years following the Second World War. Guy Debord captured this aspiration in stark terms in the “Report on the Construction of Situations and on the International Situationist Tendency’s Conditions of Organization and Action”: “FIRST OF ALL, we think the world must be changed. We want the most liberating change of the society and life in which we find ourselves confined. We know that such a change is possible through appropriate actions.”[36] To this end, they drew much inspiration from Lefebvre’s work on the critique of everyday life,[37] as illustrated both in their praxis and their theoretical work which was published in their collectively edited journal Internationale situationniste.[38]

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0 Overall, there are many links and similarities between the work of Lefebvre and the Situationists, including their analyses of modern society as ‘spectacular’, as wholly commodity and consumer-oriented – what Lefebvre elsewhere has called the bureaucratic society of controlled consumption – and as fraught with human alienation.[39] Like Lefebvre, the Situationists saw everyday life in the metropolis as the site of critique and revolutionary social change, and like Lefebvre, they perceived those tasks through a Marxist framework. The Situationists’ approach is prominently articulated in Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle.[40] In this philosophical work of Marxist critical theory, which was an important guideline for situationist theory and praxis, Debord raises an aggressive critique of consumerism, commodification, and a culture wholly perforated by spectacular objects. In 221 unambiguous theses, Debord describes his contemporary urban and societal context as shattered by “an immense accumulation of spectacles.”[41] Debord conceives of ‘the spectacle’ as a confluence of capital and culture, whereby the social relations among people are mediated by images which are falsely perceived as having a socially unifying effect.[42] For Debord, the spectacle is distributed throughout the built urban environment, and therefore has detrimental effects on both the individual human psyche and urban social life more generally.[43]

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 1 The Situationists were keenly aware of the difficulty of meaningful collective resistance against a society so completely perforated by spectacular images, but instead of only sticking to a theoretical critique of modern architecture and the Parisian urban grid – like they had done at the outset of their collaboration – the Situationists started critically interrogating and intervening in the streets of Haussmann’s Paris in the late 1950s.[44] Their explicit aim was to create a space for alternative social relations, and their spatial tactics sought to undermine Paris’ monumental authority through practical interventions and ‘incorrect’ uses of preordained public space.[45] What is at stake, then, for an aesthetic spatial practice that seeks to enable new modes of sense perception in an urban environment, and with it, new forms of political subjectivity? Ranciére again: “Artistic practices are ‘ways of doing and making’ that intervene in the general distribution of ways of doing and making as well as in the relationships they maintain to modes of being and forms of visibility.”[46] This suggests that a form of positive interruption (“doing and making”) is necessary to constitute a truly activist stance with revolutionary potential to alter, at the very least, the sensation of the distributed if not the distributed itself.

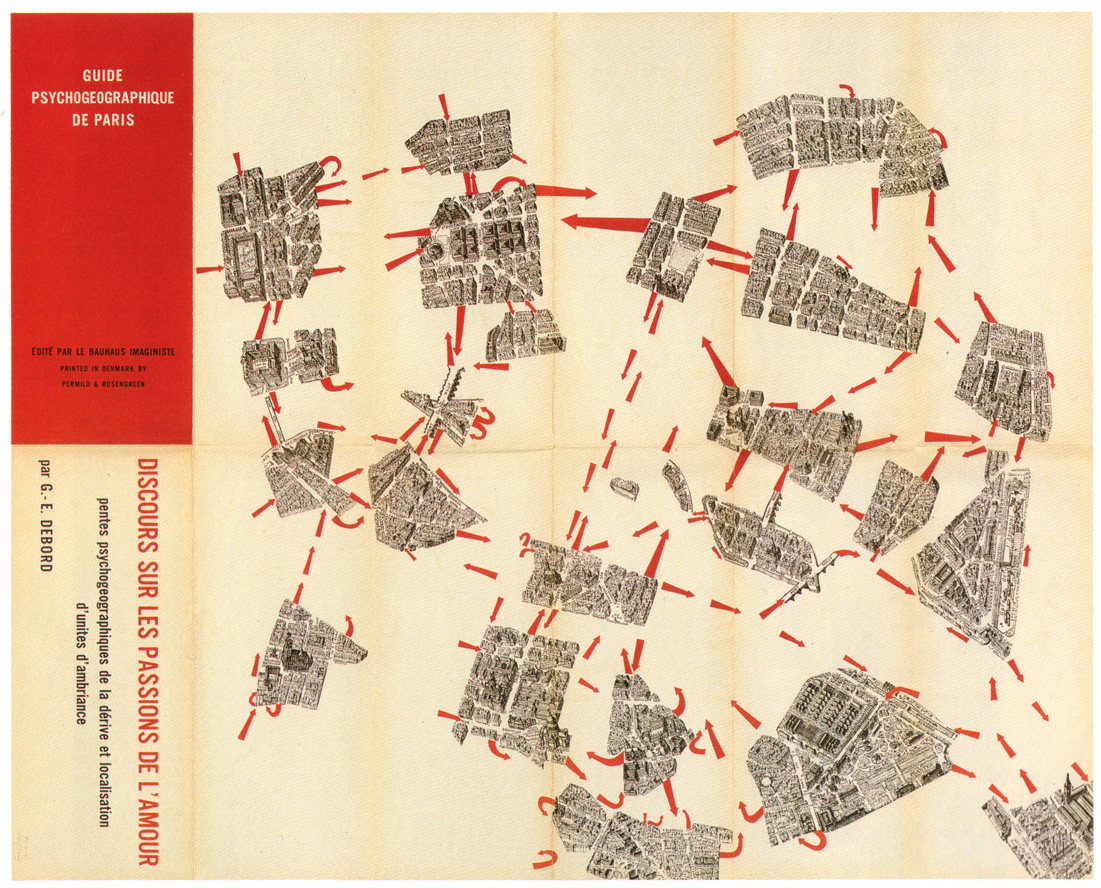

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 At the core of the SI’s tactics was the construction of ‘situations’ through which the artists sought to implement concretely what Debord defined as ‘psychogeography’ – an urban ideology of sorts that the Situationists were deeply committed to.[47] Debord defined psychogeography as “the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals.”[48] A psychogeographic relation to urban space is one that for the Situationists understands urban space as constituted by and constitutive of the drama of self-consciousness and mutual recognition; as a space for possible recognition of the self and the ‘other,’ and as a space for possible social collectivity.[49] This psychogeographic map, published in 1957, captures the underlying philosophy of the notion and shows what it looks like put into action:[50]

¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0

¶ 24

Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0

¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0

¶ 26 Leave a comment on paragraph 26 1 The map shows the Situationists’ thinking about the mental re-construction of urban space according to a psychogeographic proviso. It subverts the image of a map by destroying the omnipresent view from ‘nowhere,’ and instead it emphasizes spatial movement (the directional red arrows) in and around certain psychological hubs that the drifter would move through based on attraction to spaces and momentary atmospheric ambiances, and not the dictates of the infrastructural grid. In this way, psychogeography plays out in the streets as “experimentation by means of concrete interventions in urbanism.”[51] This action on the environment is captured by the concept of ‘unitary urbanism,’ which the SI defined as a method by which “arts and techniques of all kinds should be put to use in a way that would contribute to the composition of a unified milieu.”[52] Only through a collectivized effort – conceived as a form of integral art – at the level of urbanism, would it be possible to subvert already established forms of architecture and urbanism.[53]

¶ 27 Leave a comment on paragraph 27 2 One of the daily tactics that the SI employed to overcome the socially atomizing effects of the urban environment was the dérive. Constituted through unplanned and uncoordinated movement through urban space, the dérive was essentially an experiemtnal game directed at a search for encounters with otherness.[54] This search could be instantiated at any given moment – in fact, part of the point was to interrupt oneself in one’s habitual or need-based movement through space and instead of attending to work or predetermined leisure activities, one would give in to and be drawn by the urban attractions that happened along the way from one point to another.[55] The Situationists would undertake such adventurous wanderings through urban space by exploring areas of Paris that differed by class, race, and ethnicity.[56] In this way, they practiced a kind of psychic reconfiguration of the modern urban grid, and through an external illogical or oneiric state where movement through space is based not on need but desire, the Situationists managed to recuperate urban public space by contravening what they saw as its fundamentally alienating nature. Similarly, détournement was a tactical response to an environment and to forms of culture that is not of one’s own making; a way to engage forms that alienate and predetermine. Engaging in détournement is an effort to create situations that turn capitalist elements of both physical and literary space against themselves by acting in and on such spaces in ways that go against their alienating grain.[57] The situationists used détournement – a technique originally invented by Debord’s old group, the Lettrist International – as a way to appropriate aesthetic forms towards what two of the Situationists called “a subversive rewriting of the capitalist ideological illusion in the name of de-alienation.”[58] This rewriting, conceived of as a “cultural weapon” and as a means of “proletarian artistic education” can take many forms and it was not exclusively directed at the built environment – in fact, anything can be diverted, including poetry, film, clothing, painting, and posters.[59] What the practice of détournement boils down to, then, is a twisting of words, phrases, fictional characters, and all manner of modes of aesthetic expression, in ways that undermine their intended, planned, and ideologically predetermined realization. The SI suggested that in the architectural realm, and in the sphere of everyday social life, such interventions can consist in changing the street names or titles of buildings – thus giving them a new sense or meaning – or rearranging or putting to unconventional uses familiar gestures, habits, and everyday objects. For example, clothing, which has significant emotional connotations, can be used in the service of disguise or play, creating alternative evocative expressions of unexpected or controversial identities. Taken together, a number of deliberately changed determinant conditions will allow groups of people to détourne entire situations towards desired ends.[60] In other words, détournement was conceived as a tactic of the powerless, as a “destruction of present-day conditioning,”[61] and as a decisive turn of pre-existing commercial forms towards revolutionary ends. This theoretical sketch of the Situationists’ practices shows that what they did was to fight space on its own terms – they intervened in it by moving through space against its own script and intention, thus negating its commanding laws of gravity and proposing an alternative spatial sensation, a new range of the sensible, in Rancière’s term. The aesthetic, spatial praxis of the Situationists, then, aimed at shaping the idea of what a city is and can be, what it can and should feel like, architecturally, socially, and spatially, and in that way, their praxis has echoes of a Lefebvrian right to the city.[62]

¶ 28 Leave a comment on paragraph 28 0

¶ 29 Leave a comment on paragraph 29 0 The Limits of Artistic Situations in Public?

¶ 30 Leave a comment on paragraph 30 1 In “Art and Democracy: Art as an Agonistic Intervention in Public Space,” Chantal Mouffe contends that artistic practices can widen conceptions of public space through counter-hegemonic interventions in a host of different social and political spaces, thereby constituting an effective opposition to the totalizing structuration of culture and of social, public spaces by capital.[63] I suggest that the Situationists did exactly that – they intervened in urban public space which, as we have seen, is anything but culturally and politically neutral. We saw, with Rancière, that the way in which we can experience daily life in urban space, has everything to do with (non)democratic principles of distributions of the sensible. The sensible is, of course, not just relevant to the experience of urban public space, but important to how we conceive of being public in an environment that is configured according to a capitalist police order, which essentially determines what is seen, heard, said, and thought. The SI did not make urban space more democratic, per se, but by disobeying the alienating architectural infrastructure of the city, they effectively imposed on urban space new ways of construing the sensible through tactics that created spaces of collectivity and sociality. Mouffe cites Brian Holmes to suggest exactly this point: Art – and since Mouffe does not specify what she means by the term ‘art’ I think the spatial praxis of the SI falls under this category – can create a space for “collective reflection on the imaginary figures [capital] depends on for its very consistency, its self-understanding.”[64] Mouffe also contends that any social order is contingent and unstable; that it continuously goes through cycles of change during which it is constituted, upended, and reconstituted, and this, I think, is a useful reminder of the fact that social experience is not a predetermined, static affair whereby a predestination kicks us into a place from which we can only comply. This, at least, seems to be the point in both Rancière, Lefebvre, and the SI. The SI fought space on its own terms – they intervened in the hegemonic representation by stealing away time and space from the dominant police order to overlay it with alternative sensations. One of the reasons why such creative interventions works, I think, is that urban public space is volatile – it is a space where different power differentials intersect, are constituted, affirmed, challenged, reasserted and overturned – no one is in complete control of public space which is what makes it volatile. A focus on physical public space allows us to think about power in concrete terms. We know, or can easily find out, who funded, planned, designed, and constructed buildings, parks, streets, and plazas, and that makes it possible to discover which social, political, and economic actors and interests are vested in and represented by specific uses of space. This knowledge, then, opens the door for a critical engagement and makes a fight for or against space immensely possible.[65]

¶ 31 Leave a comment on paragraph 31 1 It could be argued that the significance of space is overstated here – that asserting that space plays such a prominent role in cultural and social relations, is placing an undue emphasis on its relevance for public life. Some might argue that space cannot be a driver of social and political change, and that likewise, artistic, spatial practices like the one reviewed here, fall short of producing any substantial difference in human relations. But, I think it is equally valid to suggest, with Mouffe, that strictly calculated and segregated public spaces lead to a lack of the kinds of conditions that Mouffe sees as inherent to what she calls radical democracy. To her, democracy is by nature agonistic, it is about real challenges, irritation, confrontation and dissensus: “To revitalize democracy in our post-political societies, what is urgently needed is to foster the multiplication of agonistic public spaces where everything that the dominant consensus tends to obscure and obliterate can be brought to light and challenged.”[66] It is clear that art has a political role to play in a Mouffian radical democracy; the SI, like other artists, are good at expressing their opinions, beliefs, and ideas, and they projected unexpected ‘images’ into urban space, drawing attention from a diverse public to the kinds of problems perceived as especially detrimental to a flourishing urban life and a sense of collectivity, solidarity, and togetherness.

¶ 32 Leave a comment on paragraph 32 0 Footnotes

¶ 33 Leave a comment on paragraph 33 0 [1] Liam Gillick, Industry and Intelligence (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016), 45.

¶ 34 Leave a comment on paragraph 34 0 [2] Jacques Rancière, “Ten Theses of Politics,” in Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics, trans. Steven Corcoran (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), 45.

¶ 35 Leave a comment on paragraph 35 0 [3] See Debord, “Report on the Construction of Situations and on the International Situationist Tendency’s Conditions of Organization and Action” in the Situationist Online Archive: http://www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/si/report.html

¶ 36 Leave a comment on paragraph 36 0 [4] Ibid. For a quick overview of Marx’s notion of alienation, see for example the online Encyclopedia of Marxism: glossary of terms, https://www.marxists.org/glossary/terms/a/l.htm. Alienation in Marx is a multifaceted notion tied to commodity production and wage labor, the prevalent forms of production and labor in modern bourgeois society. Alienation, to Marx, rests in the concept of reification, whereby human social relations are conceived as relations between things. To overcome alienation, argues Marx, the labor process must change such that human relationships with the labor process can be restored.

¶ 37 Leave a comment on paragraph 37 0 [5] See Tom McDonough, The Situationists and the City (New York: Verso, 2009), 3-12.

¶ 38 Leave a comment on paragraph 38 0 [6] Throughout, unless otherwise noted, urban public space denotes physical space.

¶ 39 Leave a comment on paragraph 39 0 [7] Praxis is here understood as, simply, action based on and informed by reflection and committed to a search for truth and human well-being.

¶ 40 Leave a comment on paragraph 40 0 [8] McDonough, The Situationists and the City, 3-12.

¶ 41 Leave a comment on paragraph 41 0 [9] See Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics (Dijon: Les Presses du Reel, 1998), 113. Art critic and historian Nicolas Bourriaud coined the term ‘relational aesthetics’ in this 1998 book of the same name, and defined it as: “A set of artistic practices which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and the social context, rather than an independent and private space.”

¶ 42 Leave a comment on paragraph 42 0 [10] “Public and Publics” conference, March 30, 2017, CUNY Graduate Center. For full program and speaker bios see: http://www.centerforthehumanities.org/programming/the-public-and-publics-conference

¶ 43 Leave a comment on paragraph 43 0 [11] Don Mitchell, keynote speech at “Public and Publics” conference – see note 3.

¶ 44 Leave a comment on paragraph 44 0 [12] Ibid.

¶ 45 Leave a comment on paragraph 45 0 [13] In this context, the sensible simply refers to what is apprehended by the senses.

¶ 46 Leave a comment on paragraph 46 0 [14] Jacques Rancière, “The Distribution of the Sensible,” in The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible, trans. Gabriel Rockhill (New York: Continuum, 2004.)

¶ 47 Leave a comment on paragraph 47 0 [15] Ibid., 12-13.

¶ 48 Leave a comment on paragraph 48 0 [16] Ibid., 14.

¶ 49 Leave a comment on paragraph 49 0 [17] See Guy Debord, “Report on the Construction of Situations and on the International Situationist Tendency’s Conditions of Organization and Action,” written 1957, trans. Ken Knabb, http://www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/si/report.html. This link gives access to a rich archive of pre-situationist, situationist, and post-situationist writings.

¶ 50 Leave a comment on paragraph 50 0 [18] Ibid., 14-16

¶ 51 Leave a comment on paragraph 51 0 [19] See Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 1991).

¶ 52 Leave a comment on paragraph 52 0 [20] Ibid., 11-12.

¶ 53 Leave a comment on paragraph 53 0 [21] Ibid., 26.

¶ 54 Leave a comment on paragraph 54 0 [22] Ibid., 38.

¶ 55 Leave a comment on paragraph 55 0 [23] Ibid.

¶ 56 Leave a comment on paragraph 56 0 [24] Ibid.

¶ 57 Leave a comment on paragraph 57 0 [25] Ibid., 38-39.

¶ 58 Leave a comment on paragraph 58 0 [26] Ibid., 39.

¶ 59 Leave a comment on paragraph 59 0 [27] Ibid., 44.

¶ 60 Leave a comment on paragraph 60 0 [28] Ibid., 72-73.

¶ 61 Leave a comment on paragraph 61 0 [29] See Henri Lefebvre, “The Right to the City” in Writings on Cities, trans. Eleonore Kofman and Elizabeth Lebas (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 1996), 158.

¶ 62 Leave a comment on paragraph 62 0 [30] See David Harvey, “The Right to the City,” New Left Review 53, (2008), 23-40.

¶ 63 Leave a comment on paragraph 63 0 [31] Lefebvre, The Production of Space, 365; Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, trans. Ken Knabb (Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2014), 4-5.

¶ 64 Leave a comment on paragraph 64 0 [32] Lefebvre, The Production of Space, 10-11.

¶ 65 Leave a comment on paragraph 65 1 [33] See Harvey, “The right to the City,” 39-40. Harvey argues that many groups focusing on urban dispossession have emerged, albeit not in the coherent, global-reach fashion required for a successful transformation of the collective right to the city. Harvey recognizes how difficult it is to organize and to truly collectivize such struggles for the urban, but at the same time sees it as immensely possible. He suggests that as part of unifying the struggle, ‘the right to the city’ should be adopted as a working slogan and a political ideal “precisely because it focuses on the question of who commands the necessary connection between urbanization and surplus production and use.” Harvey, 40.

¶ 66 Leave a comment on paragraph 66 0 [34] Asger Jorn was one of the founding members of CoBrA (1948-51) – a group of painters whose founders came from cities (Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam) that were under Nazi occupation during WWII. CoBrA painting is best known for a spontaneous and rebellious style of painting which was inspired by the so-called ‘uncivilized’ art made by children and the mentally ill. The group’s political stance was against what they saw as the too conservative, sterile, rational, and dictatorial approaches of contemporary practices like Social Realism, abstraction and naturalism.

¶ 67 Leave a comment on paragraph 67 0 [35] See McDonough, The Situationists and the City (London and New York: Verso, 2009).

¶ 68 Leave a comment on paragraph 68 0 [36] Debord, “Report on the Construction of Situations and on the International Situationist Tendency’s Conditions of Organization and Action.” See online link in note 17.

¶ 69 Leave a comment on paragraph 69 0 [37] See Henri Lefebvre, Critique of Everyday Life, trans. John Moore (one-volume edition) (London and New York: Verso, 2014). The first volume of this three-volume work came out in 1947, and it is this volume that focuses most intensely on alienation; an alienation Lefebvre sees as extending beyond the sphere of production and into the private, social and cultural spheres outside of the workplace. Lefebvre, Critique of Everyday Life, 168.

¶ 70 Leave a comment on paragraph 70 0 [38] The Internationale situationniste came out in 12 issues, with the first publication in 1958 and the final in 1969. The material is politically radical and the powerful prose is a definite indication of the Situationists’ strong commitment to their cause of a revolutionary upending of the spectacular modern society, which to them is characterized by a deep-seated alienation by and through consumption. All issues are available through this hyperlink: http://www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/si/situ.html

¶ 71 Leave a comment on paragraph 71 0 [39] For an insight into the relationship between Lefebvre, Debord, and the Situationists see Kristin Ross’ interview with Lefebvre in Guy Debord and The Situationist International: Texts and Documents, ed. Tom McDonough (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2002), 267-85.

¶ 72 Leave a comment on paragraph 72 0 [40] See the New York Times op-ed from February 2, 2017, for an interesting analysis of the continued relevance and applicability of The Society of the Spectacle in the age of Trump. https://nyti.ms/2lm3c9E.

¶ 73 Leave a comment on paragraph 73 0 [41] Debord, Society of the Spectacle, 2.

¶ 74 Leave a comment on paragraph 74 0 [42] Ibid. Spectacular society, to Debord, is one where images deceive both their spectators and creators who are led to believe that the unreal is, in fact, the real: “The spectacle presents itself simultaneously as society itself, as a part of society, and as a means of unification. As . . . the focal point of all vision and all consciousness. But due to the very fact that this sector is separate, it is in reality the domain of delusion and false consciousness: the unification it achieves is nothing but an official language of universal separation.” 2.

¶ 75 Leave a comment on paragraph 75 0 [43] Ibid.

¶ 76 Leave a comment on paragraph 76 0 [44] See McDonough, The Situationists and the City, 10-12.

¶ 77 Leave a comment on paragraph 77 0 [45] See Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. Steven Rendall (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), xix. Certeau makes an instructive distinction between the tactical and strategic. He conceives of the tactical as a form of trespassing, an intervention which can disrupt circuits of power, and as such, the tactical is an operation from ‘the outside’ which the ‘other’ uses to critique the dominant order. In contradistinction, the strategic is possible when one holds power and controls the uses of, for example, space or any resource which may be valuable to a given public.

¶ 78 Leave a comment on paragraph 78 0 [46] Rancière, “The Distribution of the Sensible,” 13.

¶ 79 Leave a comment on paragraph 79 0 [47] See McDonough, The Situationists and the City, 10-12, 59-65.

¶ 80 Leave a comment on paragraph 80 0 [48] Debord, “Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography,” in Les Lèvres Nues #6, 1955; “Report on the Construction of Situations and on the International Situationist Tendency’s Conditions of Organization and Action.”

¶ 81 Leave a comment on paragraph 81 0 [49] Debord, “Report on the Construction of Situations and on the International Situationist Tendency’s Conditions of Organization and Action.”

¶ 82 Leave a comment on paragraph 82 0 [50] Taken from the SI online archive: http://www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/presitu/geography.html

¶ 83 Leave a comment on paragraph 83 0 [51] Debord, “Report on the Construction of Situations and on the International Situationist Tendency’s Conditions of Organization and Action.”

¶ 84 Leave a comment on paragraph 84 0 [52] Ibid.

¶ 85 Leave a comment on paragraph 85 0 [53] Ibid.

¶ 86 Leave a comment on paragraph 86 0 [54] See Gilles Ivain (Pseudo. Ivan Chtcheglov), “Formulary for a New Urbanism” in McDonough, The Situationists and the City, 32-67. SI member Ivain had studied psychogeography starting in 1953, and in this piece, which was first published in the 1958 issue of Internationale situationniste, Ivain addresses the role of architecture as a means of expressing and affecting spatio-temporal experience, and he calls for the importance of built environment that could be modified in accordance with the desires of its inhabitants.

¶ 87 Leave a comment on paragraph 87 0 [55] It is tempting to impose Baudelaire’s flâneur on the situationist dérive, but Baudelaire’s wanderer is of a different social and economic class than the artist composing the Situationist International, and Debord and his fellow Situationists would likely see such a comparison as completely misplaced and misunderstood.

¶ 88 Leave a comment on paragraph 88 0 [56] McDonough, The Situationists and the City, 11-12.

¶ 89 Leave a comment on paragraph 89 0 [57] Ivain, “Formulary for a New Urbanism” in McDonough, The Situationists and the City, 146.

¶ 90 Leave a comment on paragraph 90 0 [58] Ibid., 146.

¶ 91 Leave a comment on paragraph 91 0 [59] See Debord and Wolman, “A User’s Guide to Détournement,” trans. Ken Knabb, available through this link: http://www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/presitu/usersguide.html

¶ 92 Leave a comment on paragraph 92 0 [60] Ibid.

¶ 93 Leave a comment on paragraph 93 0 [61] Ivain, “Formulary for a New Urbanism” in McDonough, The Situationists and the City, 149.

¶ 94 Leave a comment on paragraph 94 0 [62] See Henri Lefebvre, “The Right to the City” in Writings on Cities, ed. Eleonore Kofman and Elizabeth Lebas (Cambridge, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 1996). In “The Right to the City,” Lefebvre argues for a complete renegotiation of the social, political and economic relations of capitalism, and a set of tactics would likely have been insufficient for the kind of radical restructuring he had in mind. One of the central demands Lefebvre puts forth is that a decentralized production of space must replace the state as the realm of decision-making. The Situationists can be seen as doing precisely that – producing space anew – through their daily social practices, thereby reclaiming a decision-making power.

¶ 95 Leave a comment on paragraph 95 0 [63] Chantal Mouffe, Art and Democracy: Art as an Agonistic Intervention in Public Space,” Art as a Public Issue (January 2007): 1–7. http://www.onlineopen.org/art-and- democracy.

¶ 96 Leave a comment on paragraph 96 0 [64] Ibid., 2.

¶ 97 Leave a comment on paragraph 97 0 [65] See Nato Thompson, Seeing Power: Art and Activism in the 21st Century (Brooklyn, NY: Melville House, 2015). Thompson suggests that art which self-consciously acts at the intersection of art and politics has the ability to shine a light on the significance of physical space as a site and stake of resistance.

¶ 98 Leave a comment on paragraph 98 0 [66] Chantal Mouffe, On the Political: Thinking in Action, (London and NY, Routledge, 2011), 20.

Connecting the idea of the “distribution of the sensible” to Tyler’s case study, what is the distribution of the sensible in the rural vs. in the urban? What do we lose, sensibly speaking, if we give in to the increasingly irresistible pull of the city? If we lose touch with a particular (rural) distribution of sensibility for a generation, what else might we lose?