The surrealist poet, Carlos de Rokha was born in 1920 in the city of Valparaíso, Chile, the oldest son of poets Winett and Pablo de Rokha. There is some discrepancy about the exact date of his birth, however: a Wikipedia page dates his birth as August 17, while other sources have Santiago as the city, and not Valparaíso. The first well-researched edition of his work, El orden visible, Vol. II (2011), documents the date as March 28. Still, a microfilm image of the Chilean Registry of Births, lists the date as July 28. Similarly, there are discrepancies about the dates of publication when some of his poems first saw the light of day, all of which adds to the elusive quality of the biography of this unconventional and talented writer.

Update: CLAGS awarded the 2019 Monette-Horwitz prize for my doctoral dissertation, “Una enunciación intersticial: la poética del destierro de Carlos de Rokha,” a study of queer poetics and suicide in the Chilean Vanguard Era. My research interests include issues of race, class, and gender in Latin American and Latinx literature in Spanish and English, surrealism, and queer poetics.

Although it seems as though we know a great deal about the de Rokha family, the writers, the painters, and the great contribution of his father, Pablo de Rokha*, to the literary vanguards of early 20th century in the Southern Cone, there is a great deal more to be said. It is only recently, for instance, that critical studies have been undertaken in earnest, and more complete editions of the work of the elder de Rokha have become available. Regarding the poetry of Winett de Rokha, on the other hand, it is a complicated work that includes early feminist, indigenista, marxist, populist, anti-fascist, vanguard poetry (even a strange, early poem to Stalin), and has yet to be rediscovered.

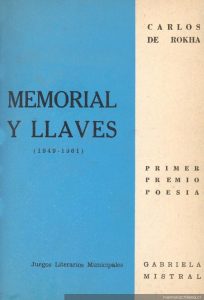

For now, back to our poet. Had he lived beyond the early hours of September 29, 1962 he would have been 98 years old, a not inconceivable age to be alive these days. But Carlos de Rokha lived quite a difficult life, struggling with mental illness at a time when not enough was known about schizophrenia and depression, and in addition to the social stigma it carried, there was little hope of treatment. On the dawn of that Spring day in Santiago, it is possible that Carlos met his death due to an accidental overdose of medications and alcohol, or perhaps he went knowingly, as he often wrote, in the hundreds of poems that were left behind. Only two books were published during his lifetime, Canto profético al primer mundo (1944), and El orden visible, volume I (1956). Two more poetry collections were released posthumously, Memorial y llaves in 1964, and Pavana del gallo y el arlequín, in 1967; but in a tattered suitcase he left manuscripts and detailed plans for two other volumes comprising the work of nearly two decades. The first of these, El orden visible, volume II, was finally published in 2011, and there are plans to publish the last volume in the coming years.

The work of Carlos de Rokha is the subject of my doctoral dissertation, and I am also at work on a translation into English of selected poems that represent the various stages of his lyric. Although he was a poet whose work was hardly known outside a small circle, and little critical work had been done until the beginning of this century, he was regarded by many who read him to be a gifted poet who pledged to live his life as the embodiment of poetry; autodidactic and eccentric, a kind, generous friend, almost childlike in his demeanor, of fluid gender, at times succumbing to fantastic visions, he was one of the most interesting figures of the Chilean literary tradition. His early work of unmistakeable and fecund imagery was shaped by the literary currents of the vanguards, particularly by the late surrealism of Latin America in the late 30s, but he searched beyond the dazzling images to a metaphysical, even cosmic, lyrical essence. Doubtless, his work is extremely difficult to translate, yet impossible to put aside. This post may experience many revisions before this first bilingual edition comes out.

Often remembered as one of the poetas malditos of the generación del ’38, in Chile, de Rokha was indeed a friend and comrade of the members of the surrealist group, la Mandrágora, and considered to be one of the younger poets of that generation. However, the greater part of his work was completed in the next two decades, and, with the publication of the second volume of El orden visible, we now know that this was a poet who reached his maturity in the late 1950s. From this point to his death in September of 1962, his work experienced a transition to greater lyrical refinement within a more somber, interior landscape. A blend of all these elements can be appreciated in the poems below (my translations in progress), which date from the later period of his work, found in the posthumous collections.

(*all materials with permission of the Fundación de Rokha, Santiago, Chile) For further information on Carlos de Rokha and the writers of the Vanguardia Chilena, see the Digital Library memoriachilena.cl

~Mariana Romo-Carmona, PhD

Litany

I shall die, garlands of skies

Who will hold me

Will it be the cup where I return

my life to the great sea of origins?

I shall fall, garlands of water

If you come, my song will rise

to a chorus of angels,

if you come, I will be the joyous confines

blinding in pure echoes.

Oh, echo of limits, sustain me!

Choirs of angels, watch over me!

at the height of the night of lamps.

I know not whether I am an ancient tremor in my clepsydra

or a space in the wind among the ferns.

I shall return, doves of the glass.

I shall depart, violins in the sea spray

diamond roosters, seagulls of the rain.

© translation by M. Romo-Carmona, 2018. “Letanía,” Memorial y llaves, p. 23

Ode

Oh, sea, oh darkened time of my blood!

I stand naked before your corolla

of impatient breezes. Oh, time!

sustained by your blue columns

sky of the seas, give me back

the stem of anguish, the dove

of air, her silence

©translation by M. Romo-Carmona, 2018. “Oda”, Memorial y llaves, p. 33

Religion (Memorial y llaves, p. 65)

Distant like a god who just

created the world

everything rushed toward me. The beasts and the flowers

the savage wine burned my desire

and then you named that silence

But I did not know

what windy solitude bloomed between your fingers.

I did not know

that my cruelty was the same as your love

and that death

grows like a scream in the cities

But the last doves have not yet been slaughtered

Wait for me.

©translation by M. Romo-Carmona, 2018

Two Sonatinas (Pavana del Gallo y el arlequín, p. 23)

I was the passenger of oblivion

Returning from a journey without memory

across unknown routes

across forgotten stations

where no one awaited me

I could not open the door out of fear

the bloody jaws of a wolf howled inside me

All the islands, all the clouds

could have been my towers

But there was nothing except oblivion

on the walls

Oh! concentric cell whose vast

solitude has gathered in my bones!

I was that traveler who returned from every adieu

leaving behind villages submerged in the snow

Faces lost in the night

When the train covered in stars unloaded

its marvelous cargo

I descended with empty hands

in the middle of moth-eaten bell-towers

my eyes brought deadened visions

from an ancient age

of salt and portents

everything retreated from me

I was submerged in oblivion

But, who summons the ones who are absent?

Open!

Open the doors of the tombs!

II

I was saying: rapture, an azure, the lost silences,

but no one came from the islands and that blue and that

other rapture

were but hymns

of small islands that sparkled from afar

like golden transparencies of green,

as if the presence of desolate clouds

towers of algae and the infinite

that suddenly

comes through the windows

of the abandoned mills.

The blind howling of cats upon the carpets

and dawn falls like a presage

of a rain even more tenuous than the mystery

a layer of frost coating the wire of the fences.

© translation by M. Romo-Carmona, 2018