As a new 3rd-grade teacher in 2001, I remember hearing about the “new” standards being implemented across New York State (and still have one of the original spiral-bound copies of the Reading and Writing standards we were issued sitting with my collection of teaching materials). At the time, we were told the standards would guide our instruction, and were asked to make sure they accompanied bulletin board displays and were incorporated in lesson plans. But we would later find out that the standards had a dual purpose — they were also a measure by which our students would unknowingly come to be defined and by which teachers would be evaluated.

Almost immediately, our students became numbers instead of names; we were conditioned to see our students as digits that either supported or undermined our path toward becoming another “failing” New York City public school.

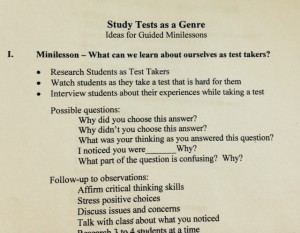

I recently sifted through my teaching materials from that time, and came across a packet for teaching test-taking as a genre. Back in the early 2000s, the balanced literacy model — the method of instruction in which students learn to read and write using real books in a workshop model (as opposed to using basal readers with little to no interaction with their peers) — was just being introduced (or re-introduced) in many public schools. And so we switched from using scripted lessons that were packaged by Harcourt-Brace to using scripted lessons that were packaged by Teachers College, Accelerated Literacy Learners, and America’s Choice. We taught reading and writing via a set of genres — we’d spend a month working on narrative, then move on to informational, persuasive, etc. With the influx of testing awareness, during what we now know as the start of the standardization movement, someone creatively came up with the idea of creating a unit of study around testing. And suddenly test-taking became a genre, too. Eek.

I recently sifted through my teaching materials from that time, and came across a packet for teaching test-taking as a genre. Back in the early 2000s, the balanced literacy model — the method of instruction in which students learn to read and write using real books in a workshop model (as opposed to using basal readers with little to no interaction with their peers) — was just being introduced (or re-introduced) in many public schools. And so we switched from using scripted lessons that were packaged by Harcourt-Brace to using scripted lessons that were packaged by Teachers College, Accelerated Literacy Learners, and America’s Choice. We taught reading and writing via a set of genres — we’d spend a month working on narrative, then move on to informational, persuasive, etc. With the influx of testing awareness, during what we now know as the start of the standardization movement, someone creatively came up with the idea of creating a unit of study around testing. And suddenly test-taking became a genre, too. Eek.

At the time, it made sense — we had to make sure test prep made its way into our instruction so that students felt prepared to take the tests that would, in many ways, determine their futures; however, it gave test-taking the same level of importance as actual literary genres. And sadly, as we’ve seen recently in the media and via personal experience, the standards attached to the Common Core — the latest iteration of learning standards — have created a similar frenzy around what counts as educational success.

Despite my own personal feelings as a literacy specialist that the Common Core provides some truly useful ideas to guide instruction at a variety of instructional levels, I acknowledge that the true problem lies in how the standards are being used and why. At the end of the day, no matter how high we raise the bar on paper, we’re not going to change how well students learn in reality unless we look at the economic, social, and political issues surrounding education. As parents across the country take a stand and keep their children out of school on Monday, November 18, to protest the Common Core State Standards and what they’re doing to public education, I stand in solidarity with their decision to make their voices heard.