Activists from the Elevator Action Group with Rise and Resist took a subway ride with NYCT President Andy Byford on April 13, 2018. The trip illuminated some of the problems with signage, separate fare payment systems, boarding areas, and many other accessibility issues. Byford plans to incorporate accessibility priorities in a comprehensive corporate plan expected to be released in May. (Photo by Erik McGregor)

In January of this year, a group of scrappy subway activists hatched a plan to make a splash at the NYCT Committee Meeting, delivering a gift for the incoming New York City Transit president, Andy Byford, who is in charge of the subways, buses, and Access-A-Ride. The Rise and Resist Elevator Action Group, founded by Jennifer Marie Bartlett in April of 2017, has been staging rallies and protests to gain public awareness of the issue and building a coalition of organizations who share the same access needs. We’ve partnered with CIDNY (Center for Independence of the Disabled, NY), Disability Rights Advocates (DRA), TransitCenter, Straphangers Campaign, and Up-Stand, an organization dedicated to making life easier for pregnant women and families. We created a campaign, Elevators are for Everyone, which highlights the diverse population of people who ride the subway and use elevators every day.

After reading about the wunderkind that so many transit advocates are pinning their hopes on, we were pleasantly surprised when he stated in a press conference that accessibility was one of his top four priorities, each of which has equal importance. After decades of MTA resistance to improve accessibility for disabled New Yorkers, we were optimistic but naturally, skeptical. After all, the MTA settled a lawsuit in the early 1990’s by agreeing to make 100 key stations (of 493 total subway and Staten Island railroad stations) wheelchair accessible by 2020. Today, there are still 13 key stations without elevators. In 2016, Governor Cuomo’s Enhanced Station Initiative set aside close to $1 Billion for cosmetic renovations to 33 stations that did not include elevators and will likely be finished sooner than the remaining key stations. That program ran out of money just a couple of weeks ago. The MTA can complete only 19 stations after the average cost per station went from $28 Million to $43 Million. There was no real explanation or hubbub about the cost overruns. MTA Chairman, Joe Lhota didn’t mention it to the board, saying, “I didn’t think it was relevant to the debate.” The Americans with Disabilities Act requires that when any building undergoes renovations to the entrance that 20% of their budget goes toward making accessibility improvements. Would accessibility improvements at these enhanced stations cost more than $8.6 Million? We have no idea because it’s not really clear if an estimate for elevators was ever made. This is the level of attention the MTA has typically given towards their responsibility as a federally-funded public transit agency to provide service to passengers with disabilities that is “comparable” to passengers without disabilities.

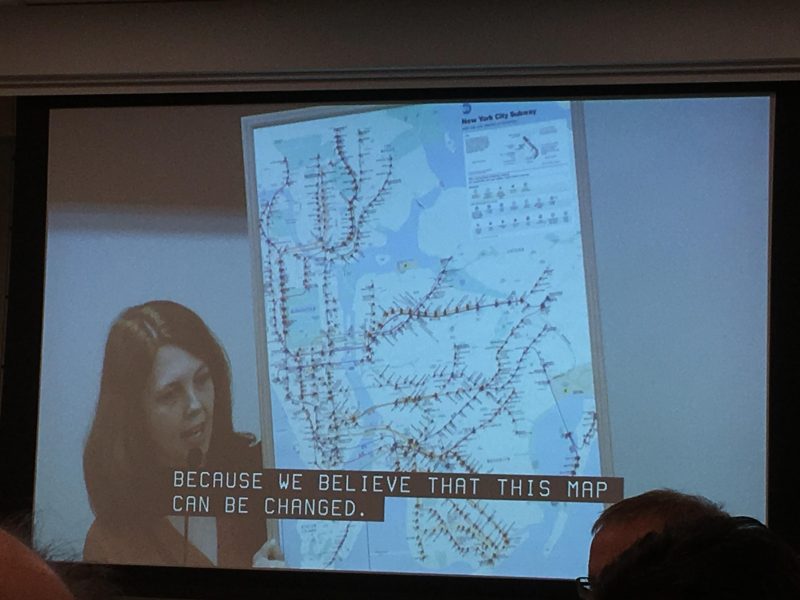

Our plan began to take shape after one of our members had the “crazy idea” to invite him to ride with us to see what it’s like to ride the subway when you can’t use the stairs. After reading a profile on Byford that mentioned the framed subway map on his new office wall, another member suggested that we present him with a life-sized subway map—the version where all of the stations without elevators are erased from the map. We couldn’t find a file large enough to print at that size, so the idea for a corkboard with red pins for inaccessible stations and blue pins for accessible stations was born. On Monday, January 23, we attended the NYCT committee meeting to read our letter to Byford and presented the map during the public comment period.

When we heard back that he was taking us up on our offer to ride the subway with a small group, we scheduled a meeting to decide who would go along with him. We agreed that Jennifer and I would go, but had a dilemma because we wanted at least one wheelchair user to accompany us and nearly everyone in our group was a plaintiff in one or both of two class-action lawsuits against the MTA. The way to enforce the Americans with Disabilities Act, after all, is to file a lawsuit, either on behalf of an individual or group of people (with no possibility of plaintiffs receiving monetary compensation). The Federal Transportation Administration or Department of Justice can also file suit against the transportation agency. It turned out that my friend, life-long advocate, manual wheelchair-user, and frequent subway rider, April Coughlin was not involved and we invited her to join us. We later invited a fourth member to have representation from a powered wheelchair user and woman of color, but she was unable to attend at the last minute.

Reaching an agreement on who would attend this ridealong highlighted to me how delicate the work of doing advocacy can be, especially for issues impacting people with disabilities. I live with Multiple Sclerosis, something that is part of my identity and motivation for the work I do, yet I am perceived as an able-bodied woman. I take a disease-modifying medication and the only symptoms that impact me regularly are muscle spasticity and fatigue. In the 13 years since I was diagnosed, I’ve had four major relapses—when a lesion in my brain becomes inflamed and causes symptoms that vary depending on where it is located. I experienced a minor relapse immediately after the 2016 Presidential election, but my last major relapse occurred almost exactly 7 years ago. That was the worst one, affecting the motor functioning on one side of my body and making it difficult to walk. It happened after a pretty bad ankle sprain kept me off my feet for over a month. It was also the beginning of a slow awakening to accessibility issues, the factor that precipitated my return to school, and eventually led me to the study the issue of accessible transportation for people with disabilities. I suspect that many peg me as a privileged, white, able-bodied savior-type, and I’ve had that suspicion confirmed to me on more than one occasion. I’m committed to being a better ally and expect to continue learning for years to come, but I still find myself explaining why I’m doing this work nearly every time I talk about it with someone new.

There is an important social aspect to public transportation that goes beyond providing access so people can get to opportunities and fulfill their basic needs. Intentions aside, our public transportation system segregates people with physical disabilities into paratransit or through subway entrances designed just for them. On buses—the one on-demand public transit option that is 100% wheelchair accessible—passengers with wheelchairs are made into a spectacle as drivers must ask everyone to wait to board, unbuckle and get out of their seat, eject the passengers sitting in the boarding area, and strap them in with a belt, all before other passengers can board and be on their way. The number of people with disabilities we encounter while using public transportation doesn’t come close to fully representing the percent of the population with those disabilities. Given the current environment, it’s easy to understand if they are discouraged from traveling much at all. People with disabilities need to be comfortable and feel supported when they’re out in public, and the subway is about as public as it gets. Jennifer has pointed this out time and again, at rallies, and occasionally at board meetings, and this was one of her motivations for starting the Elevator Action Group. If people aren’t seen in the public sphere, ending discrimination will take many more years.

Months later, after many follow-up emails by another of our persistent advocates, we finally set a date: Friday, April 13, 2018. Due to Byford’s heavy load of responsibilities, he suggested that we accompany him on his regular commute on the 1 train to the South Ferry station. Since he lives next to an inaccessible subway station, it took a few more emails to figure out a route, which may have been a small lesson in itself. We agreed to meet at Times Square to take the train together, which meant that we didn’t get the chance to show him what it means to “just go to the next accessible station” in a wheelchair. Anticipating a very brief subway ride, we crowdsourced an NYCT Accessibility Wishlist, in case we didn’t have enough time to say everything we wanted to.

Our skepticism, heightened by the early 7:00 a.m. meeting time before any of us had coffee, led Jennifer to ask if he arranged for the elevators to be clean and in working order for our trip. He offered to let us change the route to any other station and surprised us when he said he had several hours until his next meeting so we wouldn’t have to rush. We decided to take the 7 train to Grand Central and transfer to the 4/5 down to Bowling Green, across the street from MTA headquarters. We even stopped for coffee and bagels at GC and talked about Access-A-Ride, among other things. A moment that stood out for us all of us was when Jennifer, whose cerebral palsy affects her speech, ordered her breakfast. The person taking the order addressed Andy to ask what Jennifer wanted. Having experienced this her whole life, she had her response ready, “I can speak for myself.” After we sat down, he made a remark about it and told us he couldn’t imagine regularly receiving that kind of treatment. This moment really said the most about the kind of person he is, and we left our subway ride feeling like we might have an important and influential ally on our side.

He may not have gotten the real sense of trying to get somewhere on a tight timeline, waiting for slow elevators, or encountering broken elevators. I think he still got some good insights and learned a few new things. For instance, auto-gates, the emergency exits that double as a wheelchair entrances, only accept reduced-fare MetroCards. This was brand new information for him. The card reader was not working where we met at Times Square, and April pointed out that she wants to pay the full fare like everyone else. He also noticed that the signage to elevators also needs work and that there weren’t enough accessible areas on the train cars themselves. We were able to deliver our wishlist, and hope to continue the conversation. I believe he will continue to listen to people with disabilities. For now, we’re saving our skepticism for the uphill battle to secure funding and keep accessibility high on the MTA’s priority list.

Here’s a link to photos from our subway ride, by the intrepid photographer, Erik McGregor. You can support our cause and buy your own Elevators are for Everyone t-shirt, and if you want to get more involved, request membership to our Google group.

Here’s a link to photos from our subway ride, by the intrepid photographer, Erik McGregor. You can support our cause and buy your own Elevators are for Everyone t-shirt, and if you want to get more involved, request membership to our Google group.

Keep at it!

Andy Byford is a star!! I attended a meeting at Rutgers Church he gave, put together by Assemblyperson Linda Rosenthal. If anyone can get it done, with all the bull that’s out there surrounding the MTA, it’s him!

Meanwhile, it seems really out of the question impossible that someone in a wheel chair would be able to use the subway during rush hour. The chaos on the platforms and inside the trains with the overcrowding is horrendous.

I would hope that the dedicated bus lanes that are being put into effect on some routes might help in assisting people with disabilities get to their destinations more conveniently and on time?!

It is tough, but people still do it. If there were more accessible stations and elevators were working reliably, more people would benefit. Byford has already made progress on elevator maintenance, and has ambitious plans to make the system as fully accessible as possible, but Governor Cuomo doesn’t seem to support his plan.

Dedicated bus lanes are great and will help, but the buses are already crowded, which makes travel difficult for wheelchair users. They may get stuck waiting for the next bus when other passengers won’t leave the designated seating area, or when other people with disabilities are occupying those spaces. Bus travel is also difficult between boroughs, and may require more than one transfer, which means an additional fare. Express buses are more than twice the standard fare and have frequent issues with lifts that don’t work.

Paratransit has many issues, the main ones being the need for 24-hour advance planning, a 30-minute “on-time” window for pickups and drop-offs, and excessively long trips. I know people who spend an entire day to go to a doctor’s appointment because they have to add time on both ends, and sometimes they’re still late.