Elizabeth Foley

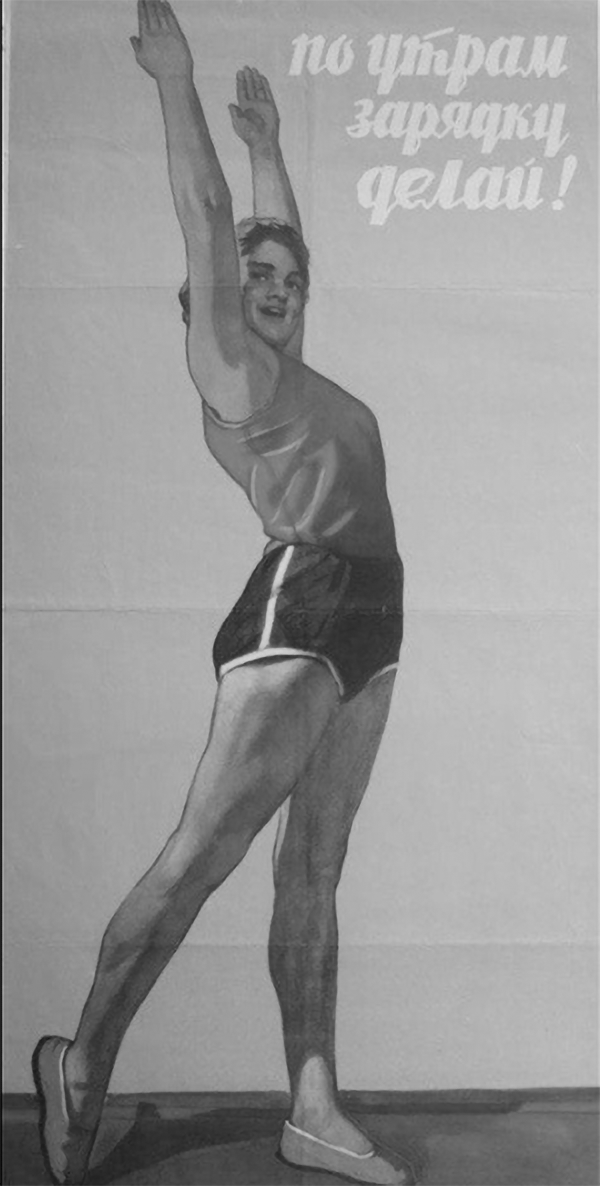

Americans are lectured constantly for our failure to exercise. We’re regularly updated on how obese and sedentary we collectively are, then reminded by authorities that these traits simultaneously make us deserving heart attack risks and moral failures. Working out, if only we would do it, would make us healthy, wealthy and wise. If we could manage to demonstrate at least one of those attributes, American society would be forced to acknowledge our value as citizens. Exercise would make us morally as well as physically fit. Why on earth don’t we just buckle down and do it?

Speaking as someone who has worked out regularly for over twenty years, I completely understand why Americans do not exercise. Far from making me a cheerleader for exercise, or a believer that it’s a universal panacea for what ails us, working out for so many years has intensified my empathy for those who don’t manage to do it. Working out is an existential business at the best of times, occupying a psychic territory whose permeable borders are contiguous with those of both sex and death. Exercising entails regular confrontations with one’s own physical ability, desirability, and mortality. Some days, inevitably, the outcomes of this confrontation are fearful and depressing. And not only is regular exercise challenging both physically and psychologically, it is political in ways that are rarely acknowledged by its advocates.

Let’s start with the class implications of exercise. Working out is a middle-class behavior, and the American middle class has been shrinking for thirty years or more. Where it still exists, the middle class is an increasingly harassed and beleaguered group, one far less amenable than it once was to the traditional values of investing in the future and delaying gratification accordingly. Working out means voluntarily submitting yourself to short-term suffering to enhance your health over the long term, in the same way that a 401K plan takes bites out of your present-day income that will, if all goes well, be returned to you as a nest egg later in life. In a world where fewer and fewer Americans have 401Ks, however, it’s irritating to be told to treat our own bodies as metaphorical pension plans, as if good health habits alone could act as our safety nets in retirement. The struggle to stay economically and professionally afloat, and to meet the demands of employers, families, professors, and other claimants on our time, means that many Americans are already in a fairly constant state of involuntary suffering. So why on earth would we voluntarily take on more in the service of a future that seems increasingly unlikely to arrive?

Also relevant in a landscape of rampant income inequality is the fact that working out itself costs money. Gyms, as useful as they are to some members, act as money pits for many others, operating with a business model that assumes many people will pay for services they won’t use but will feel guilty enough about the gap between their aspirations and reality that they’ll keep on paying to expiate that guilt. If you do use your gym, you will likely find yourself laying out additional money (optimizing your investment, you might say) for personal fitness accessories like tricked-out water bottles, yoga mat carriers, or fitness trackers, to say nothing of clothing. The real essentials of workout clothing are appropriate shoes and the garments that are necessary to support whatever dangly parts of your body you don’t want bouncing around during your workout, but if looking cute motivates you to work out more, which it might, you may find yourself buying a lot of stuff beyond those basics. If you exercise outdoors, an option that offers unique benefits and pleasant distractions, you will need different clothes for different kinds of weather. If you vary your workout activities, as we are frequently advised to do, you may need to own more than one type of shoe. If you work out regularly at just one activity, you will be alarmed at how quickly your single pair of shoes will wear out and need to be replaced (generally at over a hundred dollars a pop). All of these issues make exercise a complicated prospect for people who are less than comfortably middle class.

Also relevant in a landscape of rampant income inequality is the fact that working out itself costs money. Gyms, as useful as they are to some members, act as money pits for many others, operating with a business model that assumes many people will pay for services they won’t use but will feel guilty enough about the gap between their aspirations and reality that they’ll keep on paying to expiate that guilt. If you do use your gym, you will likely find yourself laying out additional money (optimizing your investment, you might say) for personal fitness accessories like tricked-out water bottles, yoga mat carriers, or fitness trackers, to say nothing of clothing. The real essentials of workout clothing are appropriate shoes and the garments that are necessary to support whatever dangly parts of your body you don’t want bouncing around during your workout, but if looking cute motivates you to work out more, which it might, you may find yourself buying a lot of stuff beyond those basics. If you exercise outdoors, an option that offers unique benefits and pleasant distractions, you will need different clothes for different kinds of weather. If you vary your workout activities, as we are frequently advised to do, you may need to own more than one type of shoe. If you work out regularly at just one activity, you will be alarmed at how quickly your single pair of shoes will wear out and need to be replaced (generally at over a hundred dollars a pop). All of these issues make exercise a complicated prospect for people who are less than comfortably middle class.

I grew up middle class and have been lucky enough to stay that way into adulthood, which may explain my susceptibility to the debatable belief that exercise is an inherently meritorious practice. It may also explain my willingness to invest money in exercise: whatever middle-class guilt I feel about spending money on non-necessities is abated by the idea that exercise is a virtuous thing to spend money on. I haven’t belonged to a gym for a long time, but over the years I’ve accumulated a fair amount of home exercise paraphernalia: a mountain bike and accessories (tire pump, hanging rack, etc.); a mini-trampoline that is neither budget nor top-of-the-line; a set of replacement cords for the trampoline when the first set wore out; various sets of free weights; a set of wrist and ankle weights; a small library of fitness DVDs; multiple generations of screw-in headphones for running; a gym bag; a Master lock with a combination; a Master lock with a key; multiple sports watches; a hoop; an exercise ball; a foam roller; a heavy-duty yoga mat for home use; a yoga band; and a jump rope. With the exception of the jump rope, which is inconvenient to use both indoors and outdoors and which exacerbates my exercise-related stress incontinence I actually use these items regularly. Still, though, I am constantly considering new additions to the collection. Following a recent episode of tendonitis that forced me to scale back my cardio routine for several months, I’ve entertained idle fantasies about buying a Peleton bike – a problematic idea not only because it is such an elitist fitness item, but because accommodating one would require me to move into a bigger apartment.

In the meantime, I remain a model middle-class exerciser, retaining those naive convictions that virtue will be rewarded, pain will bring gain, and investments in the fitness sector of the American economy will bear dividends for my personal health. With money and the will to exercise in adequate supply, my chief problem has become one of time (which, as we know, is just money in a different guise). When Americans complain that they don’t have time to work out, they are actually not kidding. They may, technically, have time somewhere among the sixteen or so waking hours of every day to fit in a workout, but not all waking hours are equally usable for every kind of task. One reason I am an inveterate morning exerciser is simply that there are fewer demands on my time in the morning. My boss doesn’t expect me to be answering emails at 6:30 a.m., nor do I have meetings, classes or social obligations scheduled at that hour (For parents with school-age children, however, this calculus may be meaningless). If you exercise later in the day, you are likely to be all too aware of the million competing things you could quite legitimately be doing with that time. You’ll also probably have to exercise while your lunch or dinner is still digesting. You might have to shift from public-facing clothes, hair, and makeup to gym mode and maybe even back again. It’s much easier, in my experience, to transition from pajamas and overnight fasting into workout mode and then to shower and get ready to face the world only once a day.

In the meantime, I remain a model middle-class exerciser, retaining those naive convictions that virtue will be rewarded, pain will bring gain, and investments in the fitness sector of the American economy will bear dividends for my personal health. With money and the will to exercise in adequate supply, my chief problem has become one of time (which, as we know, is just money in a different guise). When Americans complain that they don’t have time to work out, they are actually not kidding. They may, technically, have time somewhere among the sixteen or so waking hours of every day to fit in a workout, but not all waking hours are equally usable for every kind of task. One reason I am an inveterate morning exerciser is simply that there are fewer demands on my time in the morning. My boss doesn’t expect me to be answering emails at 6:30 a.m., nor do I have meetings, classes or social obligations scheduled at that hour (For parents with school-age children, however, this calculus may be meaningless). If you exercise later in the day, you are likely to be all too aware of the million competing things you could quite legitimately be doing with that time. You’ll also probably have to exercise while your lunch or dinner is still digesting. You might have to shift from public-facing clothes, hair, and makeup to gym mode and maybe even back again. It’s much easier, in my experience, to transition from pajamas and overnight fasting into workout mode and then to shower and get ready to face the world only once a day.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommends two and a half to five hours of moderate exercise a week or one and a quarter to two and a half hours of vigorous exercise a week, plus two sessions of strength training that each work every major muscle group. My current personal goal is three thirty-minute sessions of high-intensity cardio per week, which is (barely) within HHS recommendations, plus – because I’m a woman over forty and middle-aged loss of muscle tone is real – three, rather than two, sessions of strength training per week. These latter sessions, in practice, take about forty minutes each, but for convenience’s sake, let’s pretend they take thirty. That theoretically means six half-hour workouts per week (really seven), or three hours (really three and a half) total. Everyone, including me, should theoretically have three (and a half) hours a week to fulfill such relatively modest exercise goals.

The time you spend working out, however, is only a portion of the total time you will actually need in order to exercise. Without even including the time it takes after getting up in the morning to perform essential pre-workout steps like caffeinating, rehydrating, and allowing your bowels to move, it takes time to get dressed, triple-tie your laces (I’ve learned the hard way never to neglect this step), manipulate your hair so it’s out of your face, brush your teeth (because coffee-mouth is a distraction during exercise), and assemble the necessary accessories (you did remember to charge your phone for your run, right? And your playlist is just how you want it, right?). Then there’s the five to ten minutes you spend procrastinating because you don’t particularly want to work out and there is always some small administrative or domestic task you decide you can and should do before you start your workout, or some piece of information you need to look up online so you can think about it during your workout. After all these years, I’ve stopped fighting this procrastinatory interlude; it’s become part of the process and may even be a positive thing, since it lets me consider, then reject, the idea of breaking my commitment to work out. Once you overcome your procrastinatory impulse, you then need to get to your exercise location. Are you going to the gym? Add commute time. Are you going for a run in your own neighborhood? Personally, it takes me an extra two and a half minutes just to get from the door of my apartment to the street, and I don’t even live on an upper floor. (Getting a bike down to the street takes even longer, and biking in general is so unpredictable – mechanical issues, traffic – that it’s really only feasible for me on weekend mornings before the streets and parks fill up with people and vehicles.) Then, of course, you need a few minutes to warm up and/or stretch.

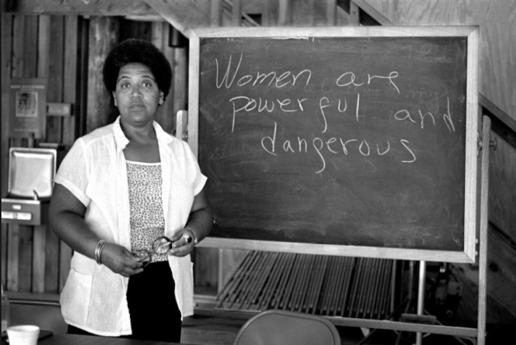

Once you finish your workout itself, you’re not done, not by a long shot. I don’t stretch after a workout – you’re kidding me, right? I’m late to work already! But lots of people do, and I may eventually be forced to join their number. You also, without question, need to hydrate (at least eight ounces of water for every 20 minutes of activity is my rule) and get out of your sweaty clothes, two tasks I do simultaneously to save time. You need to track your workouts — at least, I do, or I’ll forget what I did and how often I did it. Then you’re in the shower, getting clean and ready to go out into the world. This is where gender expectations slip into complicate matters. The time you need for exercise includes the prep time for exercise, the exercise itself, and the cleaning and grooming oneself after exercise. But the final leg of that process almost always takes longer for women than for men because of our hair and makeup routines and more complicated wardrobes, which adds a backwards-and-in-heels aspect to women’s workouts. This disparity applies to a certain extent even without exercise, but adding exercise makes it harder to take grooming shortcuts: you might be able to get away with not washing your hair after exercise if it’s winter and all you did was strength training, but once your hair hits a certain level of sweatiness you’re on the hook for shampooing, conditioning and styling, plus whatever skin preparation and makeup application you normally perform after showering. The more often women work out, the more this already unequal share of grooming labor increases. And the burden is even greater for black women, who already may be putting in several multiples of the time that white women spend on their hair in order to meet racialized expectations of what “professional” and/or “feminine” black hair should look like. It’s no good claiming these demands aren’t real or binding in a world where black women can still be expelled from high school or publicly chastised by their fellow members of Congress if the powers-that-be decide their hair looks wrong. So black women who commit to regular exercise have an especially complex set of logistical hurdles to jump through.

Once you finish your workout itself, you’re not done, not by a long shot. I don’t stretch after a workout – you’re kidding me, right? I’m late to work already! But lots of people do, and I may eventually be forced to join their number. You also, without question, need to hydrate (at least eight ounces of water for every 20 minutes of activity is my rule) and get out of your sweaty clothes, two tasks I do simultaneously to save time. You need to track your workouts — at least, I do, or I’ll forget what I did and how often I did it. Then you’re in the shower, getting clean and ready to go out into the world. This is where gender expectations slip into complicate matters. The time you need for exercise includes the prep time for exercise, the exercise itself, and the cleaning and grooming oneself after exercise. But the final leg of that process almost always takes longer for women than for men because of our hair and makeup routines and more complicated wardrobes, which adds a backwards-and-in-heels aspect to women’s workouts. This disparity applies to a certain extent even without exercise, but adding exercise makes it harder to take grooming shortcuts: you might be able to get away with not washing your hair after exercise if it’s winter and all you did was strength training, but once your hair hits a certain level of sweatiness you’re on the hook for shampooing, conditioning and styling, plus whatever skin preparation and makeup application you normally perform after showering. The more often women work out, the more this already unequal share of grooming labor increases. And the burden is even greater for black women, who already may be putting in several multiples of the time that white women spend on their hair in order to meet racialized expectations of what “professional” and/or “feminine” black hair should look like. It’s no good claiming these demands aren’t real or binding in a world where black women can still be expelled from high school or publicly chastised by their fellow members of Congress if the powers-that-be decide their hair looks wrong. So black women who commit to regular exercise have an especially complex set of logistical hurdles to jump through.

Speaking only for myself, I find that between preamble, actual workout time, and post-workout ablutions, “working out for thirty minutes” actually requires something approaching two hours. As I’ve gotten older, too, the time commitment has increased. My hair has become extremely tangle-prone with age and sheds at every step of washing and styling, requiring extra time to manage. My skin is drier, such that three seasons out of four, I can’t skip moisturizer or body lotion after showering unless I want to sit itching at my office desk two hours later. When I started exercising in my twenties, I didn’t regularly wear makeup; now I do. All this has gradually added an extra ten to fifteen minutes to my daily post-exercise routine, or roughly an hour and a half per week. Which means that my modest-sounding three (and a half) hours of exercise per week are actually embedded within a fairly non-negotiable twelve- (really fourteen-) hour block of committed time per week.

If you are a regular exerciser, you will eventually find yourself grappling with similar philosophical and logistical questions of time, such as “What is the shortest unit of workout time worth getting into workout clothes for?” Fifteen minutes, really, but I’ve done it for a ten-minute ab routine. “How often should I wash my workout clothes if I’m working out near other peoples?” My laziness on this point, along with my stress incontinence, is why I don’t usually work out in the vicinity of other people. “If I don’t want to wash my workout clothes as often as new parents wash diapers, how many multiples of each item of clothing do I need to invest in?” At least two, especially if you want to work out in one set of clothes while washing others, and you should buy them in different colors or styles so that you can more easily distinguish the clean ones from the dirty. “If a blizzard is coming tomorrow morning, do I need to grab a run today even though it was supposed to be my rest day?” If there will be accumulation and/or ice lasting for several days, then yes, you probably do. Working out while traveling presents an additional set of problems. Athletic shoes take up lot of space in your suitcase, and “optional” after-dinner cocktails with colleagues on the first night of a conference followed by a 9:00 a.m. start time the next day will probably wreak havoc on your plans to work out. If you work out in the hotel gym, you’ll waste precious time trying to figure out how to use the unfamiliar machines. If you escape for a run, especially in the semi-darkness of the early morning, you might not know where the safe routes are, or you might get lost, or an unaccustomed climate or altitude might make you sick afterward. If you’re staying with family or friends who don’t work out, or don’t work out in the ritualistic way that you do, are they going to resent your complicating their schedules by going for a run or beginning the morning with 90 minutes of yoga? Probably. Among other things, you’re making them feel guilty for not doing the same.

This seems like a good time to point out that exercise is not the only time-consuming health-related activity that Americans are regularly accused of not doing enough of. As a nation, we are also chronically, even dangerously, short on sleep, with a third of us regularly getting less than the minimum of seven hours of sleep a night recommended by the Centers for Disease Control. Despite concerted efforts to improve my sleeping habits, I am in this category. On a typical work night, I get six to six and a half hours of sleep and might make seven hours on the weekends. Were I to get seven hours of sleep a night in addition to performing two hours of exercise-related activity a day, while also spending eight hours a day at work, that would already account for seventeen hours of my twenty-four. Add the two hours I spend commuting to and from work on the subway each day, which double as my graduate-student reading time, and I’m up to nineteen hours. So five hours a day are what remain for administrative and domestic tasks, cooking and eating meals, reading news to keep up with the daily malfeasances of the current administration, leisure activities, and – oh yes – revising my master’s thesis (I can hear the peanut gallery already: “Why aren’t you revising your thesis on the train?” Well, sometimes I do. But this is not the easiest thing to manage when you can’t get a seat, or when you’re trying to check quotes from non-digital sources). Since the ten hours a day I spend working or commuting are fixed, and since a certain minimum of administrative, domestic and food-related labor is also necessary to keep the hamster wheel of life turning, the rest of my existence is shaped by a constant struggle for pre-eminence in my schedule among sleep, exercise, and all other semi-negotiable activities. In practice, I find that it is nearly impossible to simultaneously get “enough” sleep and “enough” exercise unless I resign myself to sacrificing the last remnants of my leisure time to sleep; otherwise, exercise almost always occurs at the expense of sleep or vice versa. And I don’t even have kids!

Although I could never have continued working out for decades if the process didn’t have its satisfactions, I would definitely not describe exercise as “fun.” I also reject the characterization of workout time as “me time” promulgated by celebrities and other professionally fit people who are trying to appear far more casual about their long and involved exercise routines than they actually are. (“Me time” should be time during which you are breathing at normal rates; the only exception I’ll allow to this rule is sex.) Nor is it really accurate to categorize working out as a “leisure” activity, even though it occurs in our so-called downtime. In point of fact, exercise is labor: it’s housekeeping for the body, and all the arguments that feminists and Marxists have made over the centuries about housekeeping as a form of unpaid labor also apply to exercise. In both cases the labor is not officially required, but there are significant social and health consequences attached if it doesn’t get done, and the performance of this labor tends to fall differently, and usually more heavily, on women than on men.

Although I could never have continued working out for decades if the process didn’t have its satisfactions, I would definitely not describe exercise as “fun.” I also reject the characterization of workout time as “me time” promulgated by celebrities and other professionally fit people who are trying to appear far more casual about their long and involved exercise routines than they actually are. (“Me time” should be time during which you are breathing at normal rates; the only exception I’ll allow to this rule is sex.) Nor is it really accurate to categorize working out as a “leisure” activity, even though it occurs in our so-called downtime. In point of fact, exercise is labor: it’s housekeeping for the body, and all the arguments that feminists and Marxists have made over the centuries about housekeeping as a form of unpaid labor also apply to exercise. In both cases the labor is not officially required, but there are significant social and health consequences attached if it doesn’t get done, and the performance of this labor tends to fall differently, and usually more heavily, on women than on men.

Some companies, interested in avoiding the financial and productivity costs of employing people who aren’t in optimal health (costs associated with absenteeism, for instance, or of accommodating employees with chronic or catastrophic illnesses), have actually begun to incentivize employee exercise in meaningful ways – and by “meaningfully incentivize” I don’t mean adding a few gym machines to an unused conference room. I mean actually compensating employees financially and/or allowing them to work out during work hours. But there’s nothing in corporate culture that obligates companies to take this sort of long view of employees’ health, and plenty of forces work against it. The older I get, the more I wonder whether American employers as a whole don’t rely on the increasing physical obsolescence of aging employees, who can conveniently be docked or fired for declining performance at precisely the moment when they would otherwise become more expensive to retain. I’m also skeptical about whether it truly promotes work-life balance to expand the list of activities you perform in the close company of your co-workers, people with whom you already spend more time than with your family and with whom you may already feel obliged to socialize over lunches and after hours. The power dynamics of company gyms can be uncomfortable, too. My own workplace has a small one-room gym with several cardio and weight machines, but in over a decade of working there I haven’t used it more than five or six times. If our senior staff want to appear democratic and approachable by sweating amongst the proles in ratty T-shirts and flab-revealing tights, that’s their prerogative, but I don’t need that kind of vulnerability in front of them – especially if I’m working out instead of finishing that thing I owe them.

With exercise, as with any other private activity we do that carries social implications, it is nearly impossible to cleanly separate the part of it that we do for own benefit from the part that we do for the benefit of others. On the one hand, tending to one’s own health is an essential act of self-defense in a politically and economically hostile world. “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence; it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare”: this was Audre Lorde’s classic expression of the notion that the survival of marginalized people in the teeth of oppressive systems can constitute a form of subversion and a base for further resistance against those systems. But what about those of us whose lives are protected only insofar as we are fodder for those systems? Good health, under these circumstances, may simply mean that we can offer ourselves up as a higher caliber of fodder. When I roll into work late after having made the executive decision not to abridge my workout, and when I know that my co-workers are noticing my lateness even if they don’t comment on it, I want to protest, “Don’t you understand? I’m doing this for you” – doing it, in other words, so that I can maintain the physical and mental energy to perform optimally at work and still have something left over for my academic obligations, my personal tasks, and myself. It’s the “for myself” part that is the rub, of course – at the end of the day, institutions tend to be concerned only with what their members are doing to serve the institution. They regard all other activities as irrelevant, if not actually invalid, usages of time. It then becomes very easy for institutions to write off activities like exercise as purely personal and voluntary on the part of individuals, when in fact they are forms of performance enhancement that contain an element of service to the institution. Since I’m female, I am especially vulnerable to having my exercise commitment ascribed to vanity (“she’s just trying to be thin”), with no institutional acknowledgment of the fact that it behooves me professionally to maintain a certain kind of appearance and – particularly in my current moment of professional stagnation – to create ambiguity about my age by appearing younger than I am.

Speaking of which, exercising when you’re no longer in the prime of youth is a whole set of concerns unto itself. The Narnian exercise math of middle age, in which you burn calories in an alternate dimension that feels completely real, but are returned to everyday life after your workout to find the status quo unchanged, has forced me to reckon with the purpose and meaning of my exercise habit. In your twenties and into your thirties, exercise can stand alone as a means of weight control, absorbing all manner of dietary sins. But as you age, weight can no longer truly be controlled anywhere except at the source: your diet. Furthermore, as you get older, your body’s ecosystem steadily contracts, making it more vulnerable to a certain kind of butterfly effect. Not only does exercise no longer solve other physical problems for you, but mistakes of diet or sleep will instantly – and I mean within hours – impact your ability to work out at all. And in moments of hormonal siege or transition, your body will change its definition of what constitutes a “mistake” almost daily. You may then find yourself frantically adjusting your diet and sleep patterns simply to enable yourself to keep working out. In middle age, too, new fears of overexertion have begun to overlap with my lingering fear of underexertion, suffusing the whole enterprise of working out with anxiety. The old coach’s refrain “Just push through it” may now be very wrong advice, and on the all-too-frequent mornings when workout time arrives to find me feeling less than fantastic, I am often genuinely unsure whether exercise will right the ship or spring new leaks in it. I can think of two women in American public life whose husbands have died on or near treadmills in the last few years, and youthful complacency no longer protects me from the fear of such things. Increasingly, I feel that the only solution is to come to my workouts already in good shape, as if a practice workout were necessary to qualify me for the real thing.

If exercise is causing me this much angst, you may ask, why do I continue to do as much of it as I do? After all, by my own admission, it’s one of the commitments in my life that is negotiable, even optional. But how optional is it, truly? The New York City subway system, or any mass transit system, requires a certain level of physical fitness, with its endless stairs and frequently malfunctioning escalators. As a student with a long commute, I must remain physically fit enough to do my reading and other coursework standing up, if necessary. As a traveler who often uses mass transit to get to the airport or to Penn Station, I must be able to lug a suitcase up stairs and through turnstiles. I live alone, so I must remain agile enough to change ceiling-suspended light bulbs, scrub floors, rub lotion into my own back, zip up my own dresses, and pull off my knee-high snow boots without having a heart attack. When I was a kid, my mom had recurring back problems, which motivated me to find ways to avoid that fate. Middle age, therefore, seems like the worst possible time to stop doing ab exercises to strengthen my core. On a darker note, my dad has developed some kind of undiagnosed dementia that includes recurring “mini-strokes” which temporarily impede his speech. Half of my DNA comes from him, and exercise is a potential opportunity to intervene in the expression of that DNA. Do I really want to give up that opportunity? More generally, do I really want to acquiesce more than is absolutely necessary in my own obsolescence and decline?

If exercise is causing me this much angst, you may ask, why do I continue to do as much of it as I do? After all, by my own admission, it’s one of the commitments in my life that is negotiable, even optional. But how optional is it, truly? The New York City subway system, or any mass transit system, requires a certain level of physical fitness, with its endless stairs and frequently malfunctioning escalators. As a student with a long commute, I must remain physically fit enough to do my reading and other coursework standing up, if necessary. As a traveler who often uses mass transit to get to the airport or to Penn Station, I must be able to lug a suitcase up stairs and through turnstiles. I live alone, so I must remain agile enough to change ceiling-suspended light bulbs, scrub floors, rub lotion into my own back, zip up my own dresses, and pull off my knee-high snow boots without having a heart attack. When I was a kid, my mom had recurring back problems, which motivated me to find ways to avoid that fate. Middle age, therefore, seems like the worst possible time to stop doing ab exercises to strengthen my core. On a darker note, my dad has developed some kind of undiagnosed dementia that includes recurring “mini-strokes” which temporarily impede his speech. Half of my DNA comes from him, and exercise is a potential opportunity to intervene in the expression of that DNA. Do I really want to give up that opportunity? More generally, do I really want to acquiesce more than is absolutely necessary in my own obsolescence and decline?

The upshot of these considerations is that continuing to exercise seems more important than ever. In my more frustrated moments, I promise myself that if it keeps getting harder to figure out what I should be doing and how often I should be doing it, I will hire a trainer to help me, someone who could share the labor of researching and planning my workouts and who could provide emotional support for the psychologically taxing aspects of exercise. If I looked hard enough, I could probably find some arrangement I could afford and that wouldn’t require me to join a gym. But another part of me is deeply reluctant to take that step. It’s hard not to feel that a trainer would be one more actor in my life who thought his or her needs and demands should take priority over all others, one more person who would say patronizingly, when I failed to go that extra mile to excel within their domain, “Well, I guess you just don’t care about this and are not committed to it.” A trainer would be one more authority figure against whom I would be constantly tempted to rebel, one more person saying “Try harder/Do more/You’re responsible for your own fate/Just be positive/The system would work for you if only you’d adjust your attitude.” A trainer would not be tolerant of my cynical neo-Marxist theories about how a fitter class of worker bees just increases productivity for the CEOs of the world – in no small part because a trainer is an entrepreneur him- or herself, a provider of lifestyle services to the wealthy and those who aspire to wealth, a hustler making bank off Americans’ poor health and unhappiness with our bodies. In this sense, hiring a trainer would mean admitting that the system doesn’t work, that staying in shape is too hard for Americans to do without help, that good health is a class luxury like practically everything else.

“The system,” of course, is not inclined to critique its own ideology or underlying agendas; systems rarely are. But where does the ritual exercise-scolding of Americans come from? First and foremost, it comes from the government–specifically, the aforementioned Centers for Disease Control and the Department of Health and Human Services, each of which periodically issues updates on the severity of our national sloth problem or guidelines on how much and what kind of exercise Americans should be doing. The CDC and HHS have each been compromised in the Trump era. The CDC was forced to fold a program studying the health impacts of climate change into another unit and remove all references to climate change from its website and literature, while Trump’s HHS is led by Alex Azar, who tripled the drug prices of the pharmaceutical giant Lilly when he was its CEO and who is now imposing an overt anti-abortion agenda on HHS’ work. Trump is nevertheless trying to significantly cut the budgets of both agencies. Given these facts, if you wanted to categorically give the finger to all health advice issuing from Trump’s government agencies, I definitely wouldn’t argue with you.

More to the point, however, is the larger hypocrisy of a ruling political party that lectures individual Americans about their health choices while spearheading a nine-year national effort to strip health insurance from about 20 million Americans. Republicans’ sixty-odd legislative attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act without offering a backup plan – to say nothing of the current administration’s executive efforts to depublicize, denature and otherwise cripple the ACA – go well beyond acts of mere political retaliation. Rather, they are a gleeful display of public sadism, a celebration of the illness and death that, in the Republican view, are rightly to be visited on anyone with the nerve to turn to government for any kind of enhancement of his or her well-being. Under the circumstances, Republicans have forfeited any right to tell Americans anything whatsoever about their health.

The current president, of course, also embodies the assault on health in his personal choices, not just his policy, which I suppose at least makes him less of a hypocrite than workout fiend and would-be ACA slayer Paul Ryan. I’m not among those who hopefully speculate that Trump’s terrible eating habits and refusal to do any exercise more strenuous than golf will bring on a fatal health crisis while he’s in office. I think the man is an inverse Keith Richards who will live forever, but without putting anything pleasurable or aesthetically valuable into the world, save perhaps the mockery he inspires among decent people. In his health and lifestyle choices, as in nearly everything else, Trump represents an anti-Obama backlash originating with those who passionately resented being told by Michelle Obama that they might want to eat some vegetables or do a few pushups from time to time. Like Trump, however, the Obamas practiced what they preached, and it can’t be said that the most visibly fit First Couple in modern memory were suggesting that Americans do anything that the two of them weren’t already doing with alacrity themselves. From what I’ve read, both Obamas worked out for an hour or more nearly every morning in the White House gym and encouraged their staff to make use of their trainer, even offering to foot the bill for particularly reluctant aides. And while Michelle, a habitual, early-to-bed, early-to-rise exerciser, did apparently support her workouts with a full night’s sleep, her husband often got by on less than six hours a night after working or reading past midnight. What makes Obama’s presidential schedule even more astonishing is that he is apparently not a coffee drinker! The idea of leading a nation for eight years without caffeine is enough to make me blanch, but to throw in a daily hour of exercise on top of it? I have absolutely no idea how he managed that.

At some point during Obama’s second term – it must have been after Michelle released that workout clip of herself nimbly jumping rope, doing plyometric jumps, kickboxing, and generally not going on autopilot for a single moment – this information actually began to haunt me. When I’m down on my yoga mat doing weighted leg lifts in the early hours, I often find myself thinking with dread about the politically delicate or offensively time-wasting meeting I have at 10:30 that morning, and wondering why my life seems like such an endless series of unhappy obligations. But at least my 10:30 is not a conference call with Kim Jong Un, and at least Fox News will not produce a week’s worth of news segments attacking me for hypocrisy if I appear in public with my biceps looking marginally less defined than they did two months ago. Every single day that the Obamas were in the White House was more stressful than whatever day I have in front of me, yet there they were voluntarily suffering in the gym at the beginning of it. The Obamas are older than me and are involved parents on top of everything else, so rationalizations of slacking off based on those considerations don’t work either. It seems, in this light, that there is no excuse for the non-presidents among us not to meet each and every one of our unhappy obligations.

And yet, most of us being less than superhuman, Americans continue to bail on our obligation to stay in shape, either for ourselves or for others. If the U.S. government as a whole sincerely wanted to make it easier for Americans to get enough exercise, there are things it could do, beyond lecturing us for our lack of fitness, to make that outcome more achievable. It could provide a universal basic income, so that people might be able to save up for a decent pair of athletic shoes after their rent was paid and their groceries purchased. It could provide universal high-quality child care, so that parents would have more time for a distraction-free workout. And it could incentivize structural changes to the economy that would re-normalize a forty-hour work week, as opposed to the 44-hour one that Americans typically work now. (And honestly, even forty hours a week at most jobs is too much, as most Western European nations already know.)

I don’t see any great eagerness on the part of the government to do any of these things, even if the current freshman class of Congresspeople appears to have some radically sane notions of what might constitute a livable quality of American life. I don’t notice a widespread willingness among American employers to hire enough people to sensibly redistribute existing workloads, although cheap rhetoric about work-life balance is ever-present. If the government and the corporate sector aren’t prepared to lift a finger to make it easier for Americans to exercise, the least they could do is get out of the way of those who are already trying. And if they aren’t even willing to get out of the way, the least they could do is stop guilt-tripping people who are already overburdened. If people or institutions actually want to be of help to Americans struggling to manage the structural problems and unrealistic expectations that shape American life, then for the love of God, let them take concrete steps to actually be of help: everything else is just concern-trolling.

Comments by Zammataro