William J. Lorenzo

I come from a family of educators. I don’t have an especially large family, but I have relatives who teach high school, grade school, and Sunday school, in addition to four who teach at various colleges and universities. Of these four, three were never able to attain full-time status at their respective universities, regardless of their experience, expertise, intelligence, and merits. I admire the work they do and their commitment to it. I often contemplated joining the ‘family business,’ so to speak as early as high school. I went to a Jesuit college preparatory school which was in many ways superior in educational quality to most colleges and universities. It was there that I was able to take liberal arts and humanities courses in my senior year. I worked hard and graduated at the top of my class, then went on to graduate summa cum laude (and was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa) from CUNY’s Macaulay Honors College, and eventually The Graduate Center. After I graduated from the Grad Center, one of my relatives informed me of an impending vacancy at one of the colleges at which he worked. Before his colleague retired, I asked the chairperson of the art history department if she would consider me for a position teaching a few courses. The next thing I knew, I was officially hired by a local private arts college in Brooklyn, teaching several film history courses.

I had heard of the horrors of adjunct/part-time college teaching from family and friends at the Grad Center, but nothing could have prepared me for what I was about to experience. Even a seminar course on the history and future of higher education as an undergrad didn’t prepare me for how bad it proved to be. Never could I have imagined how broken our higher education system is, even at a private college. To shine more light on the injustices of part-time college teaching and prepare anyone who reads this for what might occur (depending of course on the integrity of the administrators at the college or university where you work), I would like to share with prospective and current educators the experiences I have encountered.

After teaching my first semester, there were a few students who failed the course I taught. I consulted with the chairperson who hired me, and she agreed that all failures were warranted. Two of the students began to immediately complain about their grades. My chairperson stood her ground (as did I), and the students were informed that their grades would stand. Over the summer of 2017, my chairperson stepped down as head of the department and a new chair took her place. Within weeks of taking over the position, he called me into his office for a meeting. Over the interim weeks, one of the failing students had involved another chairperson (from his department of study) and the head of advisement in his complaint process. I would also later be mistakenly forwarded the poison-pen character assassination email written by the failing student to the new chairperson. The new chairperson looked me in the eye and demanded that I fix certain students’ grades or possibly face severe consequences. He directed me to turn the failing grade of the student who wrote that email into an A. I was then told to turn the other complaining student’s grade into a B, but directed not to touch the failed grade of a third student who had not complained. I was to meet with the two students and allow them to invent some sort of extra credit assignment that would be the basis for these concocted grade changes. I refused to alter any of my grades, as there was no legitimate reason to do so. He informed me that students who pay a large amount of tuition are entitled to any grade they feel entitled to. I decided to consult with the faculty union to see if there was any way I could avoid compliance with the new chairperson’s demands. The union president told me that I should fix the grades, as that was a routine practice at this institute. Even though I was forced to comply with his demands, I made it clear (in writing) that it was the intent of these multiple administrators to fraudulently alter grades, and it was not my choice to do so.

The day after I submitted my grades for the subsequent courses I taught for the institute, the new chairperson sent me an email indicating that I was indefinitely removed from the institute’s list of available instructors and permanently blacklisted from the entire institution. His email specifically mentioned the controversy over the grade changes. I went to see the director of HR to try to get my job back. For over an hour, I discussed all the events that had transpired. The director sat there with a blank pad in front of him and wrote nary a word. When I asked him what would be done, he answered, “students who pay $45,000 for tuition can get whatever grade they ask for.” This was a reiteration of the same phrase used by both the new chairperson and the union president. The director of HR told me he would do nothing, turned his back on me, and walked away. Then, just 6 weeks after I was dispensed with, the chairperson decided to do the same to my kinsman who had worked there for nearly twenty years.

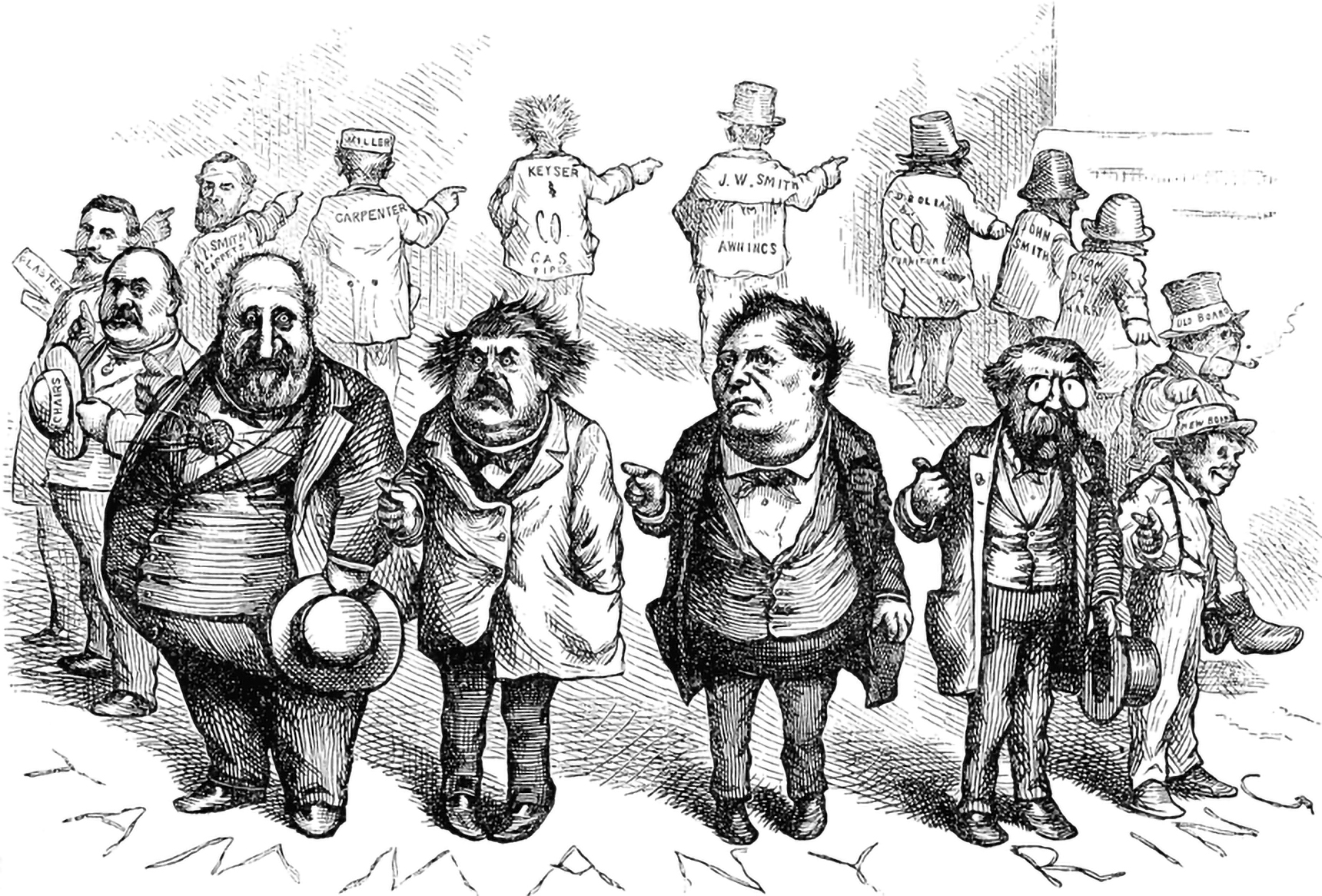

This whole experience has truly opened my eyes to the dreadful working conditions that part-time college faculty routinely face. At the institution described here, 85% of faculty members are part-timers. You know that working conditions are dire when both faculty union and human resources couldn’t care less (and admit to not caring less) about 85% of the faculty. The union’s contract extends dozens of articles covering protections to those 15% who need them the least. For those 85% of us who need them the most, there are virtually no protections. Like most private colleges, the union fights for their full-time employees, winning them large salaries. Part-time faculty are paid low wages, exploited by the colleges, and ignored by the union. I had over 80 students during my one year of teaching, which earned the institute nearly $250,000 in tuition for my courses alone (based on the dollars per credit formula). Full-time employees (some of whom taught fewer courses than I did) made upwards of $75,000 annually with benefits. Part-time faculty were paid $ 4,500 per course (with a 2 course per semester maximum) with no benefits. That is evidence of a massive pay disparity between two groups of people performing identical work. The salary gap could potentially be greater than that. This pay disparity is not limited to private institutions: it is a reality for all institutions of higher education nationwide. Structurally, it is reminiscent of medieval practices, wherein adjunct faculty fill the role of college serf in the name of preserving “quality higher education.”

But there is not necessarily quality in higher education, even (or perhaps especially) at private colleges with high tuition prices. Often the quality of education takes a back seat to the almighty dollar. Although we may be able to overlook a lack of income, institutions routinely do not. The awareness of institutional austerity is such a well-known fact of modern higher education that entitled students use that knowledge to exploit the flawed system. The first thing my student said to me after he failed the course was “I’m going to talk to the dean because I know he can do something about this.” He wasn’t wrong. In a good old-fashioned shake down, he threatened to “quit” the school and take his money with him unless he was satisfied. Adjuncts have no rights or protections, forcing an ethical dilemma: should we compromise our integrity, lower the quality of education, and keep our jobs? I would not and look where it got me.

The quality of education is no longer the primary concern of colleges. During my first semester, I received excellent feedback from my colleagues and original chairperson and exceptional student evaluations both semesters (even from those students who would fail the course). Two courses’ evaluations were so extraordinary that the new chairperson refused to let me see or keep them, as he knew I would be fired. Some of my colleagues, disgusted by his behavior, gave me access to the evaluations. Regardless of how effective we are as educators, the only metric to judge our efficacy seems to be in revenue. This emphasis on money was perceptible in the grade-fixing process: the biggest shake-down artist was to get an A; a nuisance to the administration was to get a B; and the third, non-complaining, student who failed the course was not to have her grade touched (thus forcing her to pay to retake the course). The administration seemed unconcerned that two students who earned an F wound up getting better grades than students who legitimately earned a B or C, not to mention those students who actually earned an A. In a perfect world, intellectual acuity and pedagogical efficacy would be the only metrics used to determine our strength as educators, but higher education (particularly private higher education) is anything but perfect.

Private colleges seem to go out of their way to create an imperfect model of higher education. When the president of the faculty union was informed of the institution’s determination to fire me, he chose to ignore my grievances rather than advocate for me. What sort of union works so overtly against its members’ interests? The head of advisement was partly responsible for convening two department heads and a dean to fabricate grades and falsify school records. According to the president of the union, one of the college’s deans was no stranger to coordinating multiple department heads to artificially improve students’ poor grades. When this corrupt brand of ad-hoc committee is created within a college, adjuncts are powerless to object. It is this model of imperfection that allows private colleges to thrive at the expense of adjuncts.

It is time to stop exploiting adjunct educators in institutions of higher learning. Instead of passively allowing this exploitation to continue just to increase institutional revenue, we must stand up and fight for the quality of higher education that all students so rightly deserve.