Zehra Husain

A political movement has been stirring in Pakistan. 26-year-old Manzoor Pashteen from South Waziristan, also called ‘Pakistani Che,’ leads the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM), which translates into English as the Pashtun Protection Movement. PTM held a political rally on 13 May in the country’s commercial hub, Karachi, with thousands of people in attendance. It took Pashteen almost a day and a half to reach the rally from Islamabad. He was first barred from boarding his flight from Islamabad to Karachi. He then tried his luck at the Lahore airport, where he was detained by security officials, only to be released once his flight had taken off. Driving his way to Karachi, he was stopped twice for questioning. When Pashteen finally reached the site of a dimly lit rally (government authorities had not given PTM organizers permission to light the entire venue) in the Pashtun-dominated outskirts of Karachi, he said to an emphatic crowd: “It took me 40 hours to get here, even if it took 40 years I would have still made it.”

A political movement has been stirring in Pakistan. 26-year-old Manzoor Pashteen from South Waziristan, also called ‘Pakistani Che,’ leads the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM), which translates into English as the Pashtun Protection Movement. PTM held a political rally on 13 May in the country’s commercial hub, Karachi, with thousands of people in attendance. It took Pashteen almost a day and a half to reach the rally from Islamabad. He was first barred from boarding his flight from Islamabad to Karachi. He then tried his luck at the Lahore airport, where he was detained by security officials, only to be released once his flight had taken off. Driving his way to Karachi, he was stopped twice for questioning. When Pashteen finally reached the site of a dimly lit rally (government authorities had not given PTM organizers permission to light the entire venue) in the Pashtun-dominated outskirts of Karachi, he said to an emphatic crowd: “It took me 40 hours to get here, even if it took 40 years I would have still made it.”

Bodies stopped from moving in space — bodies deemed so troublesome that state institutions manage their mobility by putting obstacles in their way — is one of the defining facets of racism. PTM stands against this institutional racism and routine harassment of tribespeople from what used to be known as Pakistan’s semi-autonomous Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA). Until this May, FATA was under the jurisdiction of the draconian Federal Crimes Regulation (FCR) law, which was introduced during British colonial rule. It has recently been merged with the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) province – a historic move on part of the soon to be departed present government.

The roots of state violence and harassment run deep in FATA’s history. In the 1920s and 30s, FATA was bombed by the British because the tribespeople rebelled against the colonizers. The militias that rose against the British were first empowered in the late 1800s to protect the borderlands from the threat of the Russian invasion. During the Cold War, militias in FATA were trained by US and Pakistani forces to fight the Soviets in Afghanistan. After 9/11 the tables turned yet again, and five military operations have since taken place in FATA. The latest of these was the Zarb-e-Azb, which displaced about 5 million tribespeople from the region, and the people of FATA have been the victims of U.S.’s unmanned drone wars for the last thirteen years. One of PTM’s demands was the mainstreaming of FATA into Pakistani politics, since people of the region have traditionally been seen as only half-citizens of the country and denied representation. More importantly, however, they ask for the recovery of ‘missing people’ who have been picked up by the state under suspicion of colluding with militant organizations. The PTM asks for repatriations and the formation of a truth and reconciliation commission.

But what sparked the PTM? The movement itself started after the extra-judicial killing of a 27-year-old Waziri man called Naqeebullah Mehsud, who was shot in a staged encounter by Karachi’s notorious police chief Rao Iftikhar. Fake encounters are commonplace in Karachi. They have employed to disproportionately target tribespeople from FATA and north of Pakistan, often migrants from working-class neighborhoods in the outskirts of the city fleeing military operations. Naqeeb was one of many who came to Karachi to find employment and support their families.

But what sparked the PTM? The movement itself started after the extra-judicial killing of a 27-year-old Waziri man called Naqeebullah Mehsud, who was shot in a staged encounter by Karachi’s notorious police chief Rao Iftikhar. Fake encounters are commonplace in Karachi. They have employed to disproportionately target tribespeople from FATA and north of Pakistan, often migrants from working-class neighborhoods in the outskirts of the city fleeing military operations. Naqeeb was one of many who came to Karachi to find employment and support their families.

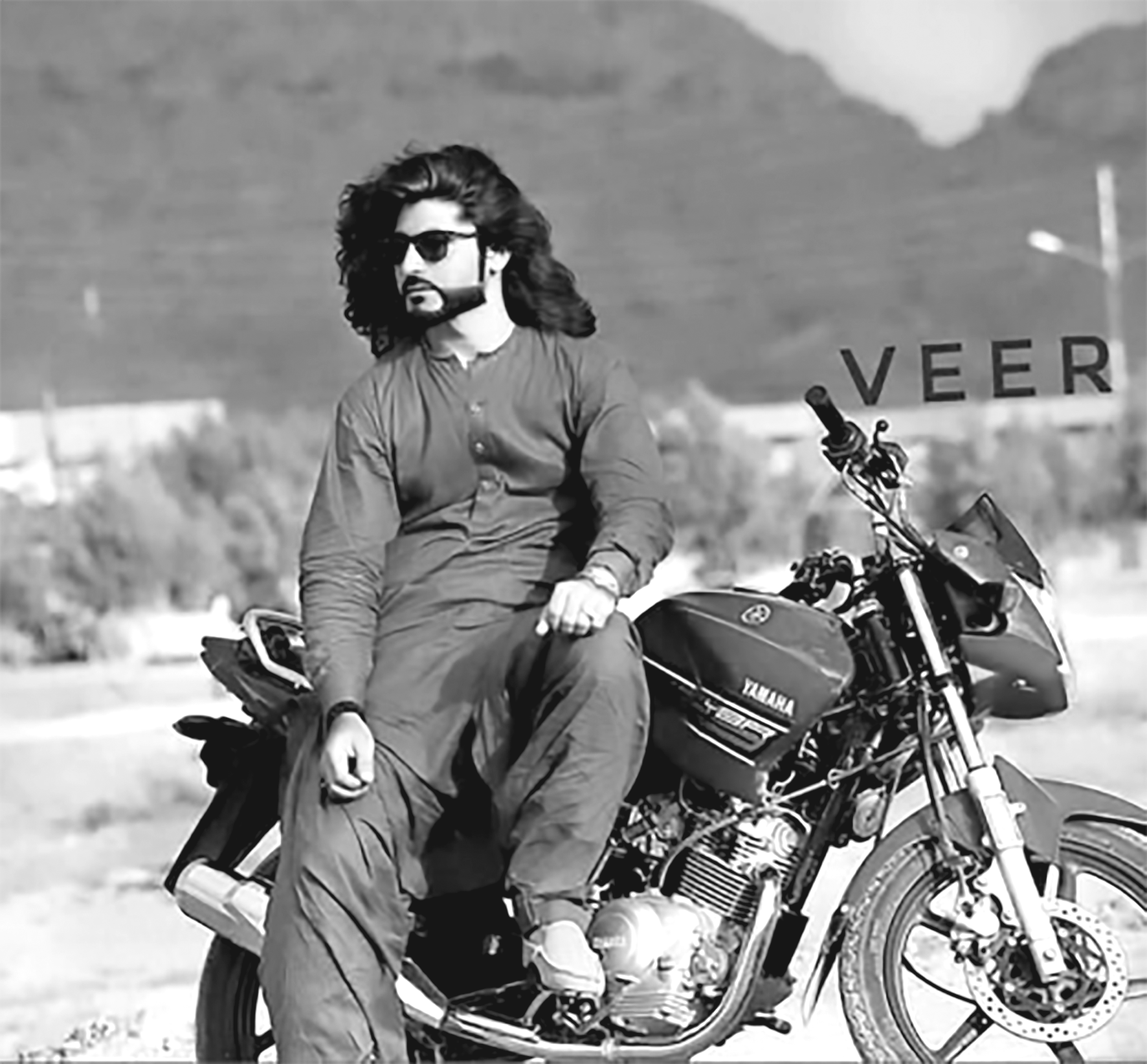

Authorities stated that Naqeeb was a member of the outlawed Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, a claim that has been denied by his family members. Mehsud and Waziri peoples from FATA routinely experience harassment and ethnic bias, because their last names are often taken to index terror links, and Naqeebullah Mehsud was an easy target for the police. Naqeeb’s murder caused an outcry on social media, where the news of the fake encounter circulated alongside Naqeeb’s images. Naqeeb’s photographs showed him in his full glory: sporting a sharp hair-do and wayfarers, holding a fancy smartphone. Some people insisted upon his innocence by saying that he was an aspiring model. Others said he was looking into establishing a business in Karachi in order to provide for his family. The circulation of Naqeeb’s images both on social media as well as in the mainstream media showed the kind of person that would could only be seen as the opposite of a terrorist.

Photographs are troubling objects. On the one hand, visual signs have historically been the most effective means of typifying people, especially criminals, by means of physiognomy and phenotype. On the other hand, photographs, especially portraits, grant dignity to their subjects. Allan Sekula famously defines this paradox of photography as its “repressive” and “honorific” function, respectively. In the case of Naqeeb’s murder, the police force had no visual signs to typify him as a criminal. His alleged terror links were based on his last name, the fact that he was a native of Makin, once a heartland of Taliban, and that he travelled between South Waziristan and Karachi. In the absence of visible signs, non-visual markers of lineage were used to typify him as a terrorist, eventually leading to his violent murder. It is no wonder then that this void was filled by the hypervisibility of Naqeeb’s images. “The photographs of a sharply dressed handsome aspiring young model,” wrote Pashteen in an op-ed for an English daily, became “a testament to his innocence”.

PTM crystallized as a concerted action partly because of the affective investments evoked by Naqeeb’s images. Moreover, the outcry against police chief Rao Iftikhar was so strong that he was stripped off his title and a case was lodged against him in the anti-terror courts. The potency of images, however, is not in any way limited to PTM. Over the years, there have been protests against military institutions in Pakistan for the disappearances of activists from Balochistan, Pakistan’s southwestern province, which has been demanding independence for two decades. In 2013, families of the missing Baloch embarked on a long march from Quetta to Islamabad, carrying ID photographs of their missing relatives and demanding a fair inquiry into the matter.

PTM crystallized as a concerted action partly because of the affective investments evoked by Naqeeb’s images. Moreover, the outcry against police chief Rao Iftikhar was so strong that he was stripped off his title and a case was lodged against him in the anti-terror courts. The potency of images, however, is not in any way limited to PTM. Over the years, there have been protests against military institutions in Pakistan for the disappearances of activists from Balochistan, Pakistan’s southwestern province, which has been demanding independence for two decades. In 2013, families of the missing Baloch embarked on a long march from Quetta to Islamabad, carrying ID photographs of their missing relatives and demanding a fair inquiry into the matter.

As material objects, ID photographs perform certain kinds of political work. As Elizabeth Edwards has noted, ID photographs are used ubiquitously in photo montages and albums. However, they are often remediated into serving different social and political uses: from memorializing the death of a loved one at funerals to carrying enlarged ID photographs to protest the disappearance of activists. Karen Strassler argues that as objects, ID photographs are unique in that they are ensnared within the gaze of the state. In their first instance, they form the system of documentation that renders bureaucracy and bureaucratic subjects legible. However, when repurposed in the form of enlarged portraits in political protests, these ID photographs are given a dual meaning. In their remediated forms, these images are haunted by the absence of individuals who were once given recognition by the state as its legal subjects and citizens. Now the images are used for making claims on the state to recover these missing peoples who have been illegally rendered neither dead nor alive.

Naqeeb’s images did similar kinds of political work: making claims on the state against its violent and corrupt policing of Waziris and Pashtuns. However, they were more potent as standing evidence to Naqeeb’s innocence, because they were a genre of images different from ID photographs. There was an excess of signs in Naqeeb’s images that humanized him – in ways that one could say mimed class mobility for an economic migrant rather than just being a testament to his citizenship. Sitting on a Yamaha motorcycle against the rugged landscape of mountains, wearing a teal shalwar kameez, the brown in his hair accentuated by photo re-edits, Naqeeb performs a masculinity that is the opposite of what urban Pakistanis confer to people from the ‘religiously orthodox’ tribal areas. Being photographed with commodities evokes a sense of class mobility in literal terms, but these aspirations get entangled with a religiosity acceptable and appealing to urban Pakistanis. In the image where he is photographed praying next to a motorcycle against a hilly landscape, he performs the trope of a good Muslim: someone who is grateful for their wealth. In other words, this photograph suggests that being religious and being upwardly mobile go hand in hand. One can then read these images as evidence to claims of his innocence raised by his relatives, who assert that he wanted to open a clothing business or that he was an aspiring model.

Most of Naqeeb’s images are inscribed with the name ‘Veer’. In fact, his Facebook page, where he posted most of these photographs was called ‘Apna Veer’ (Our own Veer). This was Naqeeb’s alias. Some also say it was his nickname. Naming is one of the devices through which identity is performed. Veer appears in the background of the photograph in the mountains. In the second image, it is written on the arm rest of a visibly torn car seat. The image is imposed on a background that stands in sharp contrast to the tattered seat. A large waxing moon-like object stands in the background of a bright blue sky, emitting cloudy white light which touches the white of Naqeeb’s clothes. This image evokes mobility in an almost supernatural way. Seen together, the use of the name Veer and the utility of this backdrop construct an endless medley of identities for Naqeeb. Veer transforms Naqeeb’s identity to a masculinity that is different from one attributed to tribespeople. The use of supernatural backgrounds transports him into an otherworldly place: a fantasy in comparison to the working-class neighborhood in Karachi and the war-ridden tribal areas. The image is almost comical in the hyper dreamscape it evokes. And yet the tattered chair on which Naqeeb is seated points to something very real: the poor conditions of photographic studios and their dilapidated props, which economic migrants, and other working-class peoples use in order to escape the drudgery of everyday life.

Most of Naqeeb’s images are inscribed with the name ‘Veer’. In fact, his Facebook page, where he posted most of these photographs was called ‘Apna Veer’ (Our own Veer). This was Naqeeb’s alias. Some also say it was his nickname. Naming is one of the devices through which identity is performed. Veer appears in the background of the photograph in the mountains. In the second image, it is written on the arm rest of a visibly torn car seat. The image is imposed on a background that stands in sharp contrast to the tattered seat. A large waxing moon-like object stands in the background of a bright blue sky, emitting cloudy white light which touches the white of Naqeeb’s clothes. This image evokes mobility in an almost supernatural way. Seen together, the use of the name Veer and the utility of this backdrop construct an endless medley of identities for Naqeeb. Veer transforms Naqeeb’s identity to a masculinity that is different from one attributed to tribespeople. The use of supernatural backgrounds transports him into an otherworldly place: a fantasy in comparison to the working-class neighborhood in Karachi and the war-ridden tribal areas. The image is almost comical in the hyper dreamscape it evokes. And yet the tattered chair on which Naqeeb is seated points to something very real: the poor conditions of photographic studios and their dilapidated props, which economic migrants, and other working-class peoples use in order to escape the drudgery of everyday life.

Walter Benjamin characterizes “commodities-on-display” for their representational value and not merely for the use or exchange value in the market; they enthrall crowds even when the objects involved are far from their reach. In her analysis of material culture of modernity, Karen Strassler builds on Benjamin’s formulation, adding that the use of these commodities – radios, cars, Vespas, airplanes – in studio portraiture transported the representational value of these objects into the home by capturing them in photographs. The use of cell phones, gold watches, motorcycles and wayfarer sunglasses in Naqeeb’s images also have representational value. They visualize a certain kind of subject – one that aspires class mobility and is also religious – that is the opposite of the racialized tribal subject. These commodities do keep crowds enthralled, but in ways that are political. In line with Benjamin’s insights about the democratizing effects of technology’s ability to infinitely reproduce images, Naqeeb’s photographs heighten the prospects of popular engagement. Circulating on multiple media platforms, these images meet urban Pakistanis half-way: on the screens of their phones via social media and news websites. It is then that these images can be remediated to argue upon his innocence, and spark an entire political protest in the form of PTM which questions the nature and value of freedom in Pakistan. Naqeeb’s murder is therefore a photographic event demonstrating the power and political potentials of images.