Rhone Fraser

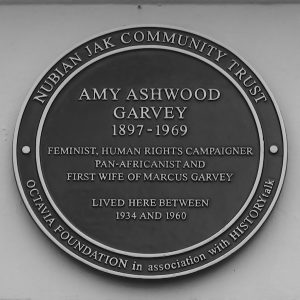

Amy Ashwood Garvey (1897-1969) was the first wife of radical journalist Marcus Garvey (1887-1940). In a year when numerous U.S. liberals are heavily invested in promoting the first U.S. female president, the life of a political leader like Amy Ashwood Garvey deserves recognition and study like never before. She was a leader who identified as a “feminist” like Hillary Clinton. In addition, she identified herself as a “Pan Africanist” and agreed with Garvey’s mission of “awakening the Negro to his sense of racial insecurity.” Ashwood sought to “awaken the Negro” through her strategic ownership of property; her promotion of the Negro World paper across Latin America and the Caribbean; her creation of a safe space for radical thought; her tracing of her Ashanti heritage from Jamaica to Ghana; her promotion of Garveyism in Africa where she sought to strengthen an independent Ghana as a symbol for African independence. Her life in the twentieth century stands as a valuable lesson for our own times on how to awaken all peoples of African descent to a world that continues to promote racial injustice and prevent the realization of any substantive form of Black nationalism. This essay will look at biographical works on Amy Ashwood Garvey and historical works that can throw light on her lived experience. Much of my engagement with these works stems from my research for a biographical play that I am working on. All of these works in some way speak to the central political project informing her life which is, in her own words, “the awakening of the Negro to his sense of racial insecurity.” This awakening comprehensively deconstructs the assumptions on which the current White supremacist capitalist economy depends.

Lionel Yard wrote a biography of Amy Ashwood Garvey in 1990, which was published by the Association for the Study of African American Life and Culture (ASALH). Then, in 2007, Tony Martin published another biography of her from his independent press, The Majority Press. While, Martin writes about the political history of Ashwood, Yard is more occupied with her emotional history in his book. “Awakening the Negro to his sense of racial insecurity” was Ashwood’s quote of Garvey, who approached her in Jamaica in July of 1914. His intellect appealed to her, as hers to him. According to Martin, Garvey invited Ashwood to join his then nascent Universal Negro Improvement Association (U.N.I.A.) after hearing her win a debate by arguing that “morality does not increase with the march of civilization.” She would see the truth of this argument in different forms as her twentieth century life progressed. Marcus began a very involved courtship with Amy Ashwood. Lionel Yard describes his steadfast determination to be by her side despite her mother disapproving of him. Ashwood’s mother was so staunchly opposed to their union that she sent her to live in Panama with her father, who was a positive affirming force in her life.

When young Amy Ashwood inquired about her African past, her father introduced her to her great grandmother Grannie Dabas, who would later facilitate Amy’s journey to Ghana in 1947 to meet the descendants of her great grandmother’s parents. Her father was also a successful baker who owned businesses in the Panama Canal Zone and in Colombia. Here, Olive Senior’s 2014 book, Dying to Better Themselves, proves to be an important start in understanding life in Panama from the perspectives of Panamanians, Jamaicans, and Barbadians who emigrated there for job opportunities. Senior gives a vivid account of the labor that went into building the Panama Canal while Ashwood lived there from 1916 to 1918. In addition, she also describes the strict color and class stratifications among the canal laborers that Marcus Garvey initially saw on his visit to Panama in 1911.

Douglas Egerton’s 2015 book, Borderland on the Isthmus, describes Panama Canal life but mainly from the perspective of the white, often U.S.-born citizens, known as “Zonians.” Stratifications on the Panama Canal included white Zonians at the top, who did not have to pay utilities and black laborers who did at the bottom. Julie Greene’s 2009 book, The Canal Builders: America’s Empire at the Panama Canal, describes only some of the numerous tensions between colors that Ashwood knew intimately during her time there. White Zonians were paid for their less menial labor in gold whereas black Panamanian, Jamaican, and Barbadian labor were paid in silver. Both Senior and Garvey describe life from the perspective of the laborer.

Tony Martin’s 1976 biography of Marcus Garvey called Race First mentions Garvey’s stint as a newspaper editor in Costa Rica, Honduras, and Panama before Ashwood went there. He writes that Garvey was a timekeeper for the United Fruit Company, where he organized Black laborers for a few months in order to “awaken” them to their exploitation by the Company. Aviva Chomsky’s 1995 book, West Indian Workers and the United Fruit Company, 1870-1940, is an account of the various attempts that went into destroying the printing press in Costa Rica that Garvey depended on.

Ashwood saw the same need to “awaken” the laborers of the Panama Canal who were locked within a strict color and class hierarchy. In Panama, she learnt the importance of property ownership from her father, and would later apply Garveyite principles upholding property ownership for the benefit of communities of color in nearly every place she lived in after Panama.

Martin writes that about a year and a half after arriving in New York and working with Garvey to build the membership of the U.N.I.A., Ashwood’s father gave her about one thousand dollars to buy a brownstone in Harlem, without the permission of Garvey. This, among other reasons, including charges of infidelity detailed in Martin’s biography, led Garvey to seek an annulment of their two-month old marriage on 6 March 1920. He sued Ashwood in August of that year on grounds of adultery. However, according to Yard, Garvey never legally divorced Ashwood because at the time of their marriage, as she wrote to Amy Jacques, there was no federal divorce law. Ashwood filed a countersuit against Garvey saying that his marriage to a second Amy, Amy Jacques, qualifies as bigamy. Yard also describes how, on several counts, Ashwood believed that Amy Jacques Garvey usurped her power and benefited from the hard work that she initiated with the U.N.I.A. in Jamaica and the United States. Ula Y. Taylor’s meticulous 2002 biography of Amy Jacques Garvey entitled The Veiled Garvey describes the important work Amy Jacques undertook to publish Garvey’s The Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey when he was imprisoned in 1923.

At the same time, Yard’s biography also states that it was Ashwood who introduced Amy Jacques to Garvey. In Taylor’s biography of Amy Jacques, she credits Ashwood for making sure that the U.N.I.A. constitution required that each new branch have not only a president but a female co-president. Ashwood encouraged Garvey to hire Amy Jacques as secretary. Jacques was also a bridesmaid at Ashwood’s 1919 wedding to Garvey, and Yard writes about Ashwood’s betrayal most comprehensively. He writes that Garvey secretly established residence in Missouri in order to deny Ashwood due process in his annulment. After Garvey married Jacques in 1922, Ashwood sued Garvey for “absolute divorce” and Yard writes that the legal battles between them ended in a draw. Despite this, she continued the pursuit of “awakening the Negro when she toured Europe and, after a worldwide distribution of the Negro World newspaper, identifies publicly as “Mrs. Amy Garvey.”

Around 1923, Ashwood meets legendary Calypsonian singer Sam Manning and begins a professional and romantic relationship with him as a pioneering musical theatre producer. She and Manning write and produce several plays described by both Yard and Martin. Sandra Pouchet Paquet’s edited 2007 collection of essays on Calypso, called Music, Memory, Resistance: Calypso and the Caribbean Literary Imagination, shows calypso as a critique or mocking of the colonial order that Manning’s music provided in a subtle way.

Robert A. Hill edited The Marcus Garvey Papers, which consists of nine volumes including key editorials of the Negro World newspaper and papers from Garvey’s most profitable business, Black Star Line enterprise, which was started months before he married Ashwood. Hill’s edited collection includes memos from the Bureau of Investigation, run by J. Edgar Hoover, surveilling the U.N.I.A. These memos show a narrative of a successful undermining of the Black Star Line with the help of informants who deceptively posed as U.N.I.A. members sympathetic to Garvey’s black nationalist cause. Hill’s early volumes also note the presence of Ashwood at U.N.I.A. meetings.

Jeffrey B. Perry’s edited collection called A Hubert Harrison Reader, includes the writings of Garvey’s newspaper editor and bibliophile Hubert Harrison, who says that the failure of the Black Star Line and the Garvey movement was not due to the trumped up charge by the government but was rather a result of Garvey trusting people who had little knowledge of ships or ship building. While Yard attributes the Garvey movement’s failure to Garvey’s mercurial temperament, Martin quotes Ashwood in a 1960 Ebony magazine interview with Lerone Bennett Jr., where she notes that Garvey’s failure was due to his inability to share responsibility and his being too autocratic. She also tells Bennett that as the black man attempts to erase the social impediments and psychic debilitation caused by centuries of brainwashing into the belief of a basic inferiority, he arises “confident, and determined the recapture his fundamental rights as a human being, the kind of man the black woman would gladly love, honor and respect.”

Ashwood’s interview anticipated two studies that her life and experience speak to. The first study her analysis anticipated was the growing white mainstream publishing industry’s exclusive interest in black women that sparked within a year of her passing, as seen in the 1970 publication of The Black Woman by Random House and edited by Toni Cade Bambara. The second study her analysis speaks to is the pioneering work by Black psychologists like Kobi K.K. Kambon on cultivating positive Black relationships. In Kambon’s self-published book, African/Black Psychology in the American Context: An African Centered Approach, he writes that African nationhood consciousness was destroyed by Eurocentric conceptual incarceration, and that men and women who are involved in functionally relevant Africentric (Kambon’s term for African centered) relationships must have a strong sense of their collective African identity and cultural heritage.

When Amy and Sam moved to London in 1936, they opened a night club and restaurant called the Florence Mills Restaurant and Social Club that, Yard says, provided tribal fellowship for black immigrants in England “who needed a shelter from the stress and strain of living in a foreign country.” This club was a testament to Ashwood’s determination to create a safe space for radical thinkers. Her Florence Mills club was a place where intellectuals like C.L.R. James organized meetings for the International African Friends Service of Abyssinia, in response, Martin writes, to the Italian fascist aggression against Ethiopia. It is likely that James worked on early drafts of his original 1938 history of the Haitian revolution called The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution in Ashwood’s club, fed by her nourishing meals, as she was also known to have been an impeccable cook.

Bryant Terry’s 2014 book called Afro-Vegan: Farm Fresh African, Caribbean, and Southern Flavors, Remix includes a recipe for a drink called the “Amy Ashwood” that contains ginger and cayenne. This book that James was writing while frequenting Ashwood’s club is notable for its exclusive lens that relates the struggle of the Haitian people against European propaganda to the Western propaganda against efforts at black self-determination in his own time. James writes about Toussaint L’Ouverture’s personal failures in a manner similar to how Ashwood characterized Garvey’s personal failures, as quoted in Martin. He had the space to offer a serious study of analyzing the Garvey movement in a way that would ultimately improve nationalist movements.

Hakim Adi’s 2015 book, Pan-Africanism and Communism, also looks closely at this decade and evaluates the working class movements among Black immigrants in London at this time. In London, Ashwood met J.B. Danquah, a London student from the Gold Coast, to whom she told of her Ashanti heritage, and Danquah helps her locate descendants of her ancestry. By 1947, Ashwood begins tracing her African heritage, anticipating by thirty years a practice made popular by Alex Haley in his television miniseries in 1977. Martin wrote a 1990 appendix where he retraces Amy Ashwood’s steps called “In the Footsteps of Amy Ashwood Garvey: To Kumasi and Darman in 1990.” He includes another appendix by Ashwood called “My Ashanti Roots” that details how her great grandmother was sold by the Ashanti to the English.

Ashwood’s friendship with J.B. Danquah continued up to and beyond Kwame Nkrumah’s role as leader of Ghana in its independence from Great Britain. However, Danquah challenged Nkrumah’s leadership on so many levels. Yard writes Amy Ashwood tried to get Danquah to meet with Nkrumah and reconcile their political differences, but to no avail. Danquah’s consistent critique against what he saw as Nkrumah’s capitulation to British imperialists landed him in prison, on Nkrumah’s orders, where he remained until he died. Ama Biney’s 2014 book, The Political And Social Thought of Kwame Nkrumah, candidly discusses Nkrumah’s missteps that allowed C.I.A. functionaries to succeed in deposing him in 1966. Kwame Botwe-Asamoah’s 2004 book, Kwame Nkrumah’s Politico-Cultural Thought and Politics, provides a more sympathetic look at Nkrumah and shows Danquah as a die-hard traditionalist who simply wanted to replace Nkrumah’s position of privilege with British imperialists.

A close study of Amy Ashwood Garvey’s life is provided by her own papers that includes her numerous unpublished manuscripts. Her unpublished manuscripts are currently in the Lionel Yard Collection which is in the possession of his family.

More important however is the anticolonial, Pan-African, anti-Zionist lens through which Martin looks at Amy Ashwood Garvey’s life. He is particularly sensitive to the ways that, following Garvey’s independent commercial success and divorce from Amy Ashwood, white, Jewish moneyed interests like Lew Leslie employed both Sam Manning and Amy Ashwood to be part of shows that used blackface and profited from stereotypical depictions of black people. Martin writes about how Judge Julian Mack, an avowed Zionist, sentenced Garvey to prison while supporting his rival group the N.A.A.C.P. A close look at Amy Ashwood Garvey’s life shows that twenty first century scholarly attention on Garvey is not only woefully late but woefully hypocritical, because it willfully ignores the latent influence of Marcus and Amy Ashwood Garvey throughout the twentieth century.

Comments by Advocate