By: David Firester

The Global Terrorism Database (GTD), which is managed by the University of Maryland’s federally funded National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) recently released its 2015 user-friendly database to the public. The significance of such a robust catalogue of terrorism is that has been used to generate scholarly articles, which provide evidence to buttress official reports, thus leading decision makers to contemplate policy options. It is therefore very important to understand the degree of accuracy associated with the GTD’s statistics, as well as the attendant policy implications that might be drawn from them. Although I have criticized the database elsewhere, here I am primarily concerned with the inferences that might be mistakenly arrived at with regard to the situation in Israel. I have found a few trends, some factual errors and some palpable bias, which I will highlight and analyze below. My aim here is to demonstrate how a flawed database may distort the facts that can influence future policy decisions.

Jews Behaving Badly: Misrepresenting (and Fabricating) Facts

A micro-level review of the alleged Jewish terrorism reveals a few serious anomalies. After a careful review of the database, I have discovered that several of these alleged events either didn’t transpire, or their occurrence was doubtful (see Table 1). Either a source claimed by the GTD didn’t exist, was recycled from a previous year, or was suspicious in nature. The last category either relied on single, uncorroborated Arab sources, or had failed to mention that a matter was investigated by the police and deemed not to be a terrorist attack.

Table 1: Poor Data on Jewish Terror Attacks in 2015

| Didn’t Occur | Doubt Occurred | Misrepresented Facts |

| 201502030107 | 201510030023 | 201510130063 |

| 201502250058 | ||

| 201502250059 |

In trying to uncover facts about an event, it became apparent that a coding bias exists. An Arab terrorist attack in East Talpiot/Armon HaNatziv, a Jewish neighborhood, was mistakenly coded in the “West Bank and Gaza Strip” dataset. The database specifically names the intersection of Olei HaGardom St. and Moshe Barazam Street [sic; Barzani] as the attack location. Although the attack did take place on the former street, there is no indication that it did so at the intersection of the latter. This matters because if the attack were to have taken place where the GTD says it did, then it would support a narrative that the lethal attack on Israelis (including an American citizen) occurred in the so-called “occupied territories,” thus lending credence to the oft-cited attack rationale associated with “resistance to the occupation.” Indeed, the GTD gives the coordinates 31.749712/ 35.236954, which is a Jewish neighborhood in Eastern Jerusalem. This seemingly minor detail informs the analyst as to where the GTD has decided to draw its own lines.

With regard to the “West Bank and Gaza” dataset, a closer look at the alleged attacks by Jews/Israelis, reveals some more strange coding preferences. For instance, on October 9 in Kiryat Arba, an event (201510130063; see Table 1) occurred, for which the perpetrating party was coded as “Israeli Settler.” According to the database, the incident resulted in no injuries and no weapons were used. The single source derived from a Palestinian news agency, Ma’an, which produced pictures, which failed to indicate an explicit act of violence. Rather, while carefully reviewing the photographic “evidence,” it appears that the Palestinian journalists were being forced to lower their cameras. Why? They entered a Jewish neighborhood to report on a recent local incident, in which a Palestinian dressed as a journalist stabbed an Israeli soldier. Occurring during the most violent month, October, and given the above-described specific circumstances was likely a defensive measure, rather than an act of “terrorism” that the database ascribes to “Israeli Settler[s].” Although there is room in the database to indicate doubt regarding the label “terrorism,” none was conveyed for the instant case.

For two “terrorism” incidents (201502250058/201502250059; see Table 1), which involved the alleged firing of automatic weapons at Palestinian homes, the GTD again used a single, uncorroborated, source. Judging from the language used in the article, there is reason to believe that it may not have occurred. One would think the GTD staff could have indicated doubt about its occurrence, but the database doesn’t accommodate such assessments.

While investigating a vandalism attack (201503040051), which likely did occur and was categorized by Israeli authorities as “Jewish terror,” according to one of the two sources the GTD used, an event (201411120036) from the previous year was mentioned. In that event, it was alleged by local Palestinians that a mosque in Mughayir was set ablaze by Jews. As the article points out, however, the police determined that the cause of that fire was faulty wiring. To their credit, the GTD did express doubt that it was terrorism, although it wasn’t removed from the 2014 database. Hence, deficient Arab engineering is given the equivalent status of an act of Jewish terrorism in the database. A similar incident occurred in 2015 (201508240041), along with a similar misdirected aggregate outcome.

Israeli Accountability for ‘Jewish Terrorism’

For all of the purported Israeli attacks inside Israel (excluding the West Bank and Gaza), only 1 (5%) resulted in the death of a (non-Arab) civilian, whereas the total number of non-perpetrator deaths in Israel for 2015 was 20. In this rare instance, the only one in which the GTD labeled the lone assailant as “Jewish Extremists” [sic], the perpetrator attacked a Gay Pride parade, for which he received a life sentence in prison. Israeli tolerance of others’ identities is supported by the fact that it is by far the only gay-friendly country in the region (to include Arab-controlled territory in the West Bank and Gaza).

With regard to attacks by Jews/Israelis in the West Bank (recalling that Gaza had none), only 1 of the 19 was lethal, but it resulted in 3 deaths, accounting for about 2.5% of all deaths caused by terrorism in this particularly named area. It was the July 31 arson attack against a Palestinian home, for which a man and a minor were originally indicted, although it remains unclear if the man had acted alone. Nonetheless, Israeli authorities have been actively pursuing the suspect’s potential ring of similar offenders. Again, we have prima facie evidence that the Israeli government takes Jewish violence seriously. The same can hardly be said about the Arabs.

Context

Providing a context for the database requires a keen eye for detail. To illustrate this, an attack was alleged to have occurred in Netanya (201510090056) in October, in which the GTD cites “sources attributed the attack to Israeli extremists.” Again, there was an uncorroborated single source, which, when checked, referenced a different article in which the account (in Hebrew) described a back and forth exchange between Jews and Arabs, the latter of whom were reportedly shouting, “Allahu Akbar.” In the week leading up to this event, 15 Arab terrorist attacks had already occurred inside Israel and the “West Bank and Gaza.”

As is summarized in Appendix A, the GTD indicates that there were 58 incidents of terrorism in the 2015 “Israel” dataset. Of that number, 8 were attributed to “Israeli Extremists” (7), or “Jewish Extremists” (1). The separate “West Bank and Gaza” dataset recorded 247 total attacks in 2015, with 5 attacks coded as “Israeli Extremists” (always plural) and 14 as “Israeli Settler”[1] (always singular), or just under 8% being attributed to Jews/Israelis. All 32 attacks in Gaza, exclusively featured Arab attackers and/or Arab victims and resulted in no fatalities.

In October alone, 45% (26/58) of the attacks in the “Israel” dataset occurred, 5 of which were coded as Israeli/Jewish. This translates to 19% of the monthly “Israel” total, or 63% of the 8 annual total. Similarly, the “West Bank and Gaza” dataset for October featured 72 attacks, or 29% of the total number of attacks in the West Bank and Gaza. For a comparative assessment, the previous 7 months featured a total of 74 attacks. The proportion of attacks by “Israeli Extremists,” or “Israeli Settlers,” when compared to attacks by others in that month was 6 out of 72, or 8%.

Combining the two datasets (see Appendix A), the data shows that of the total 305 terrorist attacks the GTD recorded for 2015, 27 (9%) were committed by Jews/Israelis, which if adjusted for the aforementioned fact that at least one attack didn’t occur and several others could not be substantiated would reduce the percentage to something around 8%. Privileging the raw figures provided by the GTD, during the month of October, the total ratio of Jewish attacks to that of the Arabs was 11:98, or 11%.

Analysts may be inclined to explore two distinct causal factors to explain the October violence. First, any actions of the Israeli military should be considered. Such actions do not meet the GTD’s definition of terrorism and would therefore not appear in the database. Secondly, any widespread Palestinian media campaigns that aimed to incite violence, which the GTD also doesn’t include, should be investigated. A single Israeli military action, or Palestinian broadcast, would likely not account for the level of violence that persisted at a high tempo beyond the month of October. Therefore, one should gauge their search results with an eye toward intensity, duration and chronological sequencing.

Conclusion: Trends, Deficiencies and Implications

The complete picture of the data can be found in Appendix A (below). To summarize, Jewish terrorism during 2015 represented approximately 10% of the total monthly attacks for the year, with 4 months having no attacks. Even in the most violent month, October, the monthly percentage of Jewish attacks never exceeded 11%. The overall statement about non-Jewish terror is that it was quite the opposite. The average monthly attacks were 90% and there were no months in which non-Jewish (read: Arab) attacks numbered less than 5. There were some months, however, when Jewish attacks were 0 and the non-Jewish attacks were exceedingly numerous.

In light of these statistics, one of the trends that appear to have causal relevance is that the Palestinian attack intensity increased in October, with no apparent connection to any Israeli attacks having occurred the previous month. Another trend appears to be that once Israeli terrorism was at its peak in October, it quickly diminished to 1/month for the next two months. This was despite the third apparent trend, which was that Arab terrorism ratcheted up quickly, but down slowly (and painfully).

Although the GTD does capture a fair number of incidents, its database is largely populated by students, who respond to directions provided to them by algorithms. The result is that one who is unaware of the context of particular conflicts, as well as some of the nuances that attend it, may inadvertently inflate ‘Jewish terrorism’ statistics. In contrast, the Israeli Security Agency (Shabak) composes its own, publicly available, annual reports on terrorism. Its 2015 report reflects statistics that differ markedly from those of the GTD database, but more scholars and policy analysts appear inclined to use the latter, rather than the former.

The reasons that the GTD’s aggregate data differs from that of the Shabak’s are threefold. First, there is a difference in the way attacks are calculated. The GTD doesn’t include many of the failed or foiled attacks, nor does it log most airborne projectiles originating in Gaza. This is a bit odd, considering that the GTD’s “Data Collection Methodology” includes “an intentional act of violence, or threat of violence by a non-state actor” [emphasis in the original]. One might be inclined to assume that the GTD considers Hamas to be a state actor. However, this would be out of step with the fact that they did record a Hamas assassination attempt within Gaza (201502160091) in 2015. Additionally, the GTD recorded (in the Israel dataset) only one rocket fired from Gaza (201510100023), but indicated that the assailants were “unknown,” therefore not coding them as “Palestinian Extremists.” To wit, there are only Palestinians living in Gaza and the act of firing on a civilian population is patently extreme.

The other requirements that the data must meet also render the exclusion of Hamas/Gaza as suspicious. According to the GTD’s methodology, a terrorist entity must meet two of three criteria, each of which describes Hamas and its activities. On cannot reasonably argue otherwise, unless the data coders are in agreement that such actions are somehow legitimate. This would place the GTD firmly in the camp of those who assert the rights of Hamas/Gazans to attack Israel. Such an inference, if it were correct, would undermine the credibility of START as a nonpartisan think tank. After all, the center is a “Department of Homeland Security Center of Excellence.”

The second reason that the GTD’s data differs from that of the Shabak’s has to do with the way in which it distinguishes territorial lines. As was already mentioned, the GTD has two distinct datasets for “Israel” and the “West Bank and Gaza.” Scholars who miss this fact will arrive at some very skewed conclusions. Even when accounting for this fact, however, the statistics are still vastly different.

Thirdly, the GTD doesn’t appear to retrospectively analyze the data it collects, although its leading scholars use the data to produce peer-reviewed journal articles and books. Again, I have listed a few occasions in which a matter was either reported to be a terrorist incident when it turns out not to have been, or an incident was said to have taken place when it seems likely that it did not. The unfortunate consequence is that the GTD’s aggregate data enables those who conduct macro-level studies to manipulate it in such a way as to draw imprecise conclusions. This is why I have offered a micro-level assessment of the GTD’s database with regard to a specific independent variable, Israeli/Jewish terrorism.

Bio

David Firester is the founder and CEO of TRAC Intelligence (Threat, Reporting, and Analysis Consultants), which is a premier threat analysis firm. TRAC Intelligence provides threat assessment in the private sector.

Appendix A: Visual Data

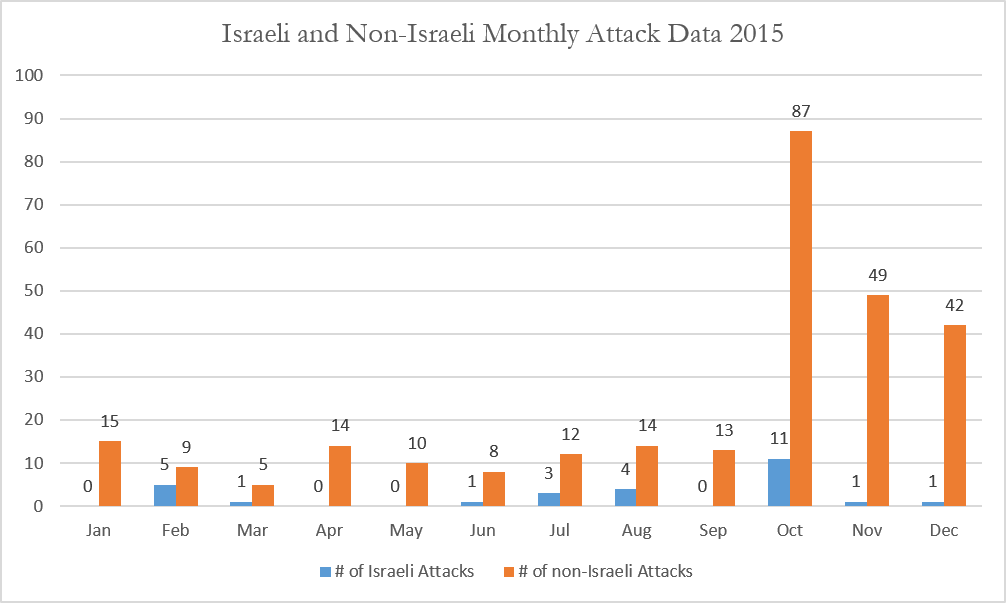

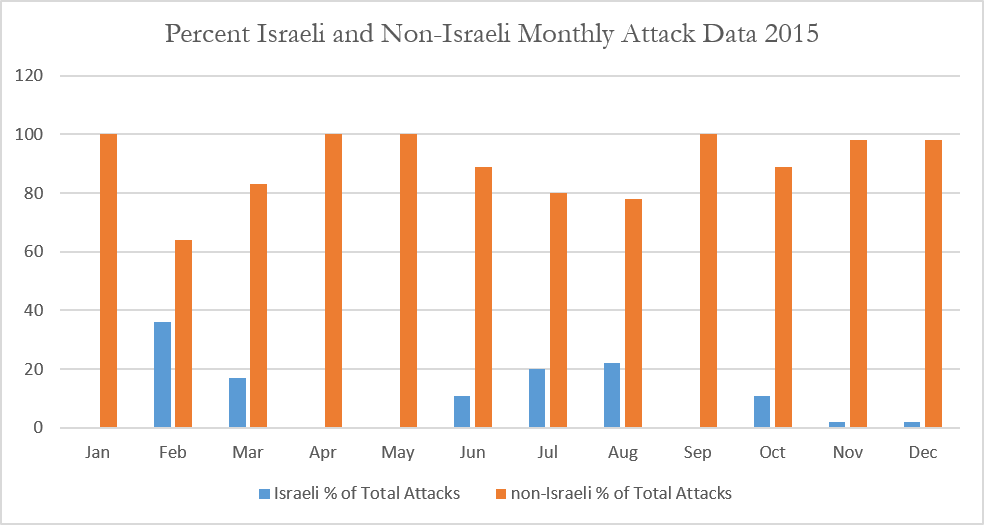

Despite the various faults with the data, identified above, the following is a visual summary of the GTD’s combined datasets, “Israel” and the “West Bank and Gaza.”

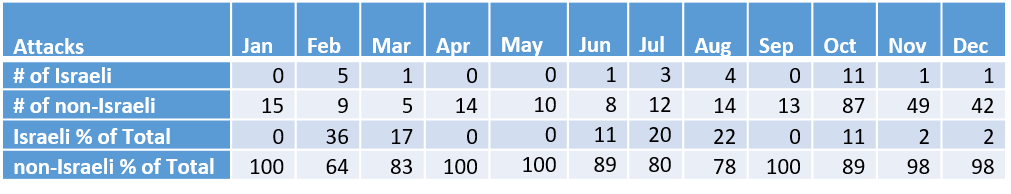

Table 2: Average Monthly Attacks in “Israel” and the “West Bank and Gaza” 2015

Source: GTD 2015 Dataset for “Israel” and the “West Bank”

Graph 1: Numerical Expression of Average Monthly Attacks in “Israel” and the “West Bank and Gaza”

Graph 2: Percentage Expression of Average Monthly Attacks in “Israel” and the “West Bank and Gaza”

[1] Such a distinction may be arbitrary, but calling someone a “settler” undermines thelegitimacy of their legal status as a citizen. In this respect, the GTD’s staff exhibits a clear bias.

Comments by davidfirester