This post is part of a series about my Portrait of a Collecting Strength project.

The data for my Portrait of a Collecting Strength project comes from a selection of African American collections at the Rose Library. To contextualize this data, I have been researching histories of African American collections generally, and at Emory in particular.

Emory made a significant commitment to its African American collections in the late 1990s, when Special Collections hired a curator for the collecting area. Emory, a historically white institution with a major endowment, has since become a major player in African American archival collections. In an effort to appreciate the institutional, cultural, and economic factors that led to this development at Emory and its impact on the national landscape of African American archives, I have been researching earlier histories of collecting.

** I’m grateful for Laura Helton‘s reading recommendations on this topic (and very much look forward to reading the book she’s working on, Collecting and Collectivity: Black Archival Publics, 1900-1950). **

Collectors and bibliophiles

The bibliographer and librarian Dorothy Porter (a major player in the building of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University) traces a line from the nineteenth-century African American private lending libraries and publishing houses to the twentieth-century major research institutions’ African American manuscript and rare book collections, which built on bibliophiles’ private collections. Porter’s “Documentation on the Afro-American: Familiar and Less Familiar Sources” describes the black bibliographic scene in the 1800s:

Since Negroes could not enjoy the same privileges as whites in libraries, they established for themselves some 45 literary societies between 1828 and 1846 in several large cities, mainly in the East, most of which maintained reading rooms and circulating libraries.

The history of segregation, the undervaluing of African American culture and history, and the underfunding of black institutions historically impacted and have continued to shape African American archives.

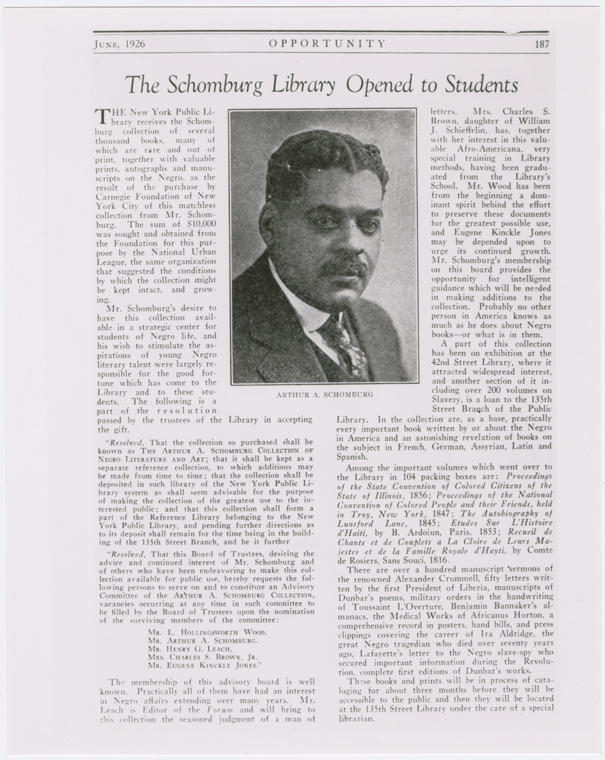

In 1912, Arturo Schomburg wrote to fellow collector John Cromwell. His letter anticipates the interest of collecting institutions in African American history. He also comments on the fact that it is whites who possess and have access to histories of the African diaspora (citing race theorist Blumenbach as the precursor), rather than the communities that produced that work. Dorothy Porter quotes Schomburg’s letter in “Bibliography and Research in Afro-American Scholarship,” in the Journal of Academic Librarianship (1976):

“It is the whites,” he wrote, “who have splendid libraries with many books by Negroes, they imitate Blumenbach who over 150 years before enjoyed the reputation of having a library by Negro authors.” He further wrote: “Patience is needed. I have devoted three years to collecting the silhouette of Benjamin Banneker…no great house devotes its time to Negro literature or books. It is a forgotten field, but as interest awakens the public mind will compel the libraries to have rooms devoted solely to Negro themes.

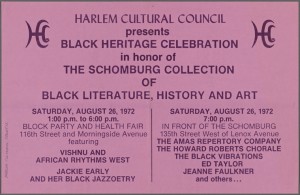

Indeed, later in the twentieth century many rooms and stacks and archival boxes in libraries were devoted to “Negro themes.” The awakened interest of institutions in African American history was in no small way shaped by Arturo Schomburg himself, whose collections formed the basis of the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Library (now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture).

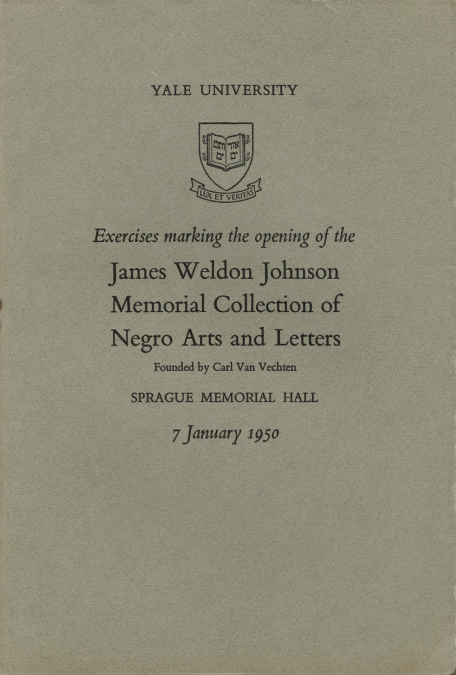

The role of individual collectors animates much of the history I have been reading. Carl Van Vechten’s role in building the Beinecke’s James Weldon Johnson Collection is widely known. Van Vechten also gave collections to the New York Public Library, Fisk University, Museum of Modern Art, Howard University, and more. (Kristen MacLeod’s “The ‘Librarian’s Dream-Prince’: Carl Van Vechten and America’s Modernist Cultural Archives Industry” in Libraries and the Cultural Record 46.4 provides an extensive account of Van Vechten’s contributions.)

Harold Jackman’s role in the shaping of the JWJ Collection at the Beinecke is less known, and less documented. Jacqueline Jones’ article in the Langston Hughes Review, “The Unknown Patron: Harold Jackman and the Harlem Renaissance Archives” (2004) begins to correct that. Jones argues, “It was actually Harold Jackman, perhaps a man too humble for his own good, who succeeded in obtaining much of the initial holdings of the collection” (60). Jackman also contributed to the Countee Cullen-Harold Jackman Memorial Collection at Clark Atlanta University.

Interpersonal Connections in Collections

Individual donors and librarians play hugely important roles in shaping the collections and archival holdings of institutions. (Those holdings, in turn, impact the stories scholars can tell about history and culture.) These interpersonal histories, however, are often not recorded, neither in the metadata apparatus presented in archives (in finding aids or collection descriptions), nor in written scholarly or narrative accounts.

While she was a graduate student in English at Emory, Amy Hildreth Chen (currently Special Collections Instruction Librarian at University of Iowa) wrote about the importance of interpersonal relationships to the archives in her dissertation. One dissertation chapter focuses on the relationship between poets Lucille Clifton and Kevin Young, who in addition to being an acclaimed poet, is a curator at Emory’s Rose Library. Chen discusses how the relationship they had preceding the placement of Clifton’s papers impacted her decision:

Young and Clifton demonstrate that relationships made outside the archive shape the development of the archive as an institution. Without Young as a curator, the Manuscript, Archive, and Rare Book Library would have had a more difficult time attracting Clifton to lodge her papers at Emory University. Researchers who use Clifton’s papers without realizing the circumstances which caused them to be housed at MARBL – in a city and state Clifton never lived in, at a university she where she neither attended nor taught – miss the significance of the untold “inner history” behind how these materials became available.

(Amy tells me a revised version of this chapter will be published in Collections: A Journal for Museum and Archives Professionals this summer.)

I am also very interested in this “untold ‘inner history'” of archival holdings. As I explore interconnections among the Rose Library’s twentieth century African American literary and artistic holdings, I am supplementing analysis data from the finding aids with interviews with curators and archivists to record the pre-histories of these collections’ presence at Emory.

Libbie Rifkin’s “Association/Value: Creative Collaborations in the Library” (published in 2001 in RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage) describes how the placement of papers in archives contributes to the cultural value and afterlife of poetic communities (for instance, her first example is Ted Berrigan’s literary magazine C in Syracuse’s poetry collections). Rifkin suggests ways that “collecting decisions–collaborations between curators, writers, and the fields they represent–in fact make literary history” (135).

As we undertake work on African American literary and cultural histories, we ought to pay critical attention to these collecting decisions and the institutions where they take place. I’ve recorded here a few examples of exemplary individuals, forgotten players, and interpersonal relationships that play a role in what gets collected where.

Comments by Anne Donlon