The television schedule is a complex concept; it is constantly in flux and subject to change, yet its rigidly based on historic structures that reflect the needs and requirements of the various structural institutions responsible for its creation and success. Its inherent fragmentation–the programs, the genres of programming, the advertising breaks, etc.–must come with its own carefully calculated logic, a logic made up of editorial, commercial, and professional choices that work together to create the perception of a unified self, of a consistent identity, a marketable brand/look. [1] (Barra)

I’ve been doing a lot of thinking about the unified image of the television schedule and the spectator’s experience of this fragmented totality. If I think about it in relation to the experience of binge-watching I just keep coming back to Lacan and the mirror-stage. The formation of the I, for Lacan, has to do with the child’s identification with her image in the mirror. This mirror image, however, while initially met with “jubilation” inevitably results in angst and longing. The desire for wholeness, for the potential within that unified image, causes agitation because the infant realizes that her state is one of lack, of fragmentation. The Ideal-I seen in the mirror gives the individual something to strive for, but in doing so also creates a disparity between the perfect image and the actual self; no matter how the individual matures she will never attain the reality of the perfected image. Upon its introduction to the outside world, this self-image must be defended because “it threatens to expose the fact that the self is an illusion done with mirrors” (Gallop 83).

Through this Lacanian lens, it would seem as though the televisual construct that we experience when we watch the small screen is a reflection/reiteration of our own experience of self-becoming. It becomes the embodiment of the fragmentations, the blips, the lacks within our physical selves, while giving off the perception of a seamless, fluid, complete entity (we all want to believe this, just look at Raymond Williams!).

But if you think about it, if we and television really really want to become that Ideal-I, we’re going to have to step up our game.

[Enter Binge Watching Stage Left]

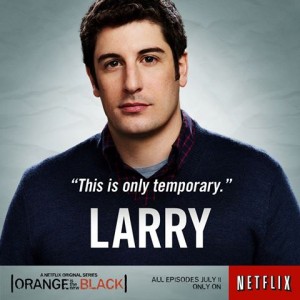

Binge watching–the continual viewing of episode after episode of the same show–via VOD, Netflix, Amazon, Hulu, etc.–in terms of our experience of it, seems to better mask this fragmentation; we can avoid commercial breaks, genre changes, the week of anticipation between one show and the next, and create the illusion of a seamless experience. These viewing platforms themselves mask the structures and fragments at place in creating their choice offerings, and work toward creating the fluid, unified experience you long for by allowing and encouraging the “automatic play next.” What I am saying is that just as these platforms better hide the fragmentation of their “choice offerings” (no longer “schedules”), and the financial, political, and commercial elements at play in these decisions, they also give us the same sensation of being more in control, more unified, as the continuous flow of one episode into the next creates a seamless fluidity of desire/gratification/identification. [2]

Elizabeth Wright has argued that “As a child is lured by its mirror-image […], which seems to promise a completeness it does not have, so the reader is lured by the text through the force of its representation” (620). This would make television the text we are lured by, the fluid unified whole that we desire for ourselves. So is television our ultimate “imago” or are we, as creators and consumers (ingestors) of television, as I have argued in this post, creating reflections and iterations of our own experience in the social/Symbolic realm?

1. “Brand Identity” is an expression that has been gaining popularity as television and magazines are constantly referencing people “keeping it on brand” i.e. “that jumpsuit is on brand!”

2. This binge watching shift finds its forefathers in the combination of the solitude of the multi-television set household, and the control of the ultimate phallic forefather, the remote control.

Bibliography

Barra, Luca. Palinsesto, Storia e tecnica della programmazione televisiva. Roma-Bari: Gius, Laterza & Figli, 2015.

Gallop, Jane. Reading Lacan. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1985.

Lacan, Jacques. “The Mirror Stage as Formative of the Function of the I as Revealed in Psycho analytic Experience.” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. Ed. Vincent B. Leitch. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001. 1285-1290.

Lorraine, Tamsin E. Gender, Identity, and the Production of Meaning. Boulder: Westview Press Inc., 1990.

Wright, Elizabeth. “Another Look at Lacan and Literary Criticism.” New Literary History. Vol 19 No 3, Spring 1998: 617-627. Jstor.

teronormative. Perhaps the brother, perhaps the child-like, resisting, straight man who lashes out against maturity, against identification, against empathy, perhaps he remains the symbol of straight whiteness, of safety in identification. But this, quite frankly, seems like a stretch, like a nod to the id.

teronormative. Perhaps the brother, perhaps the child-like, resisting, straight man who lashes out against maturity, against identification, against empathy, perhaps he remains the symbol of straight whiteness, of safety in identification. But this, quite frankly, seems like a stretch, like a nod to the id.