Who is the Audience? was written for a Baruch blog called Cacophony. I think I have a pretty good sense of who my audience is here – (Mom!) – just kidding – but also not. Along with a handful of friends, my family and a bunch of webbots – I like to imagine some people interested in writing or APA style or whatever political issue stumble upon this page occasionally. Anyway below is the post – and feel free to respond on the audience tip!

Earlier this semester a friend confided in me that he was having trouble writing, and I callously guffawed, “It’s just a blog post”. How those words haunt me now. I have experienced an inordinate amount of consternation, conflict and ultimately exasperation in my previous three attempts to compose this post. Each time I wrote about a page, and then decided that I couldn’t, wouldn’t or shouldn’t publish it on Cacophony. I felt like I was sinking into intellectual quicksand, the more I struggled, the deeper I sunk into a certainty that the writing I had spent an embarrassing amount of time on – literally hours – was for naught. As I sank lower and lower into the mire I began to ponder the thoughts and emotions that I felt were stopping me from blogging. I had set out to write a quick post about my research on blogging and I felt as thought the very concepts that inspired me to conduct my research were the same forces that were making it difficult to write about this research. Who was my audience? Ironically, it seemed I couldn’t blog about my dissertation on blogging. In brief, my research is about how the medium in which students compose expressive writing – on a blog as compared to in MS Word – interacts with their cognitive and emotional processes and the way they write, and I am subsequently exploring how these differences can be measured and ultimately I’m making an argument for why these differences matter. But back to my struggles.

First I attempted to write about my preliminary results.

What I’m noticing is that over time the participants are using more evaluative language – meaning they were investing more meaning and effort into their work. I closed my eyes and took a deep breath poised to compose the next sentence. All of a sudden I was in front of my dissertation committee, a stern silverback professor hand on chin in the thinker pose questioned, “But in that blog post you wrote, you stated that evaluative devices would increase and now it seems that is not the case. Can you explain this?”

I woke sweat drenched in a dark room, a red streak where my face had pressed against the keyboard. No, no, I decided I certainly couldn’t blog about my preliminary results.

Well, I thought, what if I write about my coding schema.

That seemed like a safe idea. I’d even begun describing it in cursory terms in my never to be published preliminary results. I again began banging away at the keyboard, this time describing the syntagmatic narrative-coding schema. But how could I describe this coding schema in a way that seemed relevant and meaningful to an audience not from my mini-niche discipline? How could I convince readers that the system I had spent hours fine-tuning with my adviser and research assistants was meaningful and worthwhile? Should I cite numerous theoretical and research articles in my blog post? If so, should I use APA, MLA or Chicago style and if Chicago would this be Chicago I or II? Even these questions seemed like they would bore readers to sleep. Furthermore, wouldn’t readers want to know at least what my preliminary results of this schema were? And I was still collecting data – what if some of my participants happened upon this post and then changed the way they were writing? No, oh no, I thought, this post on my coding schema would not do. Let me try something new.

Finally, I thought let me describe my methods.

Ah yes, I can just use some of what I’ve already written in my proposal and this will come easily. But of course it didn’t. The excerpts from my proposal were too dense and psychology specific. I decided to rewrite the methods with more accessible language. When I was nearly finished I realized what I had written was in fact better than my proposal and therefore could serve well as at least part of the method section for my final dissertation draft. And if I wanted to use it for my dissertation draft or perhaps for future publications than I had best not web-publish it. Why not a reader might wonder? As a psychology PhD candidate I’ve though a lot about whether to digitally publish my dissertation. What’s pushed me towards a traditional paper dissertation is the American Psychological Association guidelines, and subsequently any APA journals, that state a manuscript should not be more than 30% similar to work that is previously published. Without getting too far into the gritty details if I blogged my methods section it would make it difficult to use similar wording for future publications.

I’ve used this post to work through and make sense of my thoughts and emotions.

After writing about these fits and starts my audiences seem much less intimidating than when they were bottled up in my mind. In truth, unless I send them the link I don’t think my professors nor my participants will read this piece – and even then… Nor is it likely that whatever I wrote about my coding schema or methods would be identical to what I will write for future journal articles. One question is – does it matter that in “real life” these scenarios were unrealistic? In real life, I was wrestling with these thoughts and they were enough stop me from being able to or at least made me feel as though I couldn’t blog – which is sort of the same thing in the end. The power of these imagined audiences was literally paralyzing. Perhaps too, I was struggling to write about my dissertation because this work is so important to me, and I have yet to figure out how to distill the main points into a concise and accessible blog post. The struggle described in this post has likely moved me closer to being able to do just that.

There is also something very real about imagined audiences. And the commonality between my three false starts was my struggles with these audiences and the very real – though perhaps difficult to exactly define – audience of Cacophony readers. I was struggling to imagine Cacophony’s audience and therefore I was having trouble framing my argument in concise and accessible language. And what do those words really mean? Concise and accessible to whom? Business faculty, communications specialists (I’m not even sure what that means), psychologists, educators, linguists? I should admit I’m new to Cacophony this semester and though I did browse through some previous posts – it was by no means an exhaustive search – so maybe this has been answered. And maybe I’m feeling a bit of what Sarah Ruth Jacobs described on this blog in 2011 as The Academic Crisis of Audience. But enough caveats here’s my question to you reader: who is the audience for this blog?

“Think! Think and wonder.

Wonder and think”.

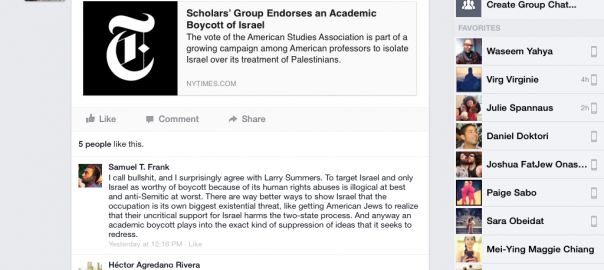

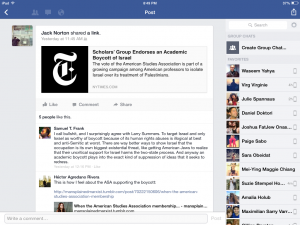

document, communicate, and represent their values and struggles. This article focuses on how San people used digital technologies to generate educational texts by transcribing and web publishing traditional oral folktales and to inject their own perspectives into critical political debates. In each of these cases digital media enabled San people to realize explicit and implicit social and political agendas that were realized through the use of digital media. This paper focuses on select digital representations of San people by San people and explores how these examples relate to larger issues of education and globalization in the region.

document, communicate, and represent their values and struggles. This article focuses on how San people used digital technologies to generate educational texts by transcribing and web publishing traditional oral folktales and to inject their own perspectives into critical political debates. In each of these cases digital media enabled San people to realize explicit and implicit social and political agendas that were realized through the use of digital media. This paper focuses on select digital representations of San people by San people and explores how these examples relate to larger issues of education and globalization in the region. caring while I worked on the final revisions just weeks after little bear joined us! And thank you little bear for loving your bouncy (most of the time) while I made the revisions too!

caring while I worked on the final revisions just weeks after little bear joined us! And thank you little bear for loving your bouncy (most of the time) while I made the revisions too!