Christopher M. Morrow

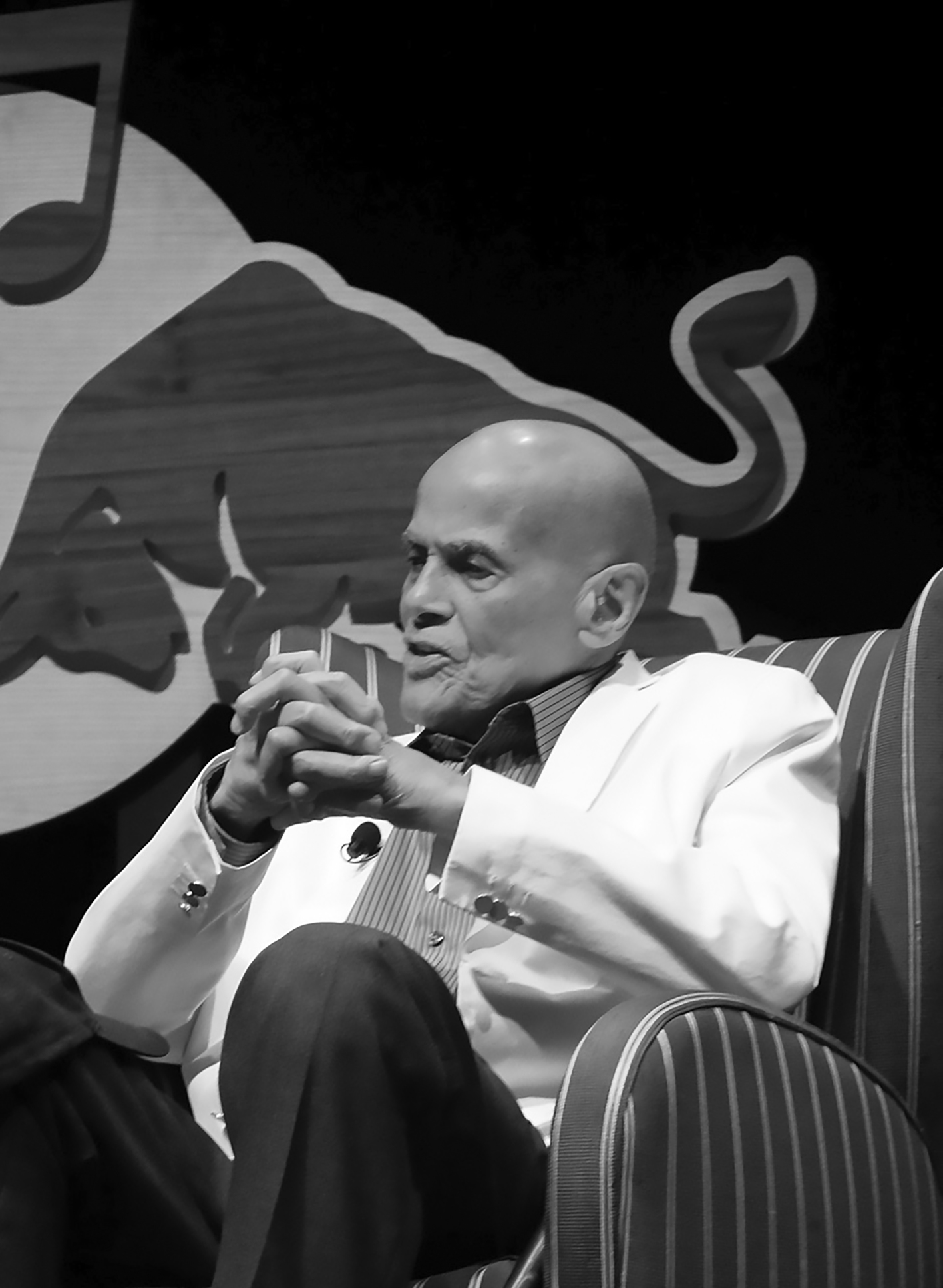

Bronx, New York-May 5:Actor/Human Rights Activist Harry Belafonte attends ‘A Conversation with Harry Belafonte’ presented by Jill Newman Production and Red Bull Music held at Hostos Community College on May 5, 2018 in the Bronx, New York City. (Photo by Terrence Jennings/terrencejennings.com)

On 5 May, the legendary performer and activist Harry Belafonte visited Hostos Community College for a conversation with Kimberly Drew, a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Drew introduced Belafonte to a standing ovation, to which he responded by waving in a humble exchange. Hostos Community College was an appropriate venue for the Harry Belafonte conversation. As an activist and artist, Belafonte had made it his life’s mission to advocate for the poor and the disenfranchised. From the onset of the evening, he spoke of his early commitment to resisting oppression for the Black community and highlighted the persistent problem of poverty in communities of color. Belafonte credited his working-class Jamaican mother for his value system and as inspiration for the development of his activist ideals. His commitment to social justice issues was born out of a lived experience in working-class communities in Jamaica and in the United States. “I have never understood the cruelty of the system,” he said “why people have to be poor.”

Belafonte identified first and foremost as an activist, and claimed to have stumbled upon art and music after he had already engaged in social activism. He used music as a platform to continue his activism, elevating him to a level of prestige both amongst musicians and with activist leaders such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. But his life story was not one of unhindered successes. Belafonte discussed how his activism cost him his livelihood, such as when many venues blacklisted him for the political content of his music. It also positioned him as a respected figure amongst civil rights leaders. “Being an activist a lot of people sought my services. Most notably Martin Luther King Jr., Paul Robeson and Malcolm X,” he said.

Belafonte spoke extensively about MLK, who was only 24 when they first met at the Abyssinian church in Harlem. He left a lifelong impression on Belafonte, who was only two years younger. Belafonte said he immediately committed to the civil rights movement after that first long conversation, and also recounted a nervous tic that had plagued MLK in his early years, which disappeared in time. “What happened to the tic, man?” Belafonte asked him during one of their many conversations to unfold over the years — to which MLK responded that it disappeared once he overcame his fear of death. This was a significant moment for Belafonte; it shifted his perspective on the interplay between life and death.

Drew prompted Belafonte to speak to the relationship between his activism and art, specifically focusing on his collaborations with Charles White. White was an African American Social Realist artist and a peer of Belafonte. Belafonte praised White in professional and personal terms and described him as “an enormous force in our community.” He encouraged the audience to visit White’s retrospective, which will be on display at MOMA beginning October 2018.

Drew prompted Belafonte to speak to the relationship between his activism and art, specifically focusing on his collaborations with Charles White. White was an African American Social Realist artist and a peer of Belafonte. Belafonte praised White in professional and personal terms and described him as “an enormous force in our community.” He encouraged the audience to visit White’s retrospective, which will be on display at MOMA beginning October 2018.

As the conversation transitioned to President Trump, Belafonte’s tone became more somber. Following his life’s engagement with activism and art, Trump’s politics manifested the most problematic aspects of American history. His concern was not that Trump exists, he said, but the level of support that elected him into office. The audience echoed his statement as they clapped and hummed in unison. “Donald Trump is not in my history. Not in my DNA” said Belafonte.

The evening concluded with a Q&A which drew two snaking lines on either side of the auditorium. Attendees included students, educators, artists, curators and fans of Belafonte. A music student and folk singer visiting from California asked about what attracted him to the folk form and song. “To me folk song carried information. Carried history.” Belafonte responded. He went on to sing a few bars from his classic, “Day O.”

Work all night on a drink of rum

Daylight come and me wan’ go home

Stack banana till de morning come

Daylight come and me wan’ go home

Come, Mister tally man, tally me banana

Daylight come and me wan’ go home

“Hearing him talk about his experience with Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, it was very inspiring” said Yarlyn Mercedes, African American studies major from Lehman College. Mercedes is one of many who attended the talk as a part of a Lehman College class on the African American Family. The students were accompanied by their professor, Dr. Mary Phillips, who enthusiastically advocated for students and youth learning from activists of previous eras. “Harry Belafonte is a living archive” said Dr. Phillips. When asked about the link between her course and the evening’s conversation, she said that “whenever we are talking about civil rights or poverty or mass incarceration, we are talking about families.” Dr. Phillips emphasized the importance of her students to be able to get a first-hand accounting of social historical events from Belafonte, and their implications on current events.

“Hearing him talk about his experience with Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, it was very inspiring” said Yarlyn Mercedes, African American studies major from Lehman College. Mercedes is one of many who attended the talk as a part of a Lehman College class on the African American Family. The students were accompanied by their professor, Dr. Mary Phillips, who enthusiastically advocated for students and youth learning from activists of previous eras. “Harry Belafonte is a living archive” said Dr. Phillips. When asked about the link between her course and the evening’s conversation, she said that “whenever we are talking about civil rights or poverty or mass incarceration, we are talking about families.” Dr. Phillips emphasized the importance of her students to be able to get a first-hand accounting of social historical events from Belafonte, and their implications on current events.

All proceeds from the event were directed to SANKOFA, a social action organization founded by Belafonte to match “high profile artists” with communities in activist and artistic collaborations. The term Sankofa is derived from West African mythology, explained Belafonte, and it is a metaphorical symbol used by the Akan people of Ghana – generally depicted as a bird with its head turned backward as if taking an egg from its back. It expresses the importance of reaching back to knowledge gained in the past and bringing it into the present in order to make positive progress.