JENNIFER POLISH

Last month’s Advocate editorial, “A New Feminism,” by Gordon Barnes, offers some excellent critiques of second-wave, White-dominated feminism as “a tool for reinforcing dominant ideologies and mores.” When critiquing Women’s History Month in the United States, the “equal rights” brand of feminism espoused by far too many, or the lack of critique of the military-industrial complex in films like 2012’s Invisible War, Barnes is absolutely spot-on – the liberal (as opposed to radical/intersectional) feminism espoused by (too often) White women like Emma Watson are generally hailed as progressive, but in fact shape anti-emancipatory attitudes. Indulging in a brand of feminism that, as Barnes writes, “cements the place of imperialist ventures” is indeed just that – at best, a cognitive dissonance-inducing indulgence, and at worst (and usually), a privilege.

Last month’s Advocate editorial, “A New Feminism,” by Gordon Barnes, offers some excellent critiques of second-wave, White-dominated feminism as “a tool for reinforcing dominant ideologies and mores.” When critiquing Women’s History Month in the United States, the “equal rights” brand of feminism espoused by far too many, or the lack of critique of the military-industrial complex in films like 2012’s Invisible War, Barnes is absolutely spot-on – the liberal (as opposed to radical/intersectional) feminism espoused by (too often) White women like Emma Watson are generally hailed as progressive, but in fact shape anti-emancipatory attitudes. Indulging in a brand of feminism that, as Barnes writes, “cements the place of imperialist ventures” is indeed just that – at best, a cognitive dissonance-inducing indulgence, and at worst (and usually), a privilege.

I will deploy the words that Barnes implied but did not explicitly use – the Whiteness of liberal feminism is overwhelming, and it is literally lethal for communities of color at home and abroad. Need I go further than, at the risk of enraging those who would #bottomforhillary, Hillary Clinton’s foreign policies and her “tough on crime” stance with Bill Clinton that fed mass incarceration?

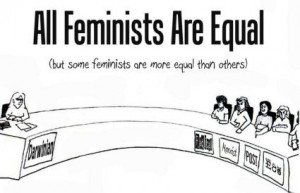

Throughout his editorial, Barnes is critiquing this lethal, liberal feminism. However, only using the word “feminism,” as he does, to describe this liberalism gives me pause. I would not be nearly as quick as Barnes to define liberal (read: White, middle class, citizenship-based, etcetera) feminism as just… feminism. While popular culture defines feminism as liberal feminism, to be sure – such is the privilege of dominant identities that they can remain unmentioned and invisible – for us to do so in our critiques of liberal feminism is to inadvertently reify the erasure of woman of color feminism that liberal feminism is already doing so well. Liberal feminists do not need our help, and I know it is not Barnes’ goal to help them.

To that end, it is important to avoid dismissing all feminism as anti-emancipation when we really mean that liberal feminism is anti-emancipation. I, too, aesthetically enjoy “liberation” as a rhetorical tool, but I worry that often, people read calls for “something greater than feminist ‘equality’” out of context and hijack these statements for the purpose of arguing that women have ‘come far enough. Because look, there’s a woman CEO!’.

Yes, liberal feminism is about supporting anti-immigrant “nation-building,” Islamophobic and racist wars to “protect” women in Afghanistan, and community-destroying “war on drugs” policies, all in the name of “(White) womanhood.” Just as Barnes argues, these neoliberal goals are not about liberation. Liberal feminism cannot be about liberation for anyone because it is based in a fundamental essentialism which ignores the myriad ways that women are not, and never have been nor will be, a monolith.

Race, class, ability, migrant status, region, sexuality, gender, body type – and on and on – all separate women from each other and give us dramatically different experiences. For example, issues of justice that women with dis/abilities encounter are usually overlooked by groups of women without those particular dis/abilities. Remember here, of course, that dis/abilities affect people differently based on dis/ability type, as well as the person’s race, class, migrant status…the ever important but also ever frustrating identity/privilege list again! Barnes is right to highlight the ways that liberal feminism actively distances itself from all of these active intersections, eliding differences amongst women by issuing bland claims for “equality” that – in such a misogynist society – we often feel as though we have no choice but to applaud, because at least someone is saying…something. But that “something” is not about liberation.

Weaving a definition of feminism that refuses to elide the massively important activisms, writings, and lives of radical woman of color feminists, however, does have the potential to create a definition of feminism that can be about the liberation that Barnes gestures toward.

This liberation cannot be achieved, however, if issues of transgender liberation are discussed in ways that harm transgender individuals and communities. Barnes clearly has excellent intentions when he integrates the concerns of transphobic and misogynist violence aimed at trans women into his critique of feminism, but he does so in a way that inadvertently conflates sex and gender.

When discussing former Navy SEAL Kristen Beck, Barnes is absolutely right to criticize the CNN documentary Lady Valor for uncritically featuring “Beck coldly discuss[ing] killing Afghanis and Iraqis.” This glorification of US imperialist violence is, unfortunately, something that is familiar to mainstream LGBT audiences (especially those who fought for the repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell).

However, in the midst of this exigent critique, Barnes parenthetically notes that Kristen Beck was “previously known as Christopher.” Beck’s assigned name is simply not relevant, and the voyeuristic, invasive question of “what did your name used to be?” that out trans people have to contend with daily – which Barnes unfortunately answers here without being asked – does not belong in a liberationist discourse.

Relatedly, Barnes inadvertently upholds the essentialist notion that trans identity is affirmed or denied by medical transition. Using the phrase “sexual/gender transition” to describe Beck’s coming out as a woman instead of “gender transition” is unsettling in its simultaneous differentiation and equation of sex and gender. This vaguely positions sex as a ‘biological reality’ as opposed to the social constructedness of gender. This is especially amiss in light of the fact that earlier in the piece, Barnes states that, “gender parity is a different problem” than “social parity between the sexes.”

Ironically, in other contexts, trans and woman of color feminisms often unite in their anti-essentialist strivings toward the liberation that Barnes is trying to advocate for. Trans feminisms often further the feminist task of revealing gender as a socially constructed product of power relations in this society – trans feminisms often extend this to essentialist notions of “sex,” revealing that “biological sex,” too, is a product of societal power relations. Woman of color feminisms, similarly, are anti-essentialist in their insistence that White womanhood does not define all women. These feminisms converge in that they both trouble the very grounds upon which any universalist ideal of “womanhood” plants its proverbial feet – perhaps this refusal to universalize experiences is where a liberationist politics can begin to take shape.