By Anne Donlon

Commonly, we hear of figures in the 1930s and early 1940s who may have been involved in John Reed Clubs, radical newspapers, writers congresses, and communist-affiliated organizations, but later in the forties and fifties, broke with the Communism, denounced its politics, or took efforts to publicly distance themselves from the Party. Versions of this narrative attend the biographies of Ralph Ellison, Richard Wright, Claude McKay, and Langston Hughes. The cartoonist Ollie Harrington was different. Indeed, as Brian Dolinar observes in Black Cultural Front: Black Writers and Artists of the Depression Generation, “Different from the experiences of other black writers and artists who broke with the Communist Party, Harrington moved closer to the Left in the postwar years.”

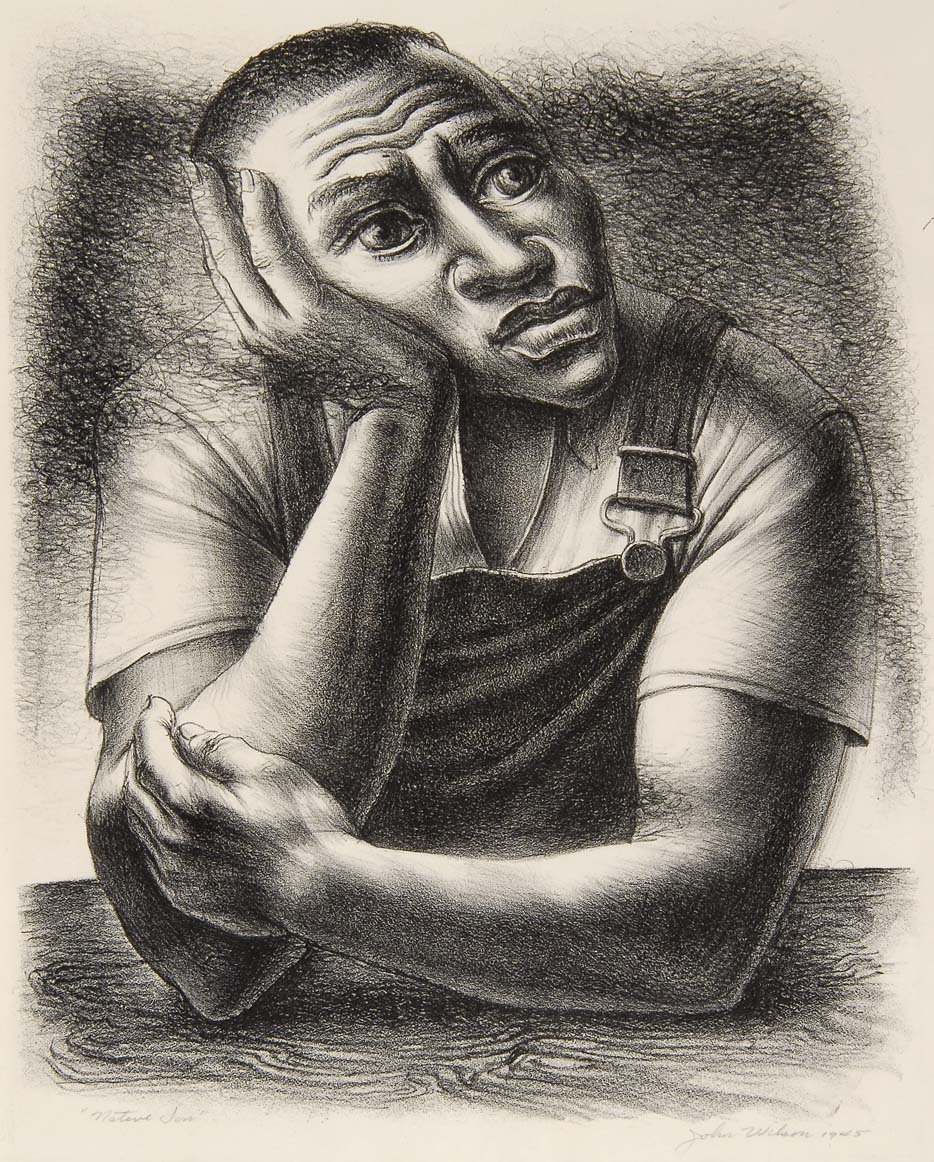

Ollie Harrington began drawing cartoons for newspapers as an art student in the 1930s, and after World War II became politically active working on public relations for the NAACP in its various campaigns. He went on to be much more involved on the Left, however, traveling to the Soviet Union, and living in East Berlin from 1961 until his death in 1995. In the 1930s, before going to the Yale School of Fine Arts, Harrington published cartoons in the National News and the Amsterdam News. He was working for the latter when the paper fired several writers, and workers went on strike for eleven weeks and organized a boycott. When the strike was settled, Harrington returned with the “Dark Laughter” cartoon series that featured the character “Bootsie” that he continued to draw over the next several decades. “Bootsie” became a popular culture touchstone.

Within a few years, his cartoons were picked up by the Pittsburgh Courier, a black weekly newspaper with a sizeable circulation. Harrington syndicated his cartoons to many publications, and he joined Adam Clayton Powell Jr.’s newspaper The People’s Voice in 1942. During World War II, he traveled to Europe to cover the war, among the first African American journalists the United States War Department allowed to cover a war. Harrington’s political commitment markedly increased after World War II, when he worked for the NAACP on a campaign for justice in the face of racialized violence in Columbia, Tennessee and Monroe, Georgia in 1946. In the same year, he worked for justice for Isaac Woodward, a black veteran who was beaten and made blind while traveling through South Carolina in uniform.

It was during this that Harrington’s Bootsie cartoons became more politicized. Soon after, Harrington split with the NAACP and became more active on the Left. He was involved in Labor Party campaigns, did public relations for the Communist candidate Ben Davis’s bid for a seat on the City Council in New York, and chaired a committee to elect W. E. B. Du Bois to the Senate. He worked for Paul Robeson’s newspaper Freedom in the late 1950s, and contributed to many campaigns to defend people against anticommunist persecution. Harrington eventually moved to Europe to escape the political climate in the United States., living out the remainder of his life in East Berlin.

Brian Dolinar’s book devotes one of its chapters to Harrington, and argues that though Harrington was a prominent popular artist of the time, his association with communism led to his subsequent obscurity. Dolinar is interested in recovering such figures and histories. Focusing on the impact of the National Negro Congresses and the work of Langston Hughes, Chester Himes, and Ollie Harrington, Dolinar points out the many ways that politics fostered in the 1930s continued to inform the politics and art throughout later decades. In his chapter on the National Negro Congress, for example, Dolinar describes the interconnected organizing networks that brought artists and writers together, and introduces a cast of characters that recur throughout the remainder of the book. The section on Hughes links his newspaper reporting in the Spanish Civil War to the “Simple” stories he published in the Chicago Defender in the following decades. Jesse B. Semple’s observations in the later stories often present political views continuous with his views in the 1930s, including critiques of the anti-communist efforts of the state. The chapter on Chester Himes points out the connections between his experience and writing during the Works Project Administration era, and the detective fiction Himes wrote in the following decades.

Langston Hughes scholarship is somewhat haunted by his testimony at the House of Un-American Activities Committee, where he infamously denied affiliation with the Communist Party. Dolinar provides a more complex picture than the public testimony presents. Looking at transcripts from the private questioning conducted by Roy Cohn two days previous to the public hearing, Dolinar points out the contrast between the charged private testimony—in which Hughes stated there was a time he desired a Soviet form of government and coyly responded to Cohn’s queries about other Party members that he’d never seen anyone’s party cards—and the more subdued tone of the public hearing. Dolinar argues that Hughes’s performance in the public hearing shouldn’t be seen as a “retreat from politics,” but rather a strategy of survival. Hughes continued to be outspoken and critical after the hearing. Dolinar also notes that the literary works that concerned the committee were not only the radical poems of the 1930s, but also recently published Simple stories including “Something to Lean On,” and “When A Man Sees Red,” in which Simple stands up to his boss and says, “In my opinion, a man can be black or red—or any color except yellow. And I would be yellow if I did not stand up for my rights.”

Dolinar also sets out to rescue novelist Chester Himes’s engagement on the Left and reinsert it into scholarly conversations on Himes. Himes first published prison stories in Abbott’s Monthly and Esquire as an inmate in the 1930s, and, after he was released in 1936, he eventually found work with the WPA. Working at the Cleveland Public Library, he met Jo Sinclair, the pen name of the lesbian Jewish writer Ruth Seid, who based a character on Himes in her unpublished work of fiction, “They Gave Us a Job.” Himes went on to write for the Ohio Writer’s Project, and connected with the Karamu House in Cleveland. At Karamu House he met Langston Hughes, and made connections that eventually led him to Hollywood. The geography of this chapter shifts the hubs of black literary activity from Harlem and Howard to Cleveland and California. Himes, like Harrington, Richard Wright, and others, eventually emigrated to Europe to escape the racism and political suppression of the United States.

Dolinar’s work is strongest in his narration of the detailed histories surrounding these figures. His account of Hughes in the Spanish Civil War is well-researched, providing a meticulous account of Hughes’s activity in Spain, his activism on behalf of Spain in the UnitedStates, and the cast of characters Hughes interacted with during that period of his life. Dolinar provides thorough accounts of the National Negro Congresses and the efforts that grew out of them, including performances, rallies, and the George Washington Carver School in Harlem, a “people’s institute” where the artist Elizabeth Catlett taught a class on “How to Make a Dress” and Gwendolyn Bennett taught a class on black history. The book’s storytelling is gripping, and Dolinar makes a particular effort to point out the crossings of his main players: Hughes meets Himes at Karamu; Himes and Harrington attended an “international party” hosted by Hughes in 1944; Hughes compares his Simple character to Harrington’s Bootsie when proposing Harrington as an illustrator for a book project (though the collaboration didn’t come to fruition).

Black Cultural Front’s organizational strategy emphasizes individual figures, though certain networks and infrastructures clearly emerge as crucial. The chapter on the National Negro Congress underlines one key organizing hub that brought a wide range of artists, activists, and writers into contact. In the chapters on Hughes, Himes, and Harrington that follow, although individuals take the forefront, infrastructures like the black press, especially its weekly newspapers, institutions like Karamu House, and the Works Project Administration play key roles in creating threads that run through these individuals’ lives. Dolinar’s overall project might have benefited from the addition of a few explanatory remarks on the logic of the book’s organizing framework, and on the importance of certain trends that appear within the latter chapters without structural highlighting. For instance, while the presence and contributions of women like Gwendolyn Bennett, Marvel Cooke, Jo Sinclair, and Esther Cooper Jackson emerge, and the international aspects of these networks are noted, the book’s organization doesn’t particularly highlight them. Even the role of black newspapers, whose centrality is clear, is not particularly announced. The history Dolinar presents is rich and textured, and one can imagine future projects that take up some of the themes that go unremarked, or are mentioned in passing, such as the importance of children’s book projects in this period.

Black Cultural Front aims to make a historiographic intervention. Black Cultural Front’s title alludes to Michael Denning’s groundbreaking Cultural Front: The Laboring of Twentieth-Century American Literature (1996), a book that describes various and interconnected artistic projects on the Left. For Denning, the “cultural front” is largely mapped onto the Popular Front, and the book focuses almost exclusively on the culture of the 1930s and early 1940s. For Denning, despite the fact that “the Popular Front was defeated,” the work of the cultural front lived on to have a “profound impact on American culture, informing the life-work of two generations of artists and intellectuals.” In distinction, for Dolinar, the cultural front itself existed into the McCarthy era. He speaks of “those who were still a part of the black cultural front” in the late 1950s. And, Dolinar writes, “it was the atmosphere of McCarthyism that put a strain on relationships and eventually led to the break-up of the black cultural front.” Thus, he states in the introduction, “I will avoid referring to black cultural radicalism in terms of the Popular Front, the period of 1935-1939 that Denning says best characterizes the coalitional politics that attracted artists and writers to the Left. Such a framework, I would argue, is too narrow to understand this phenomenon.”

Dolinar’s intervention, then, is to describe a cultural front concerned with antiracist activity, enlivened by African American players, that was not defeated with the Popular Front, and that did not give up the fight against fascism at home. The black cultural front Dolinar describes survived into the late 1950s and 1960s. In the Cultural Front’s focus on the age of the C.I.O., May 1or International Workers’ Day is a touchstone date. In the Black Cultural Front, February 14 is the commemorative date that comes up again and again. Frederick Douglass’s birthday was the day of the 1936 National Negro Congress, the second day of the first Southern Negro Youth Congress in 1937, and the day that the first issue of the People’s Voice came out in 1942. February 14 was also Ollie Harrington’s birthday, which informed the date of the February 10, 2007 “sketch in” of black cartoonists, discussed in Dolinar’s conclusion. In the final pages of the book, Dolinar gestures towards connections between the black cultural front and the contemporary moment, citing Walter Mosley’s Easy Rawlins series of detective novels, set during the Cold War, and his “Tempest Tales,” modeled on Hughes’s Simple stories, and Aaron McGruder’s Boondocks cartoon series, “one of only a small handful of black cartoons in syndication since the days of Ollie Harrington and the black press.”

In taking a holistic view of the middle decades of the twentieth-century, Dolinar’s text joins several scholarly works that link Popular Front and post-war literary culture. Recent literary studies like Alan Wald’s Trinity of Passion: Anti-Fascism and the Literary Left; James Smethurst’s The Black Arts Movement: Literary Nationalism in the 1960s and 1970s; Lawrence Jackson’s The Indignant Generation:A Narrative History of African American Writers and Critics, 1934-1960; and articles like Smethurst’s “‘Don’t Say Goodbye to the Porkpie Hat:’ Langston Hughes, the Left, and the Black Arts Movement”; and Frederick Griffiths’s “Ralph Ellison, Richard Wright, and Angelo Herndon” have highlighted the impact of 1930s left culture on literature in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. Similarly, historians speak of a long civil rights movement, linking struggles in the 1930s directly with the period more commonly referred to as the civil rights era. Dolinar contributes a level of historical detail in the accounts of these lives and cultural networks, in particular in the recovery of Ollie Harrington. Black Cultural Front fills in some of the interpersonal and intertextual genealogies of black cultural work in the United States, and attempts to shift the narration of these lives from before and after Communism to an understanding of a continuous movement that had a dynamic relationship to a variety of political climates.